Bruce McLaren, Grand Prix racer and founder of the McLaren F1 team, entered his first competition in 1952, in a Seven Ulster restored by his father.

And Arthur Mallock, father of the eponymous Mallock U2 racers that still dominate club events today, developed all the chassis systems he was renowned for around his ‘Bombsk’ special, based on a short-chassis Austin Seven.

But today we’re not driving anything so glamorous.

The British Motor Museum in Gaydon has a fine and diverse collection of Sevens, and has been kind enough to let us sample two versions that bookend the model’s long production run: a 1923 Chummy tourer, and a very late 1938 Ruby saloon.

A three-synchromesh gearbox plus a revised chassis contribute to an easier driving experience in post-1934 Austin Seven Ruby models

Contrasts don’t come much greater.

First up is the Chummy, which in 1923 would have been the only version available and is closest to Austin and Edge’s original design.

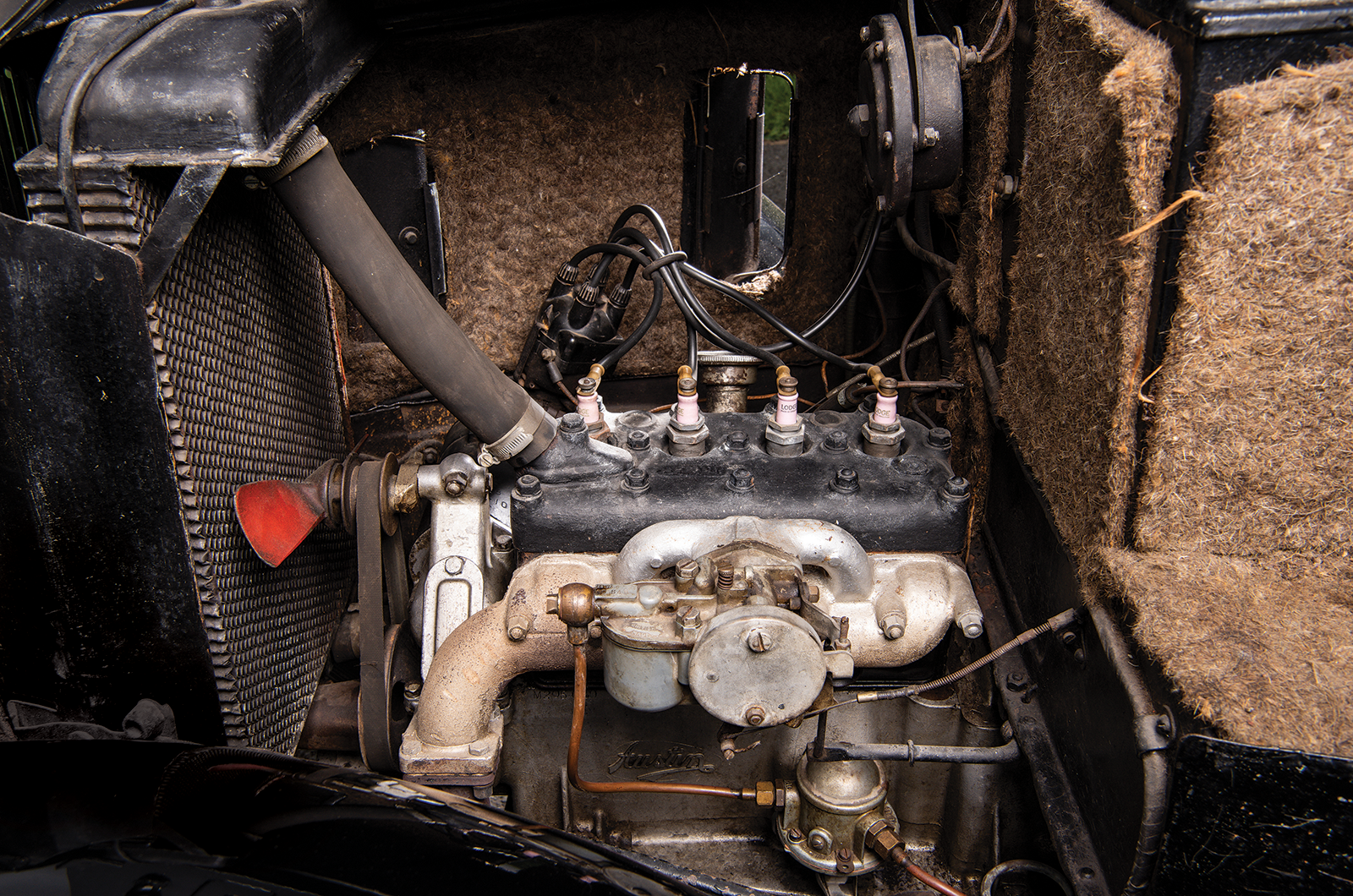

With carburettor primed (only necessary because the engine is cold), magneto switched to ‘on’ and the hub-mounted ignition lever on the four-spoke steering wheel in its fully retarded position (to avoid injury when the engine fires), you engage a little handle with the crank via a hole below the radiator and it fires on the first rotation.

Back in the cabin, and my 5ft 7in frame fits perfectly into the small driver’s bucket seat.

The Ruby’s well-stocked dashboard

In front of me is… well, not much. One dial for amperes and some light switches.

The Seven was the first mainstream car to have its pedals arranged in the way we’re familiar with today, as opposed to using the central throttle favoured by most contemporaries.

Using the accelerator is more like pressing a button, and the clutch has an equally short travel – it’s very abrupt, too.

But this century-old car feels remarkably sprightly. Not fast, by any means, but nippy, biddable and eager to please.

The Austin Seven Ruby has a richer cabin with more space

The three-speed gearshift has a well-oiled feel to it, and works in a reverse H-pattern, with first to the right and back, and second across to the left and forward (reverse is opposite first, with a tab to prevent accidental selection).

This early car responds well to a polite double-declutch, but you need to use generous revs in second to cater for the wide gap to top. Then it’s plain sailing.

Steering is very direct and light as soon as you’re up to speed, but the car’s lack of dampers means that, even at 35-40mph, it’s easy to be deflected from your course on anything other than smooth road surfaces.

Later cars are fitted with a four-speed ’box

The little engine is torquey rather than revvy, and chunters along quite happily at moderate speeds, which, given the braking performance, is all you would want to consider: there may be four of them, but slowing this tiny car is a leisurely pursuit.

In comparison, the Ruby feels positively luxurious.

Four dials face you in a neat black binnacle, with a starter key and ignition advance now managed by a conventional distributor.

Pull away and everything is more convenient: the four-speed ’box uses a modern shift pattern, working from left to right, and the clutch has a longer, more progressive action.

The interior of the Austin Seven Ruby is considerably more plush than the earlier Chummy

The Ruby is far more refined, too, losing the first-gear whine of the Chummy, and by the time we’re motoring along at 40mph (50mph would be about its lot) the whole car feels very civilised.

But as fun as the Chummy? Strangely, no.

The steering is vague, and the car wanders over the slightest of road cambers, meaning plenty of concentration is required.

In fairness, this could be down to a lack of use (this was its first outing for some time) but, even so, it’s the Chummy that steals your heart.

‘In comparison with the Chummy the Ruby feels positively luxurious; pull away and everything is more convenient’

Sir Herbert Austin took a personal commission of two guineas (£2 10s) for every Seven sold, which, given that nearly 300,000 of them were built, is quite some return.

But he also democratised motoring for the masses by licencing the Seven around the world, and for that the price was pitifully small.

Images: Stuart Collins

Thanks to: Stephen Laing at the British Motor Museum; Nick Turley at the Austin Seven Clubs’ Association

Simplicity with innovation

The Austin Seven’s four-wheel braking was an innovation

On any Austin Seven, you will find a plate in the cabin listing up to 23 patents held by the model, but three stand out.

While the Seven was the first truly mainstream car to employ four-wheel braking, the system had been conceived before.

However, Austin’s unique take meant that the Seven’s rear axle was braked in the normal way by the foot pedal, but the front brakes were activated by the hand lever, or parking brake, simplifying what would otherwise have been a very complicated system.

The idea of patenting ‘detachable wheels’ appeared laughable, but three drum-mounted pegs meant that removing the Seven’s wheelnuts was unnecessary: you just loosened them, rotated the wheel to the left slightly and lifted it off, with the nuts passing through oversized holes.

Austin patented ‘detachable wheels’ which were easily removable

But it was the Seven’s ingenious chassis design that set it apart and above many more expensive cars.

The steel frame was A-shaped, with the apex of the ‘A’ forming a mounting for the front transverse leaf spring, connected by radius arms and balljoints on either side.

It was light, stiff, and simpler and cheaper to produce than a more common H-frame chassis, while offering drivers a level of agility previously unheard of in such a low-priced car.

Sevens by another name

The Dixi DA1

Enterprising as ever, Sir Herbert Austin never missed a trick when it came to maximising the profit potential of the Seven.

In 1923, he granted a licence to Automobiles L Rosengart in France to build the Seven.

Known as the Rosengart LR2 and on sale from 1928, it was well promoted (one car covered 100,000km in a three-and-a-half-month road trip to prove its durability) and sold in various forms until 1939.

Sevens even emerged in the USA, when a licence to assemble the car – known there as the Bantam – was granted in 1929.

Unfortunately, sales dropped severely in the wake of the Great Depression and the American Austin Car Company filed for bankruptcy in 1934.

The DA1 gained a BMW badge after the brand purchased Dixi in 1928

No licences were granted in Australia, but coachbuilders imported rolling chassis to produce their own derivatives, of which Holden’s mid-’20s tourers and roadsters were the most prolific.

And there’s still debate about whether a licence was ever granted to Datsun for its 1932 Type 11, which bore an uncanny resemblance.

But perhaps the best-known licenced Seven is the Dixi. In 1926, Fahrzeugfabrik Eisenach (Dixi-Werke) signed up to build the Austin in Germany, and the first Dixi DA1 was produced in 1927.

The following year, the business was purchased by BMW and the Dixi continued to be built and developed until 1932, with 25,300 units produced.

The 1931 Dixi pictured above was gifted by BMW to the British Motor Industry Heritage Trust in ’94 to celebrate its then-new partnership with Rover.

Continuing a century on the track

The Speedex racer is simple and fun © Richard Styles

I doubt another car in history has influenced motorsport as much as the Seven. Yet the little Austin was never designed to be a racing car, nor even a sports car.

When it made its debut 100 years ago, it was billed as a small and affordable family car for the masses.

The Seven was raced comprehensively and successfully during the ’20s, setting records at Brooklands to keep the car in the news, and Twin Cam single-seaters were winning races until production finished in 1939.

But it was in the late 1940s that the Seven really took on a racing life. A 750 Formula was created in 1949, with Sevens as the key donors, and it is now the longest continually running race series in the world.

Specials were fast and fun when near standard, but when highly modified they became the primary way to win in the burgeoning club-racing scene.

Those who competed comprise a Who’s Who of motorsport: as well as Arthur Mallock, Bruce McLaren and Colin Chapman, Mike Costin, Eric Broadley and John Cooper all raced Sevens.

Even Gordon Murray’s first race car was made to the 750 Formula.

As part of the Seven’s centenary celebrations, the 750 Motor Club invited me to Snetterton in July to race two cars in the Historic 750 Formula Series, which is primarily for Austin-based machines.

The first is a Speedex, built by the firm founded by Jem Marsh, raced by Linda Price in the non-supercharged class.

It’s a pretty conventional Special, with a 747cc engine and the four-speed ’box that was standard on post-1932 cars.

As I squeeze in, the car immediately feels kart-like: compact, upright, knees bent, snug.

Before the event, I’d been telling myself that this is an 88-year-old car so I must be ginger with it. But you wouldn’t know that the engine is so small or so old, because it pulls cleanly and linearly to the far side of 6000rpm.

This fabulous supercharged racer was developed by legendary test driver John Miles © Richard Styles

The steering is direct, quick and takes on lots of weight very rapidly. Even on skinny old tyres, there’s more grip than power.

These are privately owned cars with open wheels, driven by club drivers in the friendliest paddock I’ve visited, so the racing is extremely respectful.

Then there’s the blue car. John Miles was a Formula One driver, Lotus test/development driver and engineer and, for a time, an Autocar writer, and this was the fourth Seven he owned after his retirement.

Having set out to make the fastest Austin he could, he offset the drivetrain to create space to sit low between it and a chassis rail, rather than on the chassis, and semi-stressed the gorgeous aluminium body to increase rigidity.

He found the car a home in the 750 championship, and it competes in the supercharged category today.

Its current owner, automotive engineer Tim Roebuck, tells me that it has 80bhp, will rev to nearly 7000rpm and weighs just 325kg.

It’s a joy, with an engine that gets going early and keeps pulling. The steering is light and accurate, and the car is fast: at Snetterton it will average more than 65mph in Roebuck’s hands.

This race is a handicap, where we set off at predetermined intervals with the intent that we all finish at the same time.

Not that the result is the takeaway, anyway. This is a celebratory series, not a cut-throat championship. As one participant explains to his friends: you do a bit of racing, sit and drink tea and eat cake together, then race again.

In what is one of my favourite books, Building and Racing my ‘750’, author PJ Stephens shares stories from the paddock of when competitors helped each other make it to the grid.

A century after the Seven’s introduction, this club and the mighty, tiny Austin are still pulling people into the sport.

Words: Matt Prior

Images: Richard Styles

Factfile

Austin Seven (1923 Chummy)

- Sold/number built 1922-’39/290,924

- Construction steel A-frame chassis, separate steel body

- Engine iron block and head, aluminium crankcase 747cc ‘four’, Zenith carburettor

- Max power 10.5bhp @ 2400rpm

- Max torque n/a

- Transmission three-speed manual, RWD

- Suspension: front forged axle, leading arms, transverse leaf spring rear torque tube, live axle, quarter-elliptic leaf springs

- Steering worm and roller

- Brakes cable drums

- Length 9ft 2in (2794mm)

- Width 3ft 10in (1168mm)

- Height 4ft 10in (1475mm)

- Wheelbase 6ft 3in (1905mm)

- Weight 840lb (381kg)

- 0-60mph n/a

- Top speed 50mph

- Mpg 42

- Price new £165 (1923)

- Price now £8-20,000*

*Prices correct at date of original publication

READ MORE

100 years of the Austin Seven

Dressed to deceive: Rosengart SuperSept

The race to 100mph: MG C-type Montlhéry Midget vs Austin Seven Ulster TT

Simon Hucknall

Simon Hucknall is a senior contributor to Classic & Sports Car