-

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car -

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

© Olgun Kordal/Max Edleston/Classic & Sports Car

-

Motoring milestones

In the pantheon of motoring endeavour, a sporting vehicle’s maximum speed has arguably held greater sway in manufacturers’ marketing departments than any other performance metric.

It may be less relevant now, when even the lowliest city car can comfortably exceed the national speed limit, but for most performance-car makers a high top speed remains a badge of honour – even if experiencing it properly nowadays means a visit to a German autobahn or Australia’s Northern Territory (or your local prison cell, if you’re particularly foolhardy).

The 10 road cars described on the following slides, decade by decade, have been the fastest of their kind officially sold in the UK across the past 100 years.

-

Trailblazers

They’re important because their envelope-pushing Vmaxes have been achieved despite all the compromises wrought by having to make a car compliant for everyday use on the public road.

Yes, top speed has been their collective stock-in-trade, but in each case it has also meant the cars were safer, stronger, aerodynamically more efficient and stopped/handled with greater aplomb than less ambitious machines.

In other words, they are pinnacle cars that improved the breed overall.

That this will be the last time we can put together such a set of cars is poignant, too.

-

Internal-combustion celebration

Which means that this is also a final celebration of the mighty internal-combustion engine, in all its myriad guises, from four to 16 cylinders.

It has powered the automotive world for the past 130 years, so it’s only right and proper that we showcase its meteoric rise in power, durability and efficiency before it’s outlawed from new cars completely.

So for now, fasten your seatbelts as we accelerate through 200 miles per hour in 100 years.

Thanks to: Everyman Racing for the use of its Prestwold test track (everymanracing.co.uk)

-

1920s: Vauxhall 30-98 OE-type

Top speed: 100.7mph

A century ago, the very idea of a production car achieving 100mph would have been eulogised by schoolkids and automobile makers alike.

Competition cars had plied their ton-up wares at tracks such as Brooklands since the Edwardian era, but they were pared-down beasts making no concessions to road use.

Replicating such high speeds in a car wearing numberplates and full bodywork would be quite another thing.

Vauxhall was a company at the forefront of performance engineering, its C-10 Prince Henry model of 1911 already acknowledged as the first true production sports car.

And it was because of that reputation that businessman Joseph Higginson approached company seniors in late 1912, asking them to build an unbeatable roadgoing car to compete in hillclimbs.

-

1920s: Vauxhall 30-98 OE-type (cont.)

Using a development of the A10 engine, famed Vauxhall technical director Laurence Pomeroy created a car with the lightest-possible running gear and bodywork.

Known as the 30-98 E-type and rated at 85mph – an extraordinary speed, pre-WW1 – the car was delivered to Higginson in 1913, and soon afterwards he set a 55.2 secs time at Shelsley Walsh, a record that stood for eight years.

The potential for still more performance was evident, though.

Pomeroy’s post-war successor at Vauxhall, CE King, was soon to develop an overhead-valve pushrod engine for the 30-98, reducing its capacity by 301cc to 4224cc, but increasing power from 98 to 115bhp.

-

1920s: Vauxhall 30-98 OE-type (cont.)

The origins of the model’s name are always debated, with both its initial output and bore size being 98bhp and 98mm respectively.

However, the Vauxhall-published book Vauxhall 1857-1946 suggests ‘30’ was for the projected bhp at 1000rpm, and ‘98’ for the original output, the name retained even after it increased.

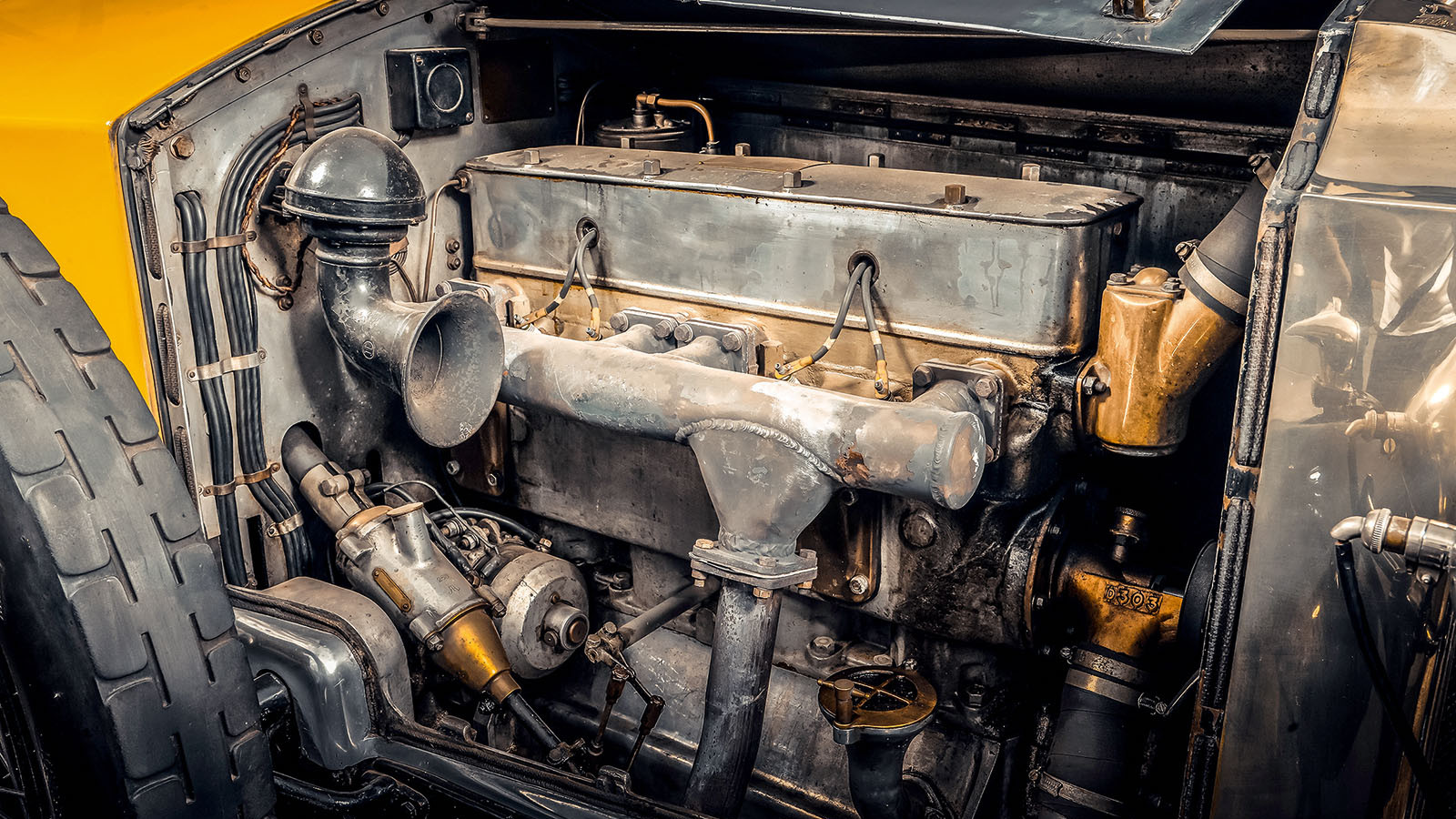

Based on the E-type engine’s sturdy bottom end, the OE’s revised four-cylinder block afforded overhead valves so large that they needed rockers on offset pedestals.

And with 3400rpm now achievable in the car’s upper reaches, double valve springs and substantial four-bolt Duralumin connecting rods were essential.

Transmission was, as before, via Vauxhall’s own four-speed, D-type-derived gearbox and multi-plate clutch.

-

1920s: Vauxhall 30-98 OE-type (cont.)

Advertised as ‘The Car of Grace That Sets the Pace’, the OE-type immediately struck a chord with well-to-do enthusiast drivers who were keen to push the high-speed envelope to its outer edges.

However, one Major L Ropner clearly wanted more.

In a letter to The Autocar’s editor, he complained of being unable to buy a road car capable of covering the flying mile at more than 100mph.

Gauntlet laid, Vauxhall promised Ropner that the 30-98 could achieve this, and invited him to Brooklands to see the factory’s test driver, Matt Park, exceed the ton in the very car that he’d ordered.

That 30-98, in road specification with full mudguards, blade wings and spare wheels in place (but with two aeroscreens replacing the upright full windscreen, plus a cowled radiator) clipped 100.7mph that day.

-

1920s: Vauxhall 30-98 OE-type (cont.)

It was the first production car sold in Britain to be officially recognised with a 100mph top speed.

Representing the model today is OE268, a 1926 OE-type with a standard factory Velox body, which has been borrowed from Vauxhall Motors’ Heritage Collection.

Arguably one of the most original of the near-200 30-98s that survive from a total E/OE production of 598, it has the kind of patina you’d expect from decades spent promoting the company’s history after it was bequeathed to Vauxhall in 1947.

With a centre throttle, a reverse H-pattern gearshift next to your right knee and an outboard brake lever, the 30-98 is not a car you can jump into and drive easily on first acquaintance.

With the Autovac’s brass lever pulled down, Zenith carb tickled and ignition fully retarded, the ‘Thirsty’ fires on first turn.

-

1920s: Vauxhall 30-98 OE-type (cont.)

You hear each and every revolution of its four 1056cc cylinders as you peer down the long, fluted bonnet towards the large Griffin mascot atop the radiator.

Press down on the heavy clutch then push the gearlever right and forwards, and you’re in business.

Changes need a confident hand and a sympathetic ear to contend with the weighty flywheel and lack of synchromesh but, once in top, ample torque hauls the 3800lb Vauxhall through every bend on our track with ease.

The 30-98 proves to be frighteningly quick, and surprisingly deft-handling for one so old.

-

1920s: Vauxhall 30-98 OE-type (cont.)

It’s physical to steer, but grip is excellent and you find yourself taking liberties you didn’t quite expect through the faster bends.

But this is a vintage Vauxhall, so braking (from the hand lever; the foot pedal is a dual-purpose front-wheel and prop brake best left for emergency stops) is not for the faint-hearted.

Spirited driving on the road would require the odd downchange to help slow the car, which means your right hand alternating between gear and brake levers to avoid contact with the scenery.

But what a way to start our high-speed journey!

Thanks to: Vauxhall Motors (vauxhall.co.uk); British Motor Museum (britishmotormuseum.co.uk)

-

1920s: Vauxhall 30-98 OE-type (cont.)

Factfile

Sold/number built 1923-’27/312

Engine all-iron, ohv 4224cc ‘four’, with Autovac and Zenith 48RA carburettor

Max power 115bhp @ 3400rpm

Max torque 175lb ft @ 3400rpm

Transmission four-speed manual, RWD

Suspension: front semi-elliptic leaf springs, Hartford friction dampers rear live axle

Steering worm and wheel

Brakes mechanical drums f/r

Weight 3803lb (1725kg, as tested with factory Velox body)

0-60mph 17 secs

Top speed 100.7mph (with aeroscreen and cowled radiator)

Price new £1020 (1923, rolling chassis) -

1930s: Bentley 8 Litre

Top speed: 107.3mph

Establishing the top speeds of pre-war cars is a fraught business that not only requires a solid and incontestable baseline for each nominee, but also an awareness that very few cars from high-end marques would look or perform in the same way after they left their respective factories.

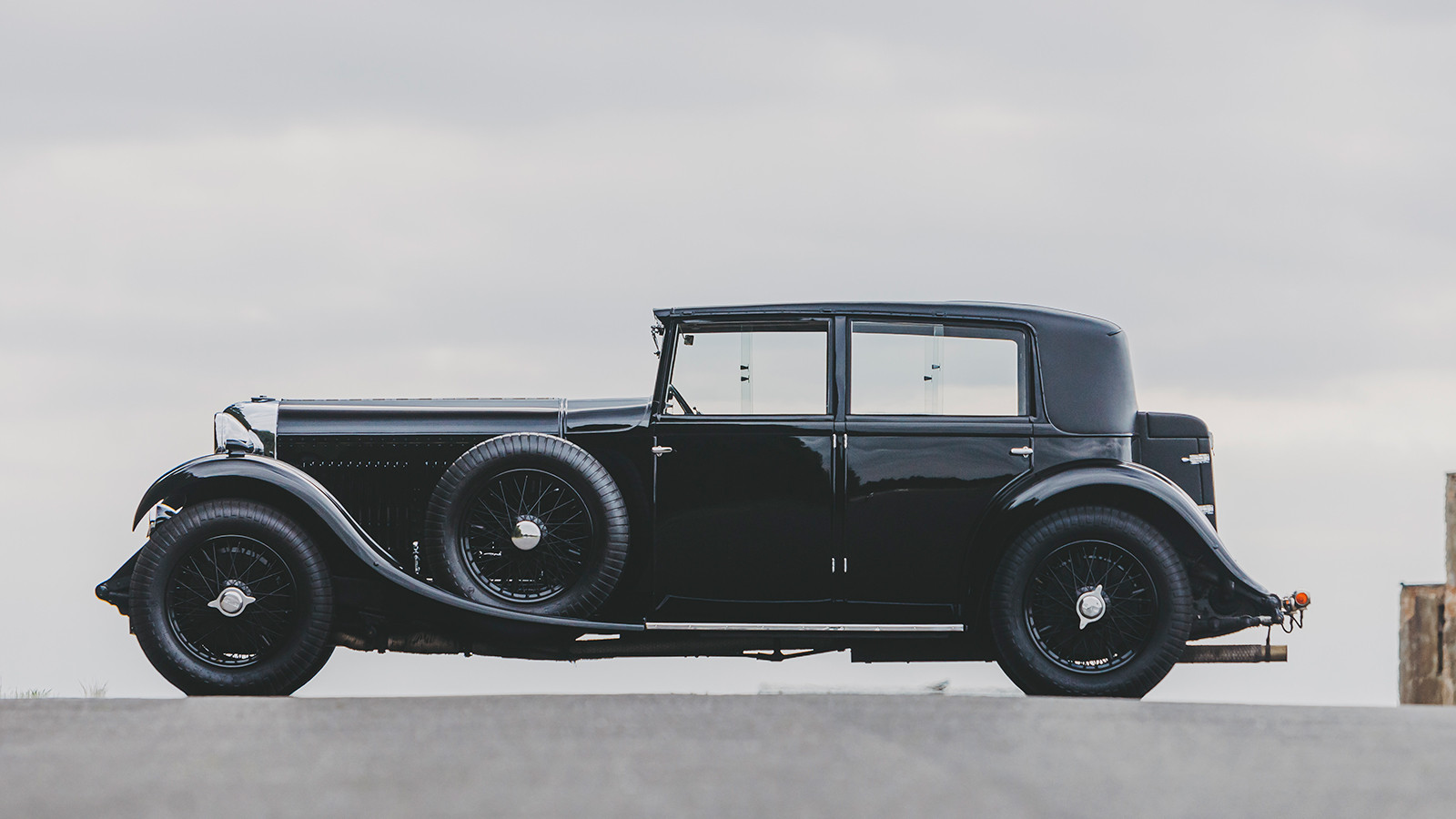

The Bentley 8 Litre and its contemporaries were generally sold as chassis, to which one of many coachbuilt bodies could be fitted, invariably having a significant bearing on the car’s maximum speed.

We’ve chosen this model because, according to leading marque authority Dr Clare Hay in Bentley – The Vintage Years, any 8 Litre could achieve a genuine 104mph, even when specified with the bluffest, heaviest saloon body.

Moreover, WO Bentley achieved not only the first 100mph lap of Brooklands by a closed car in a two-door 8 Litre, but also 107.3mph at Montlhéry with Herbert Kensington-Moir.

-

1930s: Bentley 8 Litre (cont.)

While it’s true that the odd rival with light and rakish metalwork was tested at fractionally higher speeds during this decade, it’s also true that 8 Litre rolling chassis – its 200bhp output trouncing most – would have left the works of coachbuilders such as Mulliner and Vanden Plas with performance-enhancing bodywork, too.

Bentley’s claim for it being the world’s fastest production chassis at the 8 Litre’s Earls Court debut in 1930 is the final rationale, which quashes all variables.

And it’s the ‘baseline’ saloon that we have with us today, the second of 100 8 Litres built, The Autocar test car and originally the property of WO himself, now faithfully restored and Bentley-owned.

You have to wonder if, when he pushed the starter button for the first time, WO realised how close to the financial precipice his firm actually was.

-

1930s: Bentley 8 Litre (cont.)

“I have always wanted to produce a dead silent 100mph car and now I think that we have done it,” he remarked.

But it came at a huge cost that, allied to the economic turmoil following Wall Street’s 1929 collapse, sent Bentley Motors into receivership just nine months after production commenced.

But what a way to go.

The 8 Litre’s engine alone was a masterpiece, incorporating all of Bentley’s state-of-the-art technology.

With its monobloc overhead-cam straight-six, four valves per cylinder (as was the Bentley norm), twin-spark ignition and a crankcase forged from Elektron (an expensive magnesium alloy), you can start to see why the rolling chassis alone cost £1850, an exorbitant price at the time.

-

1930s: Bentley 8 Litre (cont.)

The 8 Litre’s substantial ladder-frame chassis came in either 156in or 144in lengths, suspended by semi-elliptic leaf springs and controlled by friction dampers at the front and hydraulic lever-arms at the rear.

Braking was by mighty 15.7in drums all round, with vacuum-servo assistance.

What a swathe this behemoth must have cut back in the day.

WO used the car as it was intended on many occasions, with one long schlep from Dieppe to Cannes completed, he claimed: “In the day, without having to switch on the lights, cruising at 85mph for hour after hour.”

‘Sammy’ Davis, The Autocar’s legendary scribe, was equally enthusiastic, so much so that he headlined his 1930 road test of the 8 Litre: ‘Motoring in its Very Highest Form’.

-

1930s: Bentley 8 Litre (cont.)

Perched in this 8 Litre’s gentlemen’s club of a cabin, you can see why – and appreciate just what a leap forward it was from the 30-98.

Given its vast size, it’s narrow up front with a passenger alongside (albeit more capacious in the rear), not helped by the gearlever close to your right knee and the large, four-spoke steering wheel with its hub – sprouting three small levers for mixture/throttle/ignition – not far from your chest.

Engage the thermostatic fan (a recent addition) and, after a press of the starter, you’re just aware of six 1.3-litre cylinders whispering into life.

Snick the conventional H-pattern shift into first, noting its light, smooth action, and pull away, thankful of a return to a throttle on the right.

-

1930s: Bentley 8 Litre (cont.)

If I’ve ever sat behind a longer and more imposing bonnet, I can’t recall it; you really do feel like the captain of a very exclusive cruise ship.

Torque is copious, and you can see why Bentley was so bullish about the 8 Litre’s ability to accelerate from walking pace to more than 100mph in top gear without fuss.

Gearchanges through the four-speed crash ’box need to be timed carefully – not too slow, not too fast – but once in top, you settle back and enjoy the ride.

Naturally, with such a long wheelbase, everything happens gradually when you change direction, but the 8 Litre rolls surprisingly little – the upside to its fairly firm ride.

-

1930s: Bentley 8 Litre (cont.)

You also quickly learn to deliver steering from lower down on the wheel’s thick rim to avoid pinching your fingers between it and the dash top’s veneered surface, mid-bend.

Really this is a car in which to waft, par excellence.

As a saloon, its large, tall body finds any excuse to creak, flex and shimmy across even smooth surfaces, so for me it would have to be one of the 10 cars that were specified from new with open touring bodies.

And then I’d be heading for Cannes like a shot.

Thanks to: Bentley Motors (bentleymotors.com)

-

1930s: Bentley 8 Litre (cont.)

Factfile

Sold/number built 1930-’31/100

Engine iron monobloc with Elektron crankcase, ohc 7983cc straight-six, twin carburettors

Max power 200bhp @ 3500rpm

Max torque n/a

Transmission four-speed manual, RWD

Suspension: front friction dampers rear live axle, lever-arm dampers; semi-elliptic leaf springs f/r

Steering worm and sector

Brakes drums, with servo

Weight 5377lb (2439kg)

0-60mph n/a

Top speed 104-110mph (depending on body type)

Price new £1850 (rolling chassis only) -

1940s: Jaguar XK120

Top speed: 132.6mph

Of all the cars gathered here today, and taking into account the vagaries of inflation, the Jaguar XK120 was not only the least expensive when it was new, but also a relative bargain.

Who would have thought that £1263 would buy what was, in 1948, not just the UK’s but the world’s fastest production car?

Ironically, Jaguar boss Bill (Sir William from 1956) Lyons didn’t initially put his weight behind the model.

His focus was the MkVII, set to be Jaguar’s first 100mph saloon and powered by an all-new, highly sophisticated straight-six engine developed during the war years by the in-house team of William Heynes, Claude Baily and Walter Hassan.

But with completion of the first car delayed for its 1948 Earls Court debut, Lyons chose instead to showcase the XK120.

-

1940s: Jaguar XK120 (cont.)

Audiences were stunned.

What had been seen by Jaguar as a novel – but not particularly commercial – offering changed people’s views of what a modern sports car should look like.

Using the MkVII’s chassis and engine, albeit in highly modified forms, everything about the XK120 show car shouted speed, from its low-slung body’s exquisite, flowing lines to its spatted rear wheels and raked radiator grille.

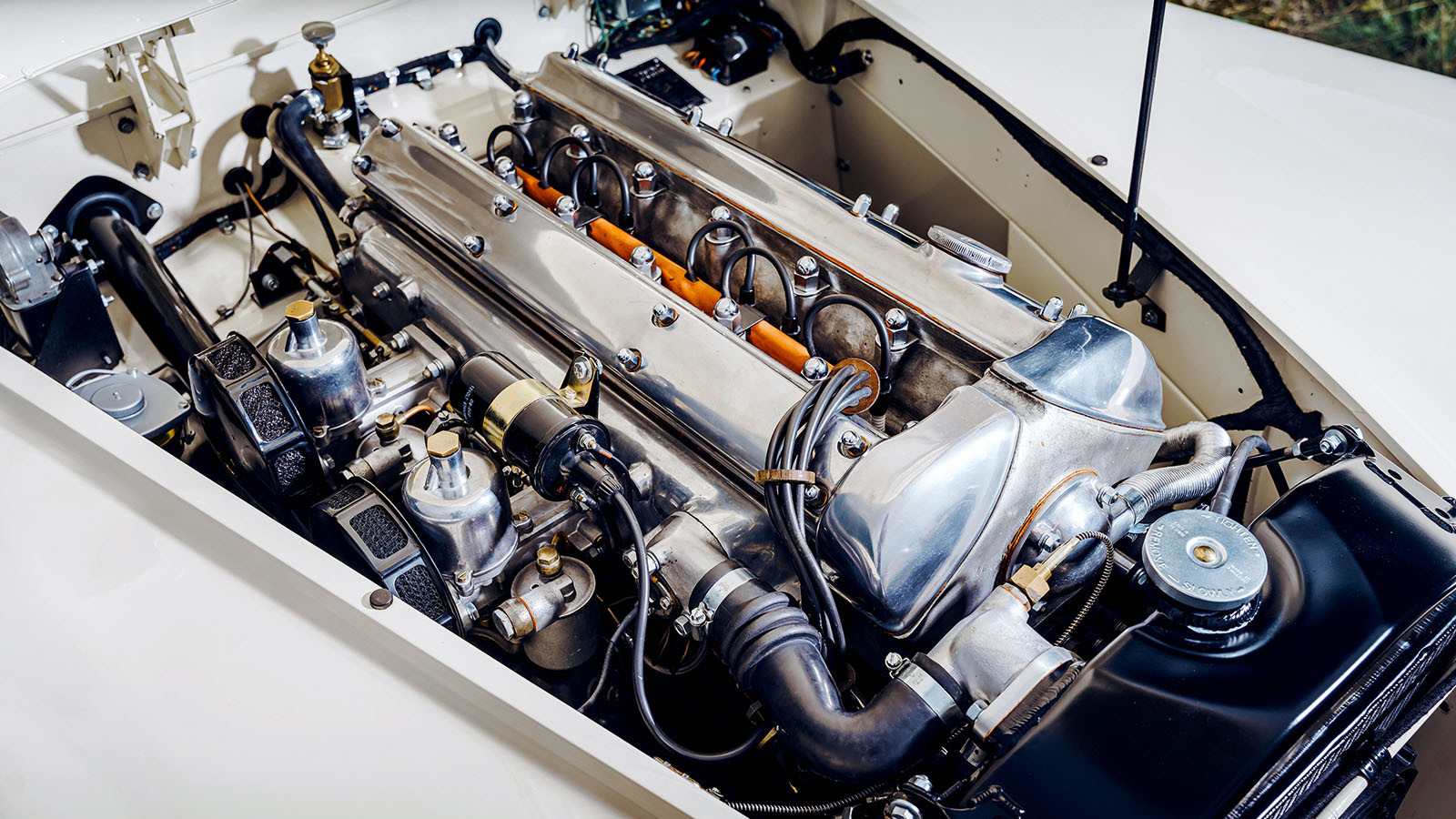

The XK120’s advanced, double-overhead-cam ‘six’ with hemispherical combustion chambers and inclined valves was tuned to develop 160bhp, with 195lb ft of torque at just 2500rpm.

A steel chassis with independent front suspension and an all-aluminium body (changed to steel in 1950, adding 112lb) meant the new Jaguar genuinely was a look into the automotive future.

-

1940s: Jaguar XK120 (cont.)

As was its top speed.

While the ‘120’ moniker was derived from near enough the car’s official Vmax, factory test driver Ron ‘Soapy’ Sutton achieved 126.4mph on Belgium’s Ostend-Jabbeke motorway, validated by the local Royal Automobile Club.

The car ran a catalogued taller top-gear ratio, but was otherwise standard.

He then replaced the full-sized split windscreen with a single aeroscreen and recorded a two-way average of 132.6mph, hence our headline figure here.

Even in The Motor’s impartial hands, the first prototype XK120 accelerated from 0-60mph in 10 secs and hit 124.6mph with its hood and sidescreens in place.

-

1940s: Jaguar XK120 (cont.)

Competition was the natural showground for the XK120, and it wasn’t long before Le Mans, the Targa Florio and the Mille Miglia were ticked off Jaguar’s to-do list, each with varying degrees of success.

Rallying proved to be its forte, however, and the now famous NUB 120, campaigned by Ian Appleyard and his wife Pat (Lyons’ daughter), took two RAC Rally wins, victory in the 1951 Tulip Rally and a Gold Cup for finishing three Alpine Trials with no penalty points.

Today, it feels appropriate that our test car is a tribute to ‘NUB’.

Built in 1950, this Jaguar-owned XK120 has been prepared for the modern-day Mille Miglia, complete with Brantz digital rally timers on the passenger side of the dashboard and a pair of analogue Bremonts set high below the dash-top-mounted rear-view mirror.

-

1940s: Jaguar XK120 (cont.)

Otherwise, apart from a fire extinguisher in the passenger footwell, the car’s interior is near-standard.

Once you’ve managed to prise yourself into the snug-fitting, leather-trimmed bucket seat (the small door and large steering wheel favour the lithe), you face a simple dashboard inset with two widely spaced main clocks for revs and speed, along with three small, secondary dials covering oil pressure/water temperature, amps and fuel.

A chromed fly-off handbrake is on the passenger side of the transmission tunnel, from where a short gearlever sprouts.

The four-spoke steering wheel – white on this car – is large and near-vertical, with a protruding conical boss that sits nicely in line with your sternum…

-

1940s: Jaguar XK120 (cont.)

Wait for the float chambers of the twin SUs to fill before thumbing the starter, and the 3442cc ‘six’ fires into life, emitting a sharp bark through its twin exhausts.

There’s no detent for reverse in the Moss ’box, so you take care not to shift the lever too far to the left and forward to select first.

Driving is simplicity itself; it makes few demands on you, thanks to main controls that are light and progressive in their action.

The gearbox lives up to its reputation by being precise but easy to catch out, with a short grate of gears if you dare to rush it.

-

1940s: Jaguar XK120 (cont.)

Which you’re prone to do, because this car just cries out to be driven hard.

Feel through the Burman steering box is excellent, and as you gather confidence and turn in to bends with more conviction, your position – low to the car’s centre of gravity and immediately before the rear axle – gives you an intimacy with its dynamics that must have been a real boon on those ice-covered Alpine roads.

Gearing is short on this car, so there will be no chasing of three-figure-plus speeds today, but it doesn’t require much imagination to put yourself on that empty Belgian motorway 70 years ago, crouched behind a tiny aeroscreen and watching the numbers climb.

Thanks to: Jaguar Land Rover Classic (jaguarlandroverclassic.com)

-

1940s: Jaguar XK120 (cont.)

Factfile

Sold/number built 1948-’54/7612

Engine iron-block, alloy-head, dohc 3442cc straight-six, twin SU carburettors

Max power 160bhp @ 5200rpm

Max torque 195lb ft @ 2500rpm

Transmission four-speed manual, RWD

Suspension: front independent, by double wishbones, torsion bars, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar rear live axle, semi-elliptic leaf springs, lever-arm dampers

Steering Burman recirculating ball

Brakes 12in (305mm) drums

Weight 2919lb (1324kg)

0-60mph 12 secs

Top speed 132.6mph (when fitted with an aeroscreen)

Price new £1263 3s 11d (1948) -

1950s: Mercedes-Benz 300SL

Top speed: 163mph

They say that racing improves the breed, but in the case of the Mercedes-Benz 300SL ‘Gullwing’ Coupé, it actually inspired its creation.

At the start of the 1950s, competition was seen as the perfect way for Mercedes to re-establish itself as a pinnacle car maker.

By 1951, the concept of a lightweight, ultra-streamlined racer had been drawn up by legendary engineer Rudolf Uhlenhaut, borrowing the 2996cc, overhead-cam straight-six from the mighty 300 ‘Adenauer’ saloon.

In 1952 the W194 became a reality, and Mercedes campaigned it at the Mille Miglia, Le Mans and the Carrera Panamericana, taking victory at each event and proving that, despite its meagre power, a low-weight, aerodynamic recipe could literally win the day.

-

1950s: Mercedes-Benz 300SL (cont.)

Had it not been for the vision of one Max Hoffman, Mercedes’ US importer, however, the W194 might well have rested on its growing number of laurels.

Hoffman saw the appeal of productionising the W194 for his affluent, enthusiast clientele and proposed the idea to the Benz board, reinforced with a pre-order for 1000 cars.

In what must have been a quite humbling challenge to Teutonic pride, Mercedes came on board and agreed to start production of what was to become the 300SL Coupé.

Can you think of another production car that blitzed its competition sibling’s power output?

-

1950s: Mercedes-Benz 300SL (cont.)

Me neither. But by swapping the W194’s triple Solexes for a groundbreaking mechanical fuel-injection system from Bosch, the 300SL was instantly given 40% more power – to the tune of 240bhp – allowing Mercedes to claim a barely conceivable 163mph maximum (depending on axle ratio) when the model was launched at New York’s International Motor Sports Show in 1954.

The 300SL’s design and engineering were extreme in every way.

Based around the W194’s principle of a tubular steel spaceframe chassis, Uhlenhaut’s team clothed the car with a low and slippery steel body – apart from the bonnet, bootlid, sills and door skins, which were aluminium.

The width of the W194-derived frame dictated a radically inset cabin, which begat not only obvious aero benefits but also the challenge of ingress and exit.

-

1950s: Mercedes-Benz 300SL (cont.)

Gullwing-style doors were the only option, developed from the W194’s smaller and less user-friendly items.

Uhlenhaut’s other challenge was packaging the 300’s tall, in-line six-cylinder engine while maintaining a low bonnet profile to aid aerodynamics.

Consequently, thanks in part to the addition of a generous 15-litre dry sump, the engine was canted over at a 50º angle, which also meant fitting a colossal intake manifold, almost as wide as the entire installation.

With the majority of sales aimed at demanding US buyers, there was a concern that such unprecedented engineering could come back to bite Mercedes if not thoroughly proven.

-

1950s: Mercedes-Benz 300SL (cont.)

As a result, every one of the 300SL Coupé’s engines was bench-tested at the works for 24 hours, including four hours at full load.

It was then stripped down, measured, inspected and reassembled, before being fitted to the car.

If ergonomics signify a commensurate progress in outright performance, then the Mercedes should be hitting the double-ton: you have to keep reminding yourself that this is a 70-year-old car, given how well thought-out and modern-looking is its cabin and how instantly at home you feel in it.

Sure, with the gullwing door raised you have to climb over a high and wide sill, as you would on entering a closed Le Mans racer, but the steering wheel tilts to make the process not quite so taxing.

-

1950s: Mercedes-Benz 300SL (cont.)

Comfortably ensconced and facing the big, white two-spoke wheel, you note how close you are to the 300’s centre line.

Two large dials for revs and speed (tantalisingly and almost precisely suggesting 163mph) sit in the main binnacle, with four further clocks dotted around the body-coloured dash.

Three slider controls for ventilation look impressively avant-garde for a ’50s car, as does the way the main controls are sited so perfectly for the driver, making this the least intimidating machine of all those gathered today.

Hardly any acclimatisation is needed from the off. The high-mounted, H-pattern gearshift is a doddle, while the clutch is nicely weighted and precise in its action.

-

1950s: Mercedes-Benz 300SL (cont.)

You do notice plenty of wind noise even from low speeds – you can only imagine the challenge of sealing those doors – but that’s soon forgotten as the SL’s ‘six’ emits its guttural roar from 2500rpm, after which you’re mentally playing Kraftwerk’s Autobahn as an accompaniment and being lost in the moment.

Until, that is, you reach the first bend at speed, and remember the 300SL’s narrow rear track and swing-axle rear suspension.

The steering is alive with feedback, but that also includes a mild sense of waywardness as you aim for each bend’s exit, and a reminder that this is quite a rare and valuable machine.

But it’s also an absolute jewel and, if I were pushed to choose, my favourite here today.

Thanks to Hilton & Moss (hiltonandmoss.com)

-

1950s: Mercedes-Benz 300SL (cont.)

Factfile

Sold/number built 1954-’57/1400

Engine iron-block, alloy-head, ohc 2996cc straight-six, Bosch mechanical fuel injection

Max power 240bhp @ 6100rpm

Max torque 217lb ft @ 4800rpm

Transmission four-speed manual, RWD

Suspension independent, at front by unequal-length wishbones, anti-roll bar rear diff-located swing axles, radius arms; coil springs, telescopic dampers f/r

Steering recirculating ball

Brakes drums

Weight 2855lb (1295kg)

0-60mph 9.3 secs

Top speed 163mph

Price new £4393 -

1960s: Lamborghini Miura P400

Top speed: 174mph

Nowadays, we tend to bandy around the word ‘supercar’ because, frankly, the world is awash with them.

But in 1966, the Lamborghini Miura P400 was perhaps the car for which the term was first coined.

And with a then scarcely imaginable 174mph top speed, you can see why.

The fledgling Lamborghini car company (as distinct from the well-established tractor-making concern) had rapidly come to the fore with its first production model, the 350GT.

Ferruccio Lamborghini was wedded to the idea of powerful front-engined GTs, much like rival Enzo Ferrari, but his young engineering team, led by Gian Paolo Dallara, had other ideas.

-

1960s: Lamborghini Miura P400 (cont.)

Inspired by the competition success of Ford’s GT40 and Porsche’s 904, Lamborghini was persuaded to steal a march on Ferrari with a mid-engined production car, and by 1965 the rolling chassis was revealed at the Turin Salon.

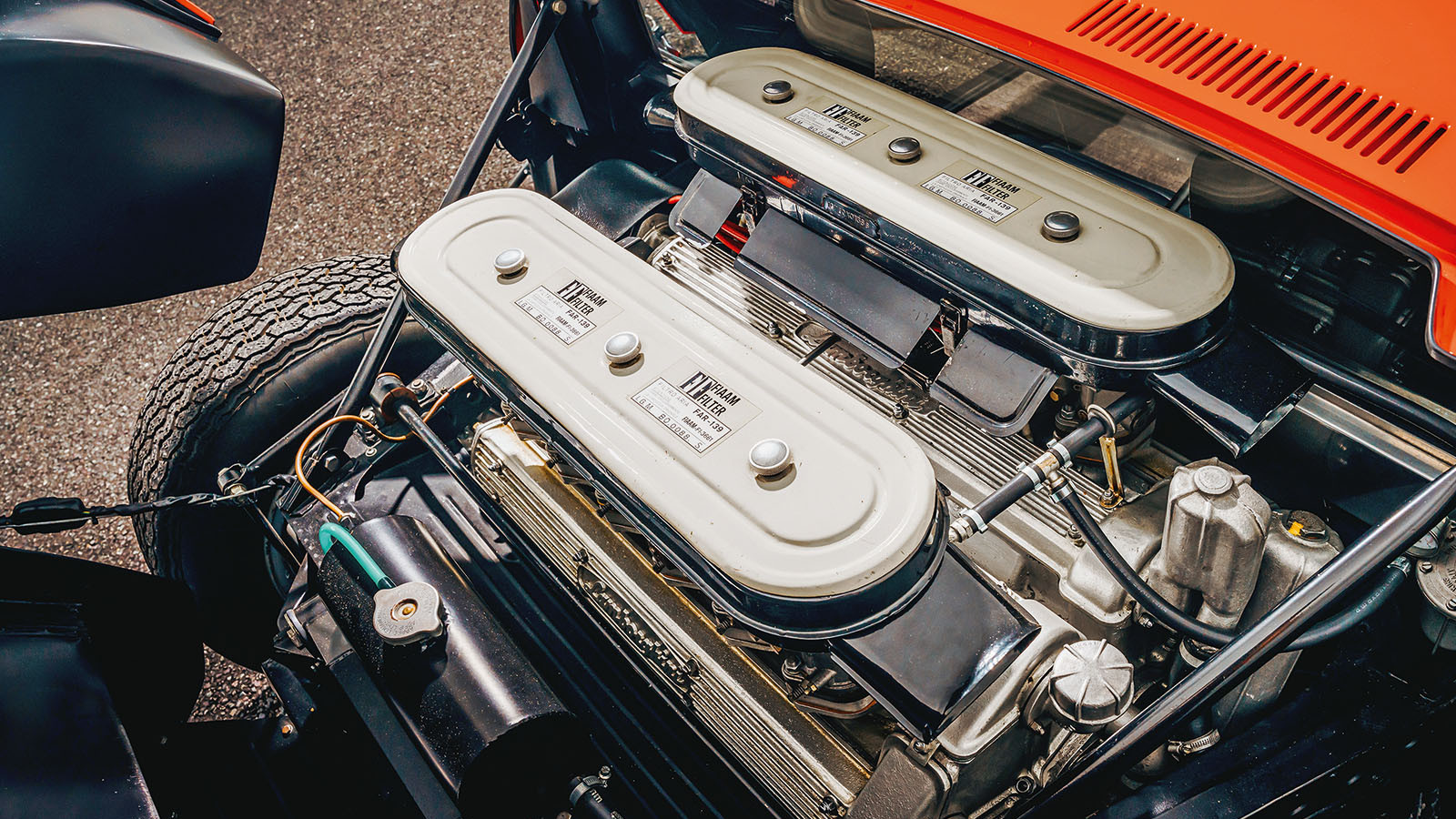

Where Lamborghini eschewed convention was the transverse location of its Giotto Bizzarrini-designed, 3929cc 60º V12, plucked from the 400GT (the 350GT’s more powerful successor).

At a stroke, not only was the engine’s weight brought closer to the car’s mid-point to sharpen handling, but space was also liberated at the rear of the chassis for some token storage.

All that was needed then was a body design that would make Enzo weep with envy.

And boy, did it succeed. Bertone was tasked with clothing the Miura’s welded-steel backbone chassis, and he gave his 25-year-old designer Marcello Gandini responsibility for overseeing the project.

-

1960s: Lamborghini Miura P400 (cont.)

To say that it was radical is an understatement when you consider that in the mid-’60s the only cars that came close to capturing such an essence of speed in their design wore roundels on their doors and were generally driven in circles.

At 41.3in (1050mm) from ground to roof, everything about the Miura’s design was focused on allowing it to spear through the air faster than anything else on the road.

From its eyelashed, pop-up headlights and sharply raked front windscreen to its distinctive slatted engine cover (which ventilated the mighty V12 while allowing some semblance of rearward vision), the Miura must have looked like something from outer space when it received its debut at the 1966 Geneva Salon.

Maybe as a statement of intent to link the Miura with the motorsport world (although it never became a competition car), one of its first post-show appearances was at the ’66 Monaco Grand Prix, where now-legendary Lamborghini test driver Bob Wallace drove VIP guests and media around the circuit.

-

1960s: Lamborghini Miura P400 (cont.)

It was probably just as well that Monaco was a relatively slow circuit, since the car’s high-speed raison d’être was called into question after production of the first P400 model commenced in 1967.

It wasn’t that Lamborghini’s 174mph claim was in doubt – Motor clipped 171mph when it tested an early press car – it was more about the car’s propensity to take flight as it approached those speeds.

The issue wasn’t fully resolved until the launch of the SV model in 1971, with slightly raised rear and lowered front suspensions to aid high-speed stability.

The above spools through your mind as you sit in this ’67 Miura P400, its immaculate Rosso Miura (nearer orange) paintwork glinting in the sun.

At 5ft 7in I fit into most cars with room to spare, but once curled into the Miura’s black-leather-trimmed seat, I have just two inches of headroom.

-

1960s: Lamborghini Miura P400 (cont.)

Everything about this car is low: two large, skeletal dials – one for revs, the other for speed up to 320kph (199mph) – dominate your sight line, while six secondary dials are angled towards you from a chunky, rectangular binnacle ahead of an open-gated five-speed gearshift.

Turn the ignition and wait for the fuel pump to deliver sufficient super unleaded, then the engine fires and fills the small cabin with a multi-cylinder soundtrack straight out of Grand Prix.

Behind, a shallow screen is all that’s between your right ear and two of the four, three-barrel Webers atop the motor, rocking as you blip the throttle.

This car is all about the engine; everything else is mere distraction.

It’s very physical to drive, partly because you need to reach so far to the canted three-spoke steering wheel, while your legs are noticeably kinked to connect with the long-travel, floor-mounted pedals.

-

1960s: Lamborghini Miura P400 (cont.)

How did actor Rossano Brazzi make it look so cool in The Italian Job?

But as you accelerate hard along Prestwold’s main straight, ergonomic failings fade away.

Gear noise competes with the V12’s roar as you touch the ton, before heel-and-toeing down through the precise, mechanical ’box for the right-hander at the end.

No issues at these speeds: the Miura feels rock-solid and stable, staying surprisingly flat through the faster bends.

If we were handing out awards for the intensity of the experience today, the Miura would win hands down.

Never before has the prefix ‘super’ seemed so appropriate.

Thanks to: Simon Drabble Cars (simondrabblecars.co.uk)

-

1960s: Lamborghini Miura P400 (cont.)

Factfile

Sold/number built 1966-’69/275

Engine all-alloy, dohc-per-bank 3929cc V12, with four triple-choke Weber carburettors

Max power 350bhp @ 7000rpm

Max torque 300lb ft @ 5500rpm

Transmission five-speed manual transaxle, RWD

Suspension independent, by double wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers and anti-roll bar f/r

Steering rack and pinion

Brakes discs

Weight 2849lb (1292kg)

0-60mph 6.7 secs

Top speed 174mph

Price new £9529 -

1970s: Ferrari 365GT4 BB

Top speed: 188mph

Our first Ferrari entry here was not only the fastest car of the 1970s (based on the factory’s own claim of 188mph), but a significant one because it marked the start of a mid-engined era for Maranello’s 12-cylinder, two-seater cars that was to endure for nearly a quarter of a century.

The stars had clearly aligned when Ferrari introduced the prototype 365GT4 BB at the 1971 Turin Salon.

There was already precedent for its decision to go mid-engined, with the 1967 Dino 206 (and later 246) so configured.

And it would have been impossible for Ferrari to ignore that its four-year-old, front-engined 365GTB/4 Daytona had always been head-to-head with Lamborghini’s mid-engined Miura, then the epitome of advanced automotive engineering.

-

1970s: Ferrari 365GT4 BB (cont.)

It wasn’t as if a Ferrari with a 12-cylinder motor mounted amidships was a new concept.

The benefits in terms of sharper handling and superior aerodynamics of an engine located aft of the cockpit had been proved since 1964 in Maranello’s 512 racer.

It also pioneered a new engine design: Ferrari was the first car maker to employ a ‘flat’, or horizontally opposed, 12-cylinder unit, the packaging of which would have been impractical in a front-engined racer.

When the production-ready 365 Berlinetta Boxer arrived in 1973, this technology was fully embraced.

In effect a wide-angled vee, with 180º separating each bank of cylinders, its all-new 4.4-litre flat-12 produced a solid 380bhp at 7200rpm and 301lb ft of torque at 3900rpm.

-

1970s: Ferrari 365GT4 BB (cont.)

It was a wide unit, but the configuration kept mass lower down in the chassis, although with its transaxle mounted below, beside the wet sump (a dry sump didn’t appear until the later 512BB), that advantage was never fully exploited.

In the BB’s earliest form there is a simplicity and purity to the Pininfarina-penned shape that later derivatives were never quite able to match.

Based on the coachbuilder’s 1968 P6 concept car, it was shorn of all unnecessary addenda.

A low, slender nose, with pop-up headlights and possibly the largest indicator lenses ever seen, housed a shallow radiator and small ‘frunk’, suitable only for overnight luggage.

-

1970s: Ferrari 365GT4 BB (cont.)

Avoiding the need for unsightly side-scoops, an aileron was neatly integrated into the rear roofline, overlapping the Boxer’s vertical back window and delivering air to four triple-choke Weber carburettors.

Ironically, the 365’s trademark six tail-lights and sextet of peashooter exhausts were never part of the prototype’s design, which had four of each, just like the later 512.

‘Our’ 365 BB is rather special, having been Ferrari’s 1975 British motor show car.

It’s wide even by modern standards, with hardly a flat surface adorning any panels, themselves sumptuously curved and neatly proportioned compared with those of Lamborghini’s Brutalist period rival, the wild Countach.

-

1970s: Ferrari 365GT4 BB (cont.)

Those scoopless flanks are unspoilt by mirrors or doorhandles, the latter being replaced by short ‘fingers’ that pull back from the base of the windowframes to gain entry.

And any Ferrari that rides on classic Campagnolo alloys – especially if they’re shod with period-style 215/70 Michelin XWXs – is proper in my book.

Entry over a wide sill puts you satisfyingly close to the car’s centre line and perched on a leather chair that demands only a slightly long-armed, short-legged position behind the non-standard three-spoke steering wheel.

As is the norm for Ferrari two-seaters from this era, only dials populate the upper dashboard – eight of them in this case – with the heater controls (including optional and working air-con) and electric-window switches all consigned to the narrow, leather-trimmed central gear tunnel.

-

1970s: Ferrari 365GT4 BB (cont.)

Fire up the engine from cold with a conventional turn of the key, and the initial rip-snort from the Webers is quickly replaced by a smooth and cultivated 12-pot timbre.

Select the dogleg first in the traditional open-gated ’box and, other than getting used to a quite sticky throttle action, all the main controls are light and linear.

The cabin is bright and airy, with great vision all round, including over the low scuttle and through the pillar-box slot of a rear window. Who needs door mirrors?

Wait for the oil to warm through and then push hard on the long-travel throttle.

-

1970s: Ferrari 365GT4 BB (cont.)

The Webers clear their throats and the engine note hardens into a trumpeting roar as the tacho’s needle reaches for its 7600rpm redline and a good deal of those 380 horses are unleashed.

As we lap Prestwold, clipping just shy of 100mph down the straights, I’m barely flexing my right foot once up to speed: there’s so much more to explore, if only we had the space.

The steering is deliciously light, telegraphing every nuance of the track’s surface through the wheel’s rim.

You can’t avoid comparing it with the Miura and concluding that, if you had to traverse whole countries in the 1970s, this would have been your weapon of choice, with its easy-going savoir faire and abundant reserves of power to banish any contender from its rear-view mirror.

Thanks to: Simon Drabble Cars (simondrabblecars.co.uk) and Guy Newton

-

1970s: Ferrari 365GT4 BB (cont.)

Factfile

Sold/number built 1973-’76/387

Engine all-alloy, dohc-per-bank 4391cc flat-12, four triple-choke Weber 40IF3C carburettors

Max power 380bhp @ 7200rpm

Max torque 301lb ft @ 3900rpm

Transmission five-speed manual transaxle, RWD

Suspension independent, by double wishbones, coil springs (twin at rear), telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar f/r

Steering rack and pinion

Brakes ventilated discs, with servo

Weight 3420lb (1551kg)

0-60mph 6.5 secs

Top speed 188mph

Price new £14,255 -

1980s: Ferrari F40

Top speed: 201mph

And so we arrive at a notable benchmark on this journey: the Ferrari F40 was the first production car to exceed the magic ‘double-ton’.

You could argue that the F40 owes its existence to healthy opportunism rather than a well-planned marketing strategy.

Ferrari’s sales had faltered in the early 1980s, with fears that its products were turning ‘soft’ under Fiat’s corporate blanket.

A quick solution was needed to turn the tide and, in 1984, Maranello engineer Nicola Materazzi believed that he had one.

His plan was to use Group B rallying as a testbed for a more hardcore road product.

Approval was given, which resulted in a skunkworks development of what became the 288GTO, with the 288 Evoluzione its competition flag-bearer.

-

1980s: Ferrari F40 (cont.)

Alas, by the time the programme was complete Group B had been dissolved and, while the 288GTO successfully expunged any lingering doubts about Ferrari’s softness, there was clearly scope to do more.

Much more, in fact. The F40 replaced the 288GTO in 1987 and, despite the new machine adopting a slightly larger (2936cc versus 2855cc) version of the GTO’s twin-turbocharged V8, it was set to be an altogether more high-tech, uncompromising and brutally fast proposition.

Weight reduction and aerodynamics were the F40 development team’s watchwords from the start.

A clean-sheet design by Leonardo Fioravanti at Pininfarina housed the F40’s mighty powerplant in a tubular spaceframe chassis, clothed with bonded Kevlar panels and carbonfibre door skins, bonnet and boot panels.

All but the essentials were stripped from the cabin, leaving ultra-lightweight bucket seats, a pared-down, felt-covered dash and pull-cords for doorhandles, all contributing to a sylphlike 2723lb kerbweight.

-

1980s: Ferrari F40 (cont.)

Wind-tunnel testing resulted in a relatively low (for a sports car) Cd figure of 0.34, and 15,000 miles of testing at Nardò, including 48 hours at a 187mph average, ironed out any high-speed stability issues.

Engine power was substantially increased versus the 288GTO, with 478bhp at a typically high 7000rpm.

But a hefty 426lb ft of torque at a relatively low 4000rpm was a portend to the prodigious mid-range urge on tap.

As with the body and interior, weight was shed from the powertrain, with its sump, cylinder-head covers, intake manifolds and gearbox bellhousing all cast from ultra-expensive magnesium.

Enzo Ferrari, fully behind the programme, demanded the car be ready within 11 months, in time for the company’s 40th anniversary, hence its eventual moniker.

It turned out to be the last car Enzo approved, and with rumours already rife about his ill health (he died the following year), it was clear demand would outstrip the proposed 400-car build.

By 1992, when production ceased, 1315 F40s had been sold.

-

1980s: Ferrari F40 (cont.)

The 1990 example with us today belongs to Wolfrace Wheels founder Barry Treacy, who has owned it almost from new.

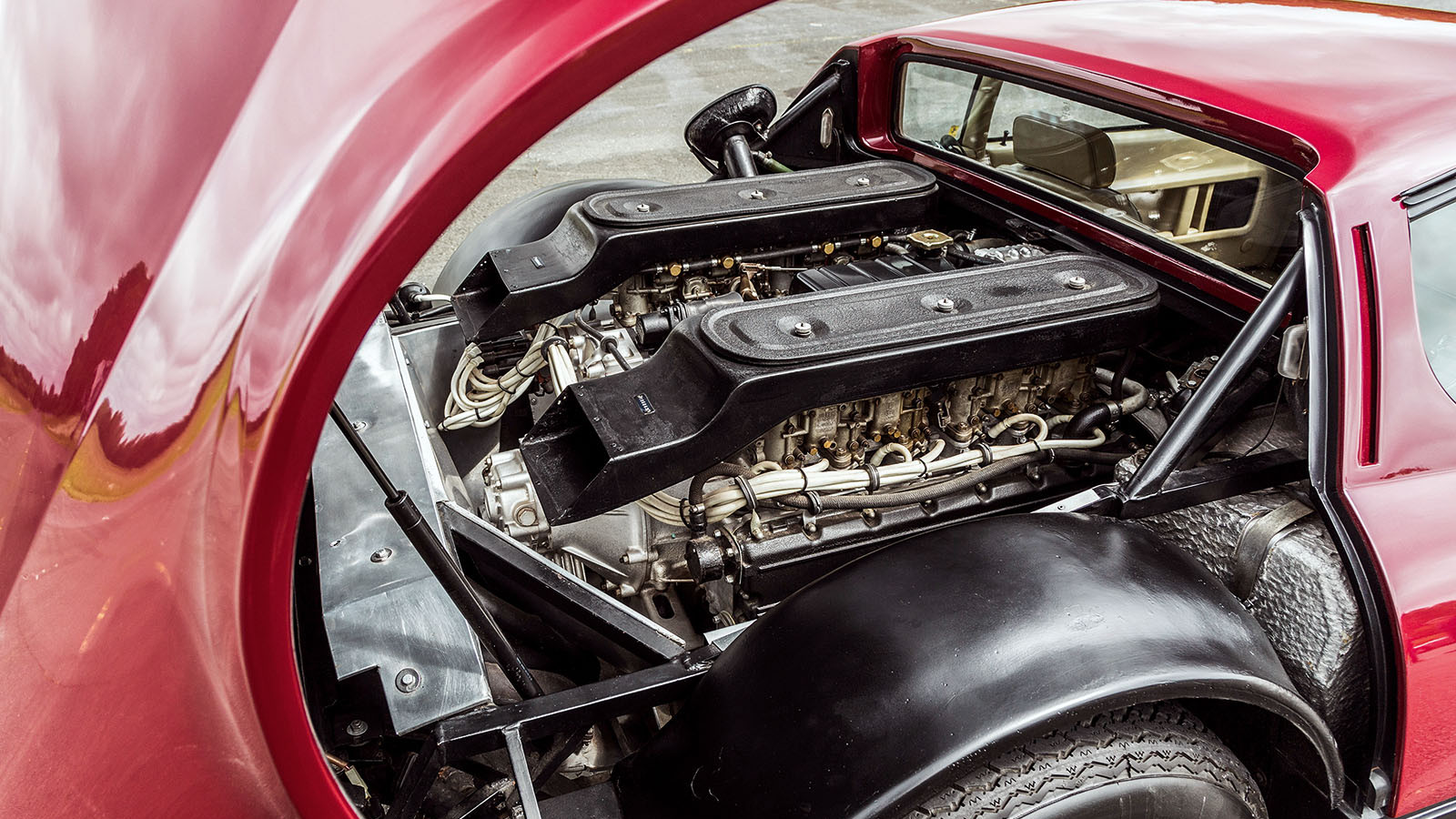

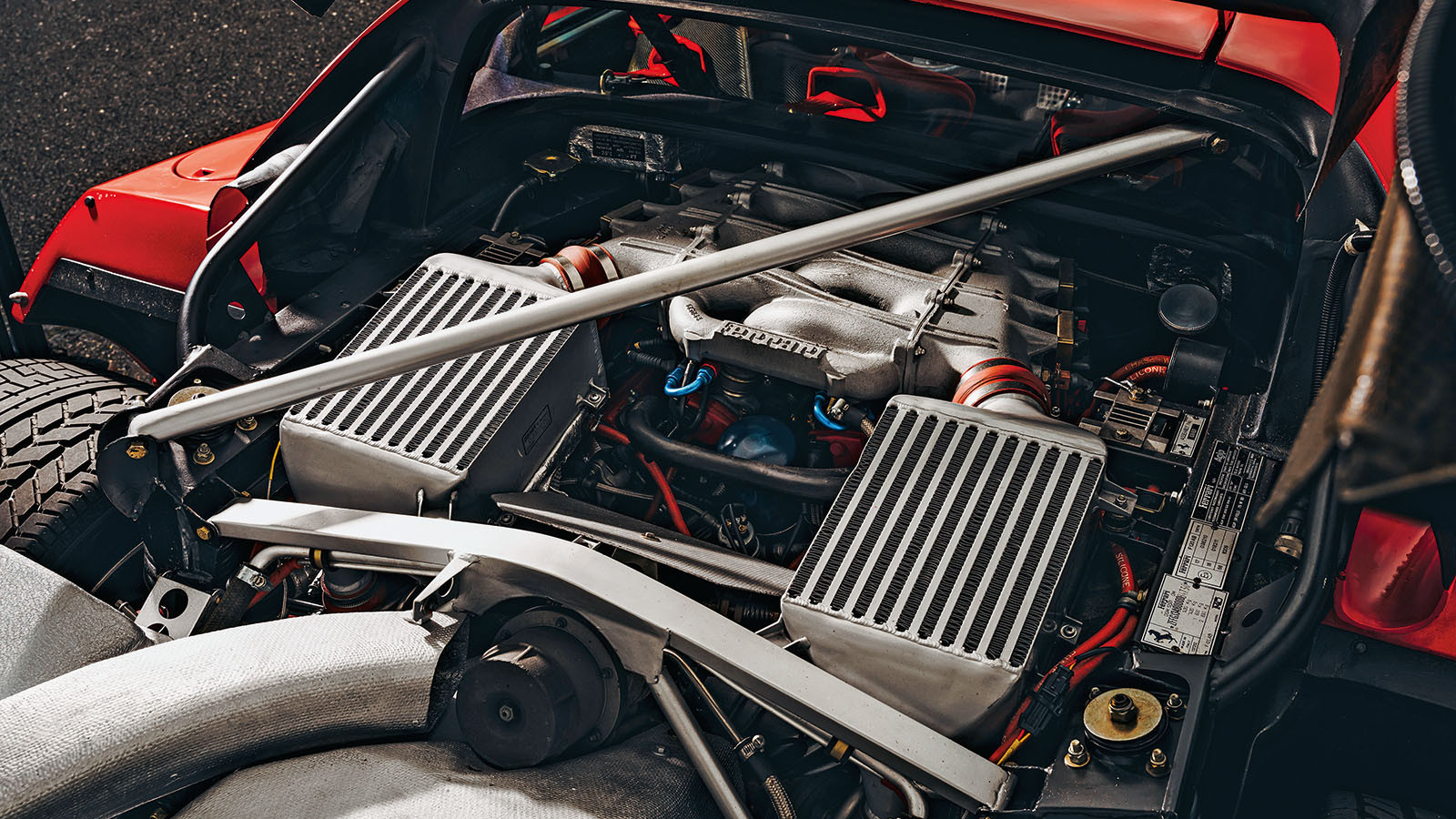

Lifting the F40’s rear clam reveals that it is simply a racing car masquerading as something with legal access to a public road.

Huge 335-section tyres on 17in rims suspended by exquisite-looking unequal-length upper and lower wishbones dominate the view.

The 90º V8 sits ahead of them, nestled close to the bulkhead with the turbochargers’ two massive intercoolers partly shrouding it.

You could gaze at it for ever. But we’re here to drive it on track.

Step over the high, carbonfibre-covered sill and drop into the Sabelt bucket seat.

-

1980s: Ferrari F40 (cont.)

The drilled aluminium pedals are slightly offset to the right (all F40s are left-hand drive), but overall the driving position is comfortable, if a little long-armed.

A simple binnacle containing speed, revs, water temperature and turbo boost is supplemented by three smaller dials in the centre of the dashboard for oil temperature and pressure, and fuel.

There really isn’t much else to distract you.

Twist the key and the V8 springs into life, more refined than you expect it to be.

It demands plenty of revs to pull away, though, not helped by the heavy and quite abrupt clutch.

Steering through the unassisted rim remains weighty even after you’ve gathered speed, but it’s a delight: high-geared, taut and alive with feel.

-

1980s: Ferrari F40 (cont.)

As you gradually build speed through the bends, it’s a real confidence-giver.

Then it’s time to unleash the F40’s near-500bhp arsenal.

Turbo lag? Nowhere near what you might expect, with the drama building progressively after 3000rpm before reaching quite absurd levels of thrust as the twin IHI turbos spool towards their maximum 1.1bar boost from about 3800rpm.

The soundtrack has the aural appeal of an older Formula One V8, but it is accompanied between gearshifts by the loudest wastegate ‘whoosh’ I’ve experienced this side of a modified Mitsubishi Evo VI.

Subjectively, apart from the McLaren, nothing else here today feels as damned fierce as the F40 in its mid-range.

Not for the faint-hearted, perhaps, but the perfect tonic for those accusations of Ferrari softness.

Thanks to: Will Brown at the Ferrari Owners’ Club of Great Britain (ferrariownersclub.co.uk)

-

1980s: Ferrari F40 (cont.)

Factfile

Sold/number built 1987-’92/1315

Engine all-alloy, dohc-per-bank 2936cc V8, with electronic fuel injection and twin IHI turbochargers

Max power 478bhp @ 7000rpm

Max torque 426lb ft @ 4000rpm

Transmission five-speed manual transaxle, RWD

Suspension independent, by unequal-length wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers and anti-roll bar f/r

Steering rack and pinion

Brakes ventilated discs

Weight 2723lb (1235kg)

0-60mph 4.1 secs

Top speed 201mph

Price new £193,000 (1987) -

1990s: McLaren F1

Top speed: 240.1mph

It wasn’t meant to be all about the top speed.

The McLaren F1 was conceived not to be the fastest sports car in the world, but simply the best sports car in the world.

That it turned out to be the fastest car of its decade – and went on to win Le Mans outright – were perhaps inevitable by-products of the purity of its original design.

By the late 1980s, McLaren had established itself as the most successful Grand Prix team of its era.

However, McLaren’s technical director, Gordon Murray, was said to be increasingly disenchanted with the Formula One circus and had for some decades been nurturing the idea of creating a pure, roadgoing sports car.

-

1990s: McLaren F1 (cont.)

“I’d had the idea for this car in the back of an exercise book since the ’60s,” Murray told Autocar & Motor.

McLaren chief Ron Dennis initially took quite a lot of convincing to take on such a project, but in 1989 Murray stepped back from designing Formula One machines and McLaren Cars Ltd was created with the intention of bringing Murray’s road car dream to life.

By May 1990 he’d assembled the right team. “I sat down everyone we’d hired, and gave them every thought I’d had on this car in one marathon briefing,” he said. “It took 10 hours.”

Major landmarks in sports car engineering quickly followed.

McLaren initially approached Honda, the race team’s engine supplier at the time, to provide the powerplant, but although the Japanese manufacturer was at the top of Murray’s wish-list, in the end McLaren went with BMW, which set about creating a bespoke, naturally aspirated 6.1-litre V12.

-

1990s: McLaren F1 (cont.)

McLaren’s in-house team was more familiar with composites, and a three-seater carbonfibre tub was key to Murray’s aim of bringing the F1 to the road at less than 1000kg.

It placed the driver centrally between two passengers, with the powertrain mounted behind.

In the end, McLaren couldn’t get carbon brakes to work properly at road speeds, so with iron discs the car arrived weighing more than originally had been hoped: Autocar & Motor weighed the F1 at 1138kg for the car’s 1994 road test, including half a tank of fuel.

But that engine made up for it.

The original target had been for around 550bhp, yet in its final form the astonishing BMW engine made 627bhp at 7400rpm, resulting in a power-to-weight ratio of 551bhp per tonne, and 479lb ft of torque from 4000-7000rpm.

-

1990s: McLaren F1 (cont.)

The car would hit 60mph from rest in 3.2 secs and 100mph in just 6.3 secs.

While its top speed was still estimated to be ‘in excess of 230mph’, a prototype with only 580bhp had already

hit 231mph around the banked test track at Nardò proving ground in Italy.In broader terms, the F1 weighed less than a contemporary Volkswagen Golf hatchback but had more power than a Honda NSX and a Ferrari 348GTB combined.

It used a six-speed manual gearbox, there was no power steering and the brakes were unassisted, too.

“The F1,” Ron Dennis said of the car in 1993, “is all about the pleasure of knowing that what’s doing it right is you.”

-

1990s: McLaren F1 (cont.)

That same pleasure is what makes an F1 so exciting today.

We didn’t drive the car in these pictures, a GTR racer converted for road use and finished in evocative Papaya Orange: McLaren built just 106 F1s and their rarity, along with the elevated status that goes with it, means values have swollen by more than 30 times from the original list price – and figures such as those aren’t received well by insurers.

But two years ago I drove one at a proving ground for long enough to melt the rear numberplate, and the experience will stay etched in my mind for as long as I retain my faculties.

The V12 starts without the histrionics that accompany so many of today’s supercars, but its smoothness is uncanny, and as revs rise it takes on as much drama as any of the world’s great engines.

-

1990s: McLaren F1 (cont.)

Its response is pure and linear, and matched by the other controls: the gearshift is positive, the steering picks up weight as cornering forces build, and it’s engaging and involving like precious little else, with the stiff composite shell meaning that it retains a sense of responsiveness and modernity.

In its immediacy and compactness the F1 feels, in a way, not unlike a Lotus Elise – only with a frankly preposterous amount of shove behind it.

This car has a higher power-to-weight ratio than a Bugatti Chiron.

McLaren’s laid-back approach to the subject of top speed is illustrated by the fact that the firm took until 1998 to head to Volkswagen’s Ehra-Lessien test track, with an F1 modified only by having a slightly raised rev limit.

-

1990s: McLaren F1 (cont.)

Until then, the record books through the 1990s had read ‘217mph’ and ‘Jaguar XJ220’.

Andy Wallace, who had finished on the podium at Le Mans in an F1, was at the car’s wheel as the McLaren hit 240.1mph.

At the time, some publications speculated that there might never be another road car that would go so fast.

As it turned out, they were wrong…

Words: Matt Prior

Thanks to: Thomas Reinhold, McLaren Special Operations (cars.mclaren.com)

-

1990s: McLaren F1 (cont.)

Factfile

Sold/number built 1992-’97/64 (road cars only; 106 in total)

Engine all-alloy, dohc-per-bank 6064cc 60º V12, with electronic fuel injection

Max power 627bhp @ 7000rpm

Max torque 479lb ft @ 4-7000rpm

Transmission six-speed manual transaxle, RWD

Suspension independent, by double wishbones, telescopic dampers, coil springs; front anti-roll bar

Steering rack and pinion

Brakes ventilated discs

Weight 2509lb (1138kg)

0-60mph 3.2 secs

Top speed 240.1mph

Price new £634,500 -

2000s: Bugatti Veyron 16.4

Top speed: 253mph

No production car had ever been conceived from such an unreasonable brief as the 2005 Bugatti Veyron 16.4.

It was as if Ferdinand Piëch, the Volkswagen Group’s big chief and the person responsible for the Bugatti brand’s 1998 rebirth, had plucked the target numbers out of thin air, like a child might if they were asked to create a fantasy mega-car: 1000 horsepower, a top speed in excess of 250mph, and a price-tag of €1million.

Pretty please.

The plan faltered almost immediately.

After revealing the concept at the 1999 Tokyo motor show, complete with a never-to-be-used W18 engine, Bugatti’s fledgling engineering team struggled to bring the key elements together.

-

2000s: Bugatti Veyron 16.4 (cont.)

But in 2003, a new engineering head, Dr Wolfgang Schreiber, was appointed, quickly followed by new president Thomas Bscher.

Almost every aspect of the project was revisited, and by 2005, with an incredible 95% of the car’s components re-engineered, the first Veyron rolled out of Bugatti’s Molsheim works.

However sceptical you were about Volkswagen’s purchase of the historic Bugatti name, it would take a tough cynic to deny that bringing the Veyron to market did justice to marque founder Ettore Bugatti and son Jean, true innovators in their own right and producers of fine automobiles and race cars.

The Veyron really was a technical tour de force like no other.

Now with a W16 engine, it not only produced the requisite 1000hp (actually, 1001PS, or 987bhp), but an eyewatering 922lb ft of torque, which all resulted in an official 253mph.

-

2000s: Bugatti Veyron 16.4 (cont.)

The car’s development had been tortuous.

A total of 10 radiators had to be used to cool the 8-litre engine, which was left without a cover to release still more heat.

In order to deploy all that power, an all-wheel-drive system was created, with a complex Haldex differential working on the front axle and a limited-slip differential at the rear.

A seven-speed dual-clutch automatic gearbox was used, with shift times of just 150 milliseconds.

And the job of hauling nearly two tonnes of Veyron from 250mph to standstill needed carbon-ceramic discs that measured a colossal 15.7in (400mm) in diameter.

-

2000s: Bugatti Veyron 16.4 (cont.)

But it was the Veyron’s W16 engine that gave it the muscle to out-pin the previous decade’s McLaren F1 for maximum velocity.

Created by joining the cylinder banks from two of VW’s narrow-angled VR8 engines on to a single crankshaft (and hence, almost, a ‘W’ shape), a pair of camshafts operated the 32 valves on each eight-cylinder bank.

The engine was square, with each of its 86mm x 86mm cylinders displacing 499.56cc.

Four turbochargers (two per bank) pumped air at 18psi via a pair of charge-cooling liquid-to-air intercoolers, complete with three heat exchangers.

Or, put another way, it was the most extravagant production engine in the world at launch – and the thirstiest: it would take just 20 minutes to empty the Veyron’s 100-litre tank of high-octane fuel at full chat.

-

2000s: Bugatti Veyron 16.4 (cont.)

Having never sat in a Veyron before today, my preconceptions are of a one-dimensional hypercar built for nothing more than achieving 250mph-plus.

That it is nothing of the sort pleases me greatly.

I’m still not a fan of the Veyron’s styling, but when you wonder at the packaging, cooling and aerodynamic challenges faced by Bugatti, it’s remarkable how easy on the eye it actually is.

Step through the driver’s door into the exquisitely trimmed cabin and what strikes you is how conventional and simple all the controls are.

-

2000s: Bugatti Veyron 16.4 (cont.)

I wasn’t expecting a 747’s flight deck, but all that faces you is a small binnacle containing five dials and next to it a machine-turned aluminium console with the climate controls.

Lower down sits the shift lever for the dual-clutch ’box. There’s little else.

I’m not given the ‘magic’ key that permits access to 213mph-plus bedlam, but Jonty Collier from Tom Hartley Jnr, which kindly lent us this Veyron, is not precious about us exploring its potential below that speed.

And I can see why. Push the start button, select drive, accelerate away at a normal rate and you could be driving a slightly larger Golf.

Try a little harder and, incredibly, it’s like a very refined, grown-up Esprit: agile, communicative and responsive during cornering. I drive two laps and comment to Collier that it’s fast but not that fast.

-

2000s: Bugatti Veyron 16.4 (cont.)

He says I need to try harder and wake all four turbos, so I do, and it does.

Speed is always relative, but 40 years of driving some very quick machinery hasn’t prepared me for this.

From inside, the four-blown W16 sounds like that aforementioned 747 on full thrust.

After some initial lag, the Veyron’s 4162lb heft is no match for the monstrous torque, and as we head towards turn one at Prestwold, the speed it reaches is near suicidal.

Thankfully the brakes, helped by the air brake you see springing up in the mirror, are equally stupefying, and we get to live another day.

Well, if not another day, then at least long enough to get a chance to try the Chiron.

Thanks: to Tom Hartley Jnr (tomhartleyjnr.com)

-

2000s: Bugatti Veyron 16.4 (cont.)

Factfile

Sold/number built 2005-’11/252

Engine all-alloy, dohc-per-bank 7993cc W16, with four turbochargers and electronic fuel injection

Max power 987bhp @ 4200rpm

Max torque 922lb ft @ 2200rpm

Transmission seven-speed dual-clutch automatic, all-wheel drive

Suspension independent, by double wishbones, self-damping hydraulics

Steering rack and pinion

Brakes carbon-ceramic discs, with servo and anti-lock

Weight 4162lb (1888kg)

0-60mph 2.5 secs

Top speed 253mph

Price new £925,000 -

2010s: Bugatti Chiron Super Sport 300+

Top speed: 304.8mph

I saw him just the other month. At Donington Park, in the paddock.

He was walking towards me and, keen to get his attention but not remembering his name, all I could think to do was point and say “Fastest man!” as we passed one another.

He smiled back and nodded, and I felt relieved that I wasn’t wrong, despite my cringing approach.

That ‘fastest man’ was Andy Wallace, the Le Mans winner and Bugatti test driver who, in August 2019, drove the aptly named Chiron Super Sport 300+ to 304.77mph at Volkswagen’s Ehra-Lessien test track.

If you followed the story at the time you’ll know that, while 30 Super Sport 300+s were planned (all of which have been sold), the £3.1m model has yet to gain European type approval for its top speed, meaning that the production cars remain limited to 273mph.

-

2010s: Bugatti Chiron Super Sport 300+ (cont.)

So please allow us this small transgression for the sake of our headline figure…

Nonetheless, take any type-approved Chiron – ‘standard’ model, Sport, Pur Sport or Super Sport/300+ – and its only true rival for fastest production car honours in the 2010s and 2020s will be one of its siblings.

No great shock, when the range’s top-speed bandwidth falls between an electronically limited 261 and 273mph.

But let’s start with the original launch model.

Making its debut at Geneva in March 2016, it used the same basic ingredients as the Veyron it succeeded: engine capacity and configuration, transmission and chassis layout all remained unchanged.

However, to cope with the sharp increase in power, the 1184bhp Veyron Super Sport’s engine (from which the Chiron’s is derived) received a stronger crank and conrods.

-

2010s: Bugatti Chiron Super Sport 300+ (cont.)

The size of the four turbochargers was also increased significantly, a move that would normally lead to greater lag under acceleration.

But this was countered cleverly by sending all exhaust gases through two turbos below 3800rpm, then through all four thereafter.

The already hugely capable braking system from the Veyron was upgraded to cope with the Chiron’s even greater top-speed potential.

Disc size was increased by 20mm all round to 420mm (front) and 400mm (rear), controlled by eight- and six-pot calipers respectively.

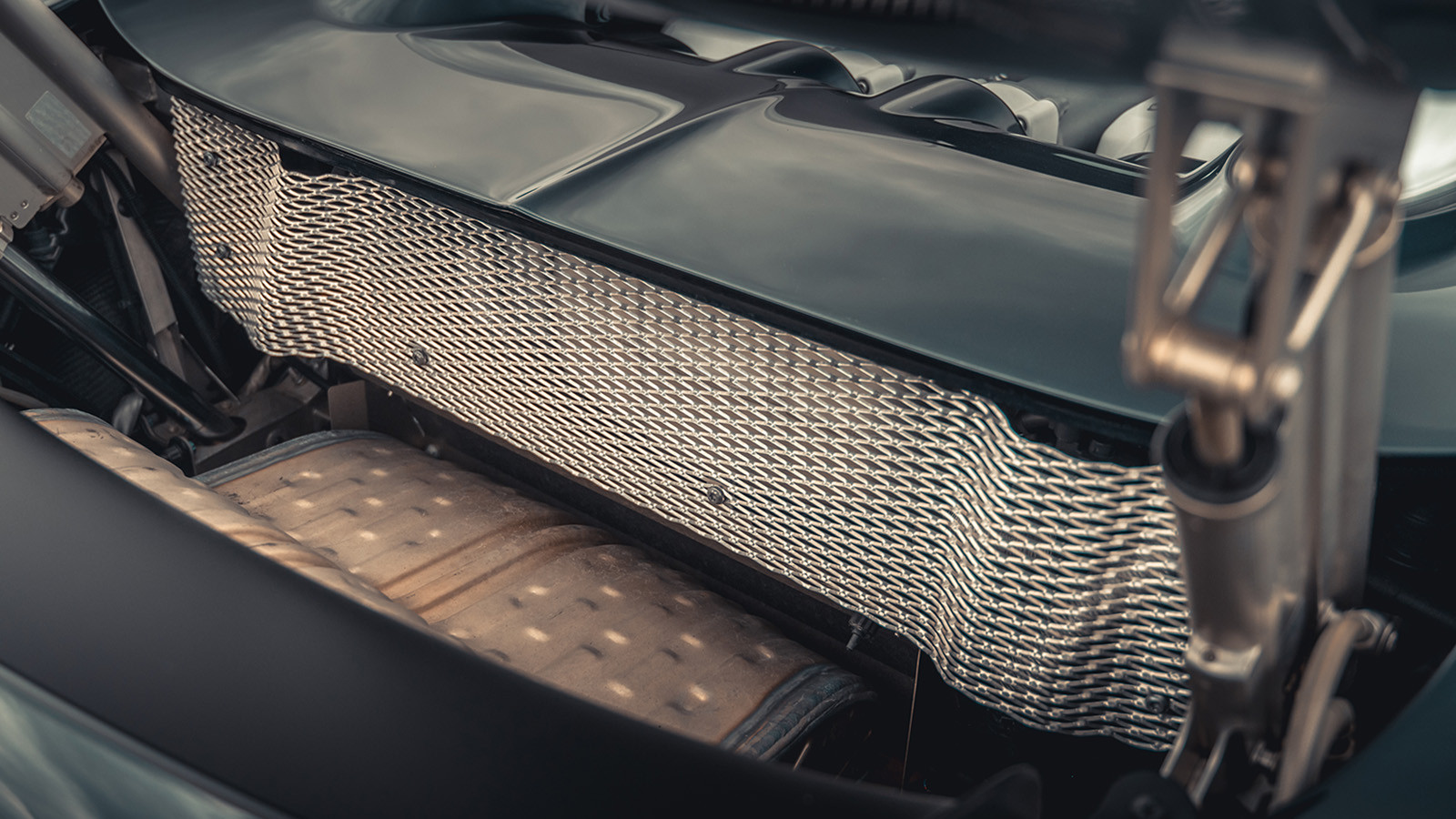

The body itself was markedly different from the Veyron’s, with a large but functional C-shaped scallop arcing from roof to sill and incorporating vital inlets for cooling air to the engine, its carbonfibre construction providing quite staggering torsional rigidity of 50,000Nm per degree and flexural rigidity of 0.25mm per tonne.

-

2010s: Bugatti Chiron Super Sport 300+ (cont.)

Even for those well read in supercar lore, the resultant numbers were extraordinary.

Power rose to 1479bhp at 6700rpm and torque to 1180lb ft between 2000 and 6000rpm – a yet bigger spread than before.

And to illustrate what the Chiron could achieve in extremis, Bugatti employed ex-F1 driver Juan Pablo Montoya to generate some data.

Within a two-mile stretch of Bugatti’s test facility, he accelerated from 0-249mph in 32.6 secs and back to standstill in just 9.4 secs.

Enough? Apparently not, hence the Super Sport 300+ model that gives us our magical maximum.

-

2010s: Bugatti Chiron Super Sport 300+ (cont.)

Developed by Bugatti’s head of exterior design, Frank Heyl, in conjunction with Michelin and engineering firm Dallara, the Chiron adopted a 9.8in-longer rear end for better aerodynamics, a power boost to 1578bhp, a narrower rear wing and a drag-reducing, laser-controlled ride-height system.

Crucially, Wallace’s record car had no limiter but was fitted with a full rollcage and myriad test equipment during the top-speed attempt.

Our test Chiron is a mere ‘standard’ model, and again I haven’t been given ‘the key’ that releases its full majesty.

But it would be pointless at Prestwold, anyway.

-

2010s: Bugatti Chiron Super Sport 300+ (cont.)

Ahead is one of the most elegant airbag-equipped steering wheels I’ve seen. Ferrari Manettino-style controls sprout from under its spokes, and a launch switch sits below the leather-trimmed hub.

The centre console, like the Veyron’s, remains simplicity itself but is far narrower, still holding the heater controls and a shifter for the dual-clutch auto ’box.

You already know I’m going to tell you the Chiron is fast, but with 500bhp more than the already bombastic Veyron, normal superlatives simply don’t do it justice.

We make three, full-bore rolling starts from 30mph: the rear wheels scrabble slightly and, manually shifting the gears, we nudge 150mph each time before having to brake hard for corners (damn those corners).

-

2010s: Bugatti Chiron Super Sport 300+ (cont.)

Objectively, engaging all four turbos is so much easier than in the Veyron, with a commensurate lift in low-end performance that is by any measure stratospheric.

It’s the sheer lack of drama with which the Chiron goes about its business that impresses most, though: unrelenting, mesmerising, frightening amounts of power are deployed with an almost serene mechanical indifference.

Is our story’s final Vmax legend the pinnacle of combustion-engined brilliance, or the last bastion of automotive profligacy?

I fear the answer to that question is probably both.

Thanks to: Tom Hartley Jnr (tomhartleyjnr.com)

-

2010s: Bugatti Chiron Super Sport 300+ (cont.)

Factfile

Sold/number built 2019-date/30

Engine all-alloy, dohc-per-bank 7993cc W16, with four turbochargers and electronic fuel injection

Max power 1578bhp @ 4200rpm

Max torque n/a

Transmission seven-speed dual-clutch automatic, all-wheel drive

Suspension independent, by double wishbones, self-damping hydraulics

Steering rack and pinion

Brakes carbon-ceramic discs, with servo and anti-lock

Weight n/a

0-60mph 2.3 secs

Top speed 304.8mph

Price new £3.1m