-

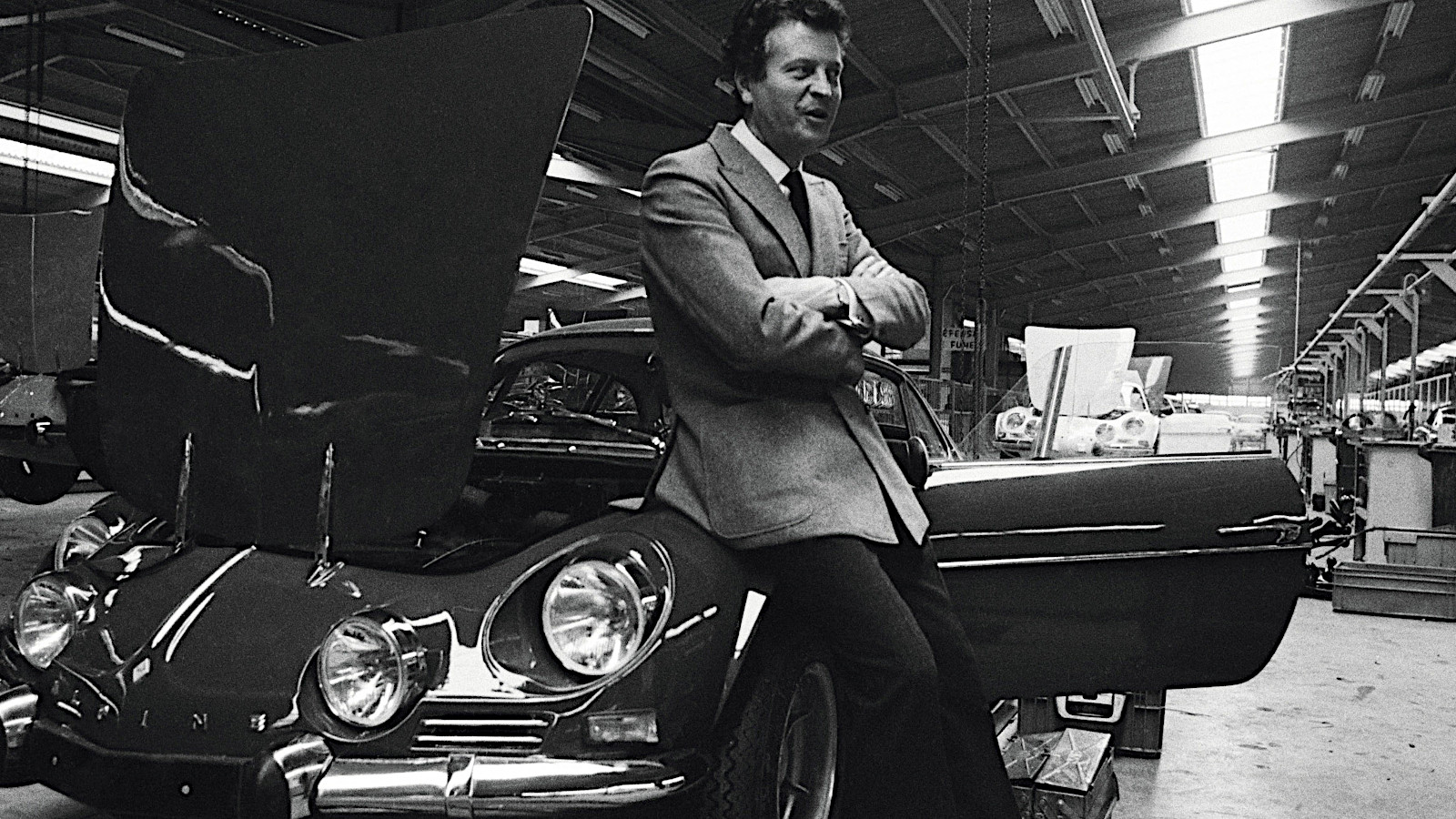

© Tony Baker/Classic & Sports Car

© Tony Baker/Classic & Sports Car -

© Alpine

© Alpine -

© Renault

© Renault -

© Alpine

© Alpine -

© Alpine

© Alpine -

© Alpine

© Alpine -

© Renault

© Renault -

© Alpine

© Alpine -

© Alpine

© Alpine -

© Tony Baker/Classic & Sports Car

© Tony Baker/Classic & Sports Car -

© Alpine

© Alpine -

© Renault

© Renault -

© Alpine

© Alpine -

© Alpine

© Alpine -

© Alpine

© Alpine -

© Tony Baker/Classic & Sports Car

© Tony Baker/Classic & Sports Car -

© Tony Baker/Classic & Sports Car

© Tony Baker/Classic & Sports Car -

© Tony Baker/Classic & Sports Car

© Tony Baker/Classic & Sports Car -

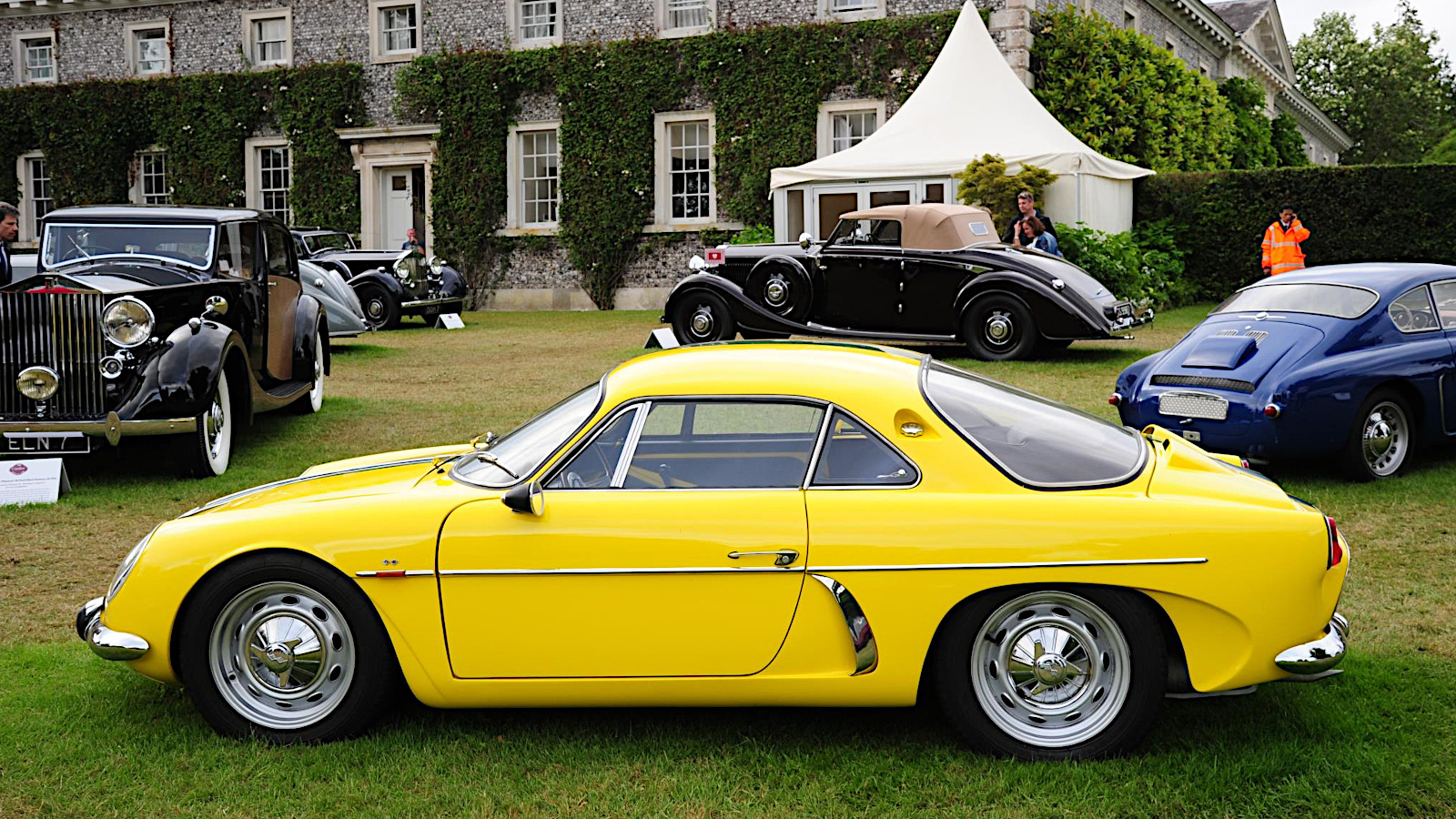

© Lothar Spurzem/Creative Commons https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/de/legalcode

© Lothar Spurzem/Creative Commons https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/de/legalcode -

© Alpine

© Alpine -

© Renault

© Renault -

© Alpine

© Alpine

-

Success story

Even if the highly praised modern version had never existed, the original A110 would still be known for being the first truly successful Alpine model, perhaps the prettiest and undoubtedly the first to achieve global success in motorsport.

As confirmed by the brand’s current owner, Renault, the A110 was introduced in 1962, though other years are sometimes quoted.

So 2022 is therefore the model’s 60th anniversary, so this is a good time to revisit the car and recall the process that led to it.

-

Monsieur Alpine

Alpine was created by Jean Rédélé, the eldest son of Émile Rédélé, who had worked for Renault before setting up a dealership for the marque in Dieppe, on France’s Normandy coast, in the 1920s.

Badly damaged in the Second World War, the dealership was subsequently rebuilt, with Jean in charge.

As well as running a successful business, Jean was a talented sailor and a successful competition driver. He also developed the skills to build his own cars, and naturally used Renault components rather than inventing his own.

-

The Renault 4CV

Every Alpine in history dates back to Renault’s first post-war model. The 4CV (sold in the UK as the 750) was a small sedan powered by a remarkably smooth-running little engine known as the Billancourt, after Renault’s factory in Paris.

Rédélé began his motorsport career in a 4CV. In July 1954, he finished second overall in the Alpine Rally, and was awarded a Coupe des Alpes for completing the event without time penalties.

The Alpine brand was created 11 months later. “I thoroughly enjoyed crossing the Alps in my Renault 4CV, and that gave me the idea of calling my future cars ‘Alpines’,” Rédélé explained. “It was important to me that my customers experienced that same driving pleasure at the wheel of the car I wanted to build.”

-

The Alpine A106

The first Alpine was essentially a 4CV with a fastback fiberglass body, though convertible and coupe derivatives would appear later.

The 106 part of its name was part of several four-letter codes used by Renault for the 4CV.

A106s were driven in several big-name events including the Mille Miglia road race. Remarkably for the 1950s, one of the high-performance options was a five-speed gearbox.

-

The Alpine A108

The A106 was gradually replaced by the A108, which again used Renault’s Billancourt engine.

Introduced in 1958, it became available two years later with a backbone chassis under the fiberglass body.

-

The Brazilian A108

The car pictured here is not, strictly speaking, an Alpine A108, but was built in Brazil and marketed there as the Willys Interlagos.

US company Willys-Overland had started manufacturing cars in Brazil during the 1950s, and also built the Renault Dauphine there under license.

The Interlagos was a popular car among Brazilian racing drivers, the most famous being future double Formula One World Champion Emerson Fittipaldi.

-

The Cléon-Fonte engine

The body/chassis arrangement and the general styling of the Alpine A108 were nearly enough to lead to the creation of the A110. The only piece missing from the jigsaw was the engine.

In 1962, Renault launched a new motor which is usually referred to as the Cléon-Fonte, though it was also known as the C-Engine or Sierra.

Larger and more powerful than the Billancourt, it became available in the Floride/Caravalle roadster and Estafette van ranges. Later in the same year, it was also used in the Renault 8 (pictured in Gordini form), the first car designed from scratch to be fitted with it.

The Cléon-Fonte would remain in production until 2004, when it was still being used by Dacia – 42 years earlier, it was the first engine used in the A110.

-

A110 debut

Powered by the Cléon-Fonte engine, and with styling differing only in detail from that of the A108, the A110 quickly became by far Alpine’s most successful car to date.

Total production of the A106 and A108 had not quite reached 500 units. According to its own figures, Alpine would eventually build over 7500 A110s.

-

Foreign A110s

Versions of the A110 were built outside France. The only one sold under the same name was manufactured in Valladolid, Spain, by FASA, which had started out making 4CVs under license and later became a subsidiary in Renault.

In Mexico, truck and bus manufacturer Diesel Nacional produced its own version called the Dinalpin, while in Bulgaria the company responsible for building Bulgarrenaults (locally produced Renault 8s and 10s) also marketed the Bulgaralpine A110 clone.

Between them, FASA and Diesel Nacional built around 2600 A110s. Alpine’s own figure for the Bulgaralpine is 50 units, though wildly different numbers are quoted by other sources.

-

The A110 GT4

The GT4 is possibly the least well remembered car in the A110 range.

It was a long-wheelbase coupe with 2+2 seating, the replacement for a version of the A108 with a similar layout.

More practical than the regular A110, it also looked far less appealing. Perhaps for that reason, only 112 were built in two years.

-

The A110 convertible

Alpine created a two-seat convertible derivative of the A110 for customers who preferred open-air motoring.

As with the GT4, a considerable amount of the coupe’s beauty was lost during the transformation. The car is now very rare.

-

The Cléon-Alu engine

The Cléon-Fonte engine was available in capacities ranging from 1.0 to 1.4 liters, and could exceed 100HP in its wildest form.

This figure was obliterated by another Renault engine which became available in the A110 in the late 1960s. The Cléon-Alu, which made its debut in the Renault 16 (pictured), was built in the same factory, but was larger and had an aluminum block.

It started out at 1.5 liters, in which form it was also fitted to the Lotus Europa before Lotus switched to its own Ford Kent-based Twin Cam engine. Larger and more powerful versions would soon be added.

-

Rallying

With their lack of weight, low center of gravity and aerodynamic shape, the French A110 and the Bulgaralpine equivalent were very competitive in rallying even when powered by the little Cléon-Fonte engine.

The introduction of the Cléon-Alu transformed the car and rocked the sport. With far more power available, the A110 could now beat almost every other contender.

-

The hammer throw

Rallying an A110 was not without its challenges, as drivers more used to front-engined cars soon found out.

With a relatively heavy engine mounted behind the rear axle, the Alpine could be tricky to handle. Even the supremely talented Andrew Cowan, who finished fifth in an A110 in the snowy 1970 RAC Rally, described the experience to my father as being “like throwing a hammer backwards”.

Nevertheless, the combined ability of the car on various surfaces allowed it to dominate the rallying world for several years.

-

The International Championship for Manufacturers

In the three seasons before the creation of the World Rally Championship, there was a series called the International Championship for Manufacturers.

Despite a late-season charge, Alpine was unable to overcome Porsche’s early advantage in 1970, and finished two points behind in second place.

The following year, Alpine was in complete control, finishing the season with double the points of second-placed Saab.

The A110 appeared in the ICM only sporadically during 1972, but even greater success was to follow very shortly.

-

World domination

Almost every A110 fan will be aware of Alpine’s spectacular performance in 1973, the first year of the World Rally Championship.

The season began explosively when A110s finished first, second, third, fifth, sixth and 10th in Monte-Carlo. There was another one-two-three at the end of the year in Corsica, and several wins and podium positions in between.

The other manufacturers simply couldn’t keep up. Using technology taken from everyday Renaults, Alpine scored 147 points. Fiat, using its 124 Abarth Rallye, was a distant second on 84 points, while Ford could manage only 76 with the Cosworth BDA-engined Escort RS 1600.

-

No champion driver

The World Championship for Drivers was not established until 1979. If it had existed six years earlier, an Alpine driver would almost certainly have won it.

At first sight, Jean-Luc Thérier was the most successful A110 driver that season, winning three WRC rounds.

Jean-Claude Andruet and Jean-Pierre Nicolas won one each, but Nicolas finished more events than any other Alpine driver. By the scoring system used in 1979, he would have lost out to Thérier only on a tie-break.

-

National success

1973 was Alpine’s glory year in rallying, but the A110 already had a tremendous reputation as a competition car before then.

From 1967 onwards, it won national championships in Bulgaria, France, Spain, Romania and the country formerly known as Czechoslovakia.

In the UK and the Nordic countries, where rallying took place predominantly on gravel roads, the A110 was less popular. British drivers in particular would have taken a lot of persuading to choose the little French sports car over the almost completely dominant Ford Escort.

-

Changing times

Even in the year of its greatest triumph, the A110 was starting to fade away.

Alpine had already introduced its new A310 (available first with the Cléon-Alu engine and later with the 2.7-liter Douvrin V6 fitted to the Renault 30) and was about to be taken over by Renault.

Its next great motorsport triumph would come in 1978, when the turbocharged Alpine A442 won the Le Mans 24 Hour race.

The Le Mans victory came a year after A110 production finally ended. By almost any standards, the car had had a good run over a decade and a half.

-

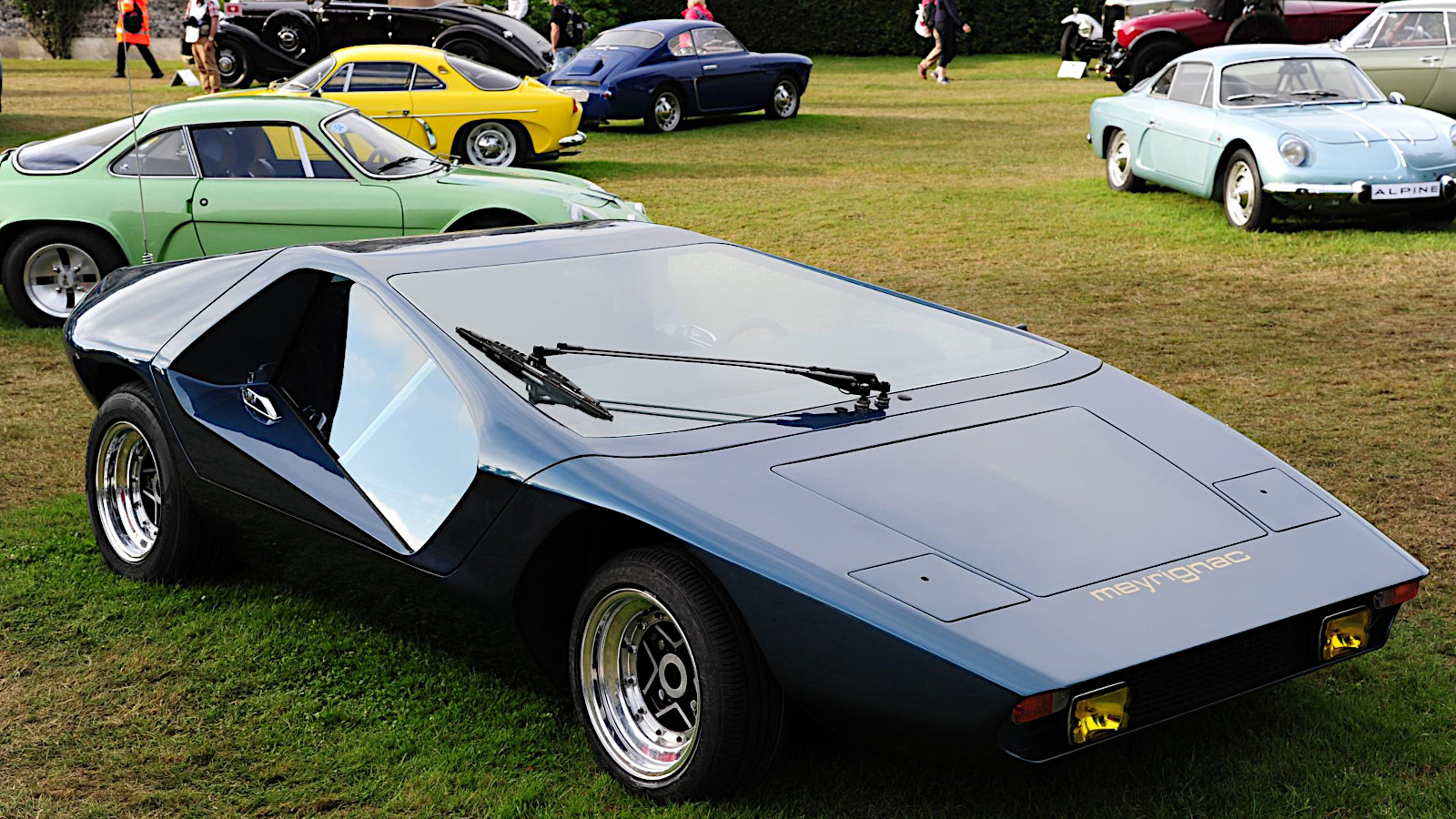

The Meyrignac car

Right at the end of the A110’s life, a very special derivative was displayed at the 1977 Geneva show.

The wedge-shaped creation was the work of a young designer called Denis Meyrignac, who had been given an A110 chassis and running gear. (The car is sometimes said to have been based on an A310, but the evidence does not support this.)

It was in storage for many years, but Meyrignac has since restored it himself. It appeared at Goodwood in 2016.

-

The Alpine A110-50

Renault celebrated the half-century of the A110 by creating a concept racing car called the A110-50.

Closely related to the Renault Sport Megane Trophy racer, the A110-50 had an unsilenced 3.5-liter V6 (mounted ahead of the rear axle rather than behind it), and a carbonfiber body vaguely resembling the fiberglass one of the original car.

It made its debut on the Monaco Grand Prix circuit in May 2012, and was well received. More importantly, it offered a hint that a new A110 production car might come along in the near future.

-

The new A110

Sure enough, the second-generation A110 was introduced in 2017. Powered by a turbocharged 1.8-liter engine, it resembles the original far more than the A110-50 did.

Like its predecessor, it also relies partly on low weight for its performance and handling, though the engine is more than adequately powerful for the job.

Once again, that engine is mounted within the wheelbase, and the car is largely constructed of aluminum. In its basic concept, though, it can reasonably be thought of as a true 21st-century successor to the car Jean Rédélé and his team came up with back in 1962.