-

© Ford

© Ford -

© Joe deSousa/Creative Commons licence https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/legalcode

© Joe deSousa/Creative Commons licence https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/legalcode -

© National Library of France/Creative Commons https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode

© National Library of France/Creative Commons https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode -

© Public domain

© Public domain -

© Franz Haag/Creative Commons licence https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/legalcode

© Franz Haag/Creative Commons licence https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/legalcode -

© Public domain

© Public domain -

© Concours Virtual

© Concours Virtual -

© Public domain

© Public domain -

© Owen Fitter/RM Sotheby’s

© Owen Fitter/RM Sotheby’s -

© Porsche

© Porsche -

© Gabor Mayer/RM Auctions

© Gabor Mayer/RM Auctions -

© Alexander Migl/Creative Commons licence https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode

© Alexander Migl/Creative Commons licence https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode -

© RM Sotheby’s

© RM Sotheby’s -

© Krzysztof Marek Wlodarczyk/Creative Commons licence https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode

© Krzysztof Marek Wlodarczyk/Creative Commons licence https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode -

© Bonhams | Cars

© Bonhams | Cars -

© US Library of Congress/public domain

© US Library of Congress/public domain -

© Darin Schnabel/RM Auctions

© Darin Schnabel/RM Auctions -

© NAParish/Creative Commons licence https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/legalcode

© NAParish/Creative Commons licence https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/legalcode -

© Stellantis

© Stellantis -

© Škoda

© Škoda -

© Lizzie Pope/Classic & Sports Car

© Lizzie Pope/Classic & Sports Car -

© Stellantis

© Stellantis -

© Daimler AG

© Daimler AG -

© Ford

© Ford -

© Tony Baker/Classic & Sports Car

© Tony Baker/Classic & Sports Car -

© Stellantis

© Stellantis -

© DeFacto/Creative Commons licence https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/legalcode

© DeFacto/Creative Commons licence https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/legalcode -

© AxelHH/Public domain

© AxelHH/Public domain -

© Tammy Thompson/Auctions America

© Tammy Thompson/Auctions America -

© Mecum Auctions

© Mecum Auctions -

© Dave Scott, NASA/Public domain

© Dave Scott, NASA/Public domain -

© Constantine Adraktas/Creative Commons https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/legalcode

© Constantine Adraktas/Creative Commons https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/legalcode -

© RM Sotheby’s

© RM Sotheby’s -

© Saab

© Saab -

© Ferenghi/Creative Commons licence https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/legalcode

© Ferenghi/Creative Commons licence https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/legalcode -

© AJB83/Public domain

© AJB83/Public domain -

© Leonard G./Creative Commons licence https://creativecommons.org/licenses/sa/1.0/legalcode

© Leonard G./Creative Commons licence https://creativecommons.org/licenses/sa/1.0/legalcode -

© GM

© GM -

© EVplus/Public domain

© EVplus/Public domain -

© Ford

© Ford -

© Peter Turvey/Creative Commons licence https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/legalcode

© Peter Turvey/Creative Commons licence https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/legalcode

-

Thinking outside the box

Although we’re now well into the electric-motoring revolution, it’s still the case that most of the cars built so far have been powered by internal-combustion engines fueled either by gasoline or by diesel.

These, however, are not the only options, and inventive minds within the automotive industry have explored other possibilities across the decades, too.

Here are 40 examples, all of which – with one notable and justifiable exception – were up and running before the year 2000, presented in chronological order.

-

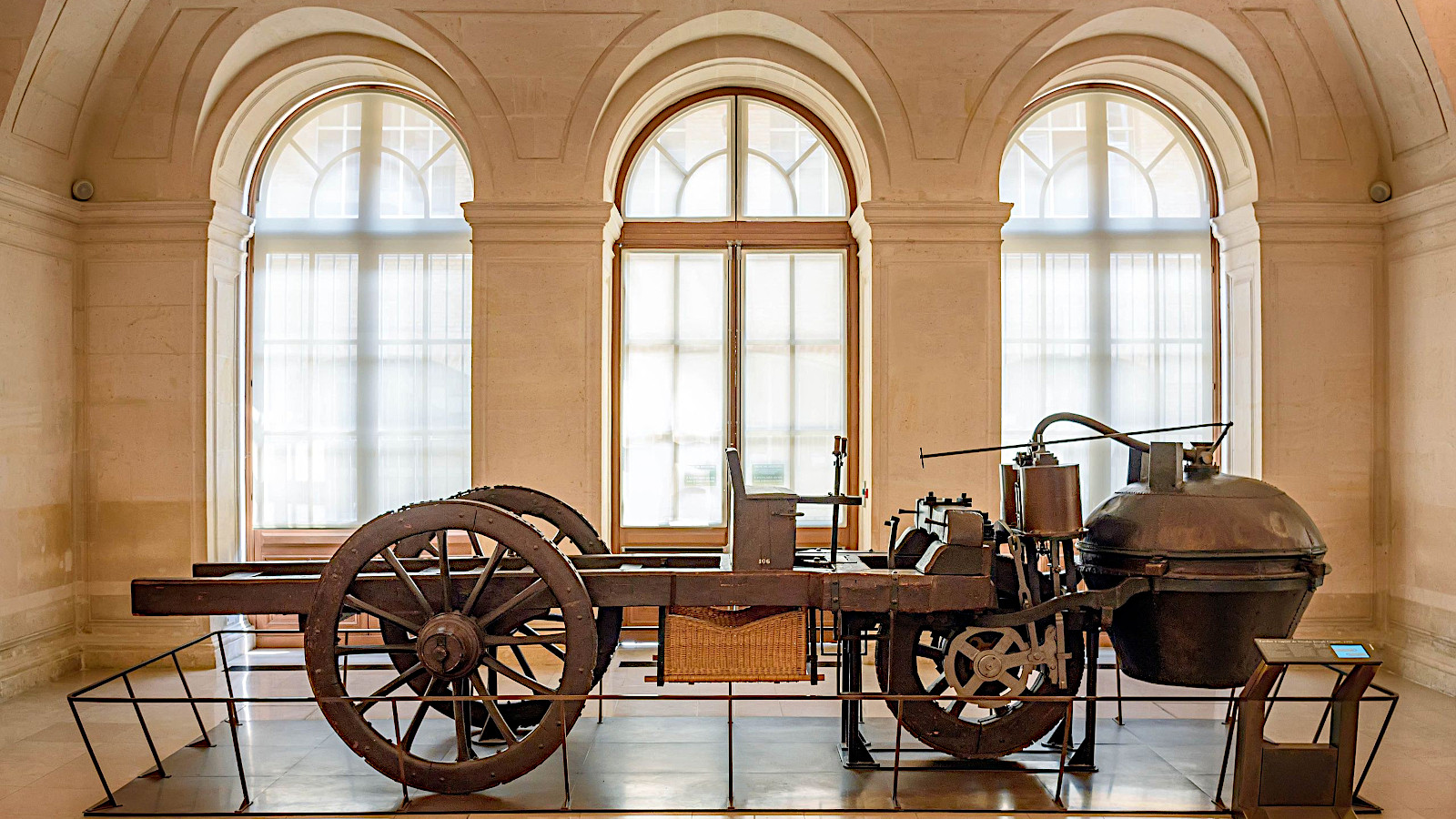

1. Cugnot (1770)

The Benz Patent Motorwagen is often credited as being the first automobile, but there’s a case for saying that the credit should actually go to Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot’s fardier à vapeur.

This steam-powered device was never put into production, but it was a self-propelled vehicle which could carry passengers, which makes it sound like a car to us.

With a boiler mounted ahead of the single front wheel, the fardier must have had very heavy steering, and would probably have suffered from pretty serious understeer if it could travel much faster than walking pace, which reports suggest it couldn’t.

-

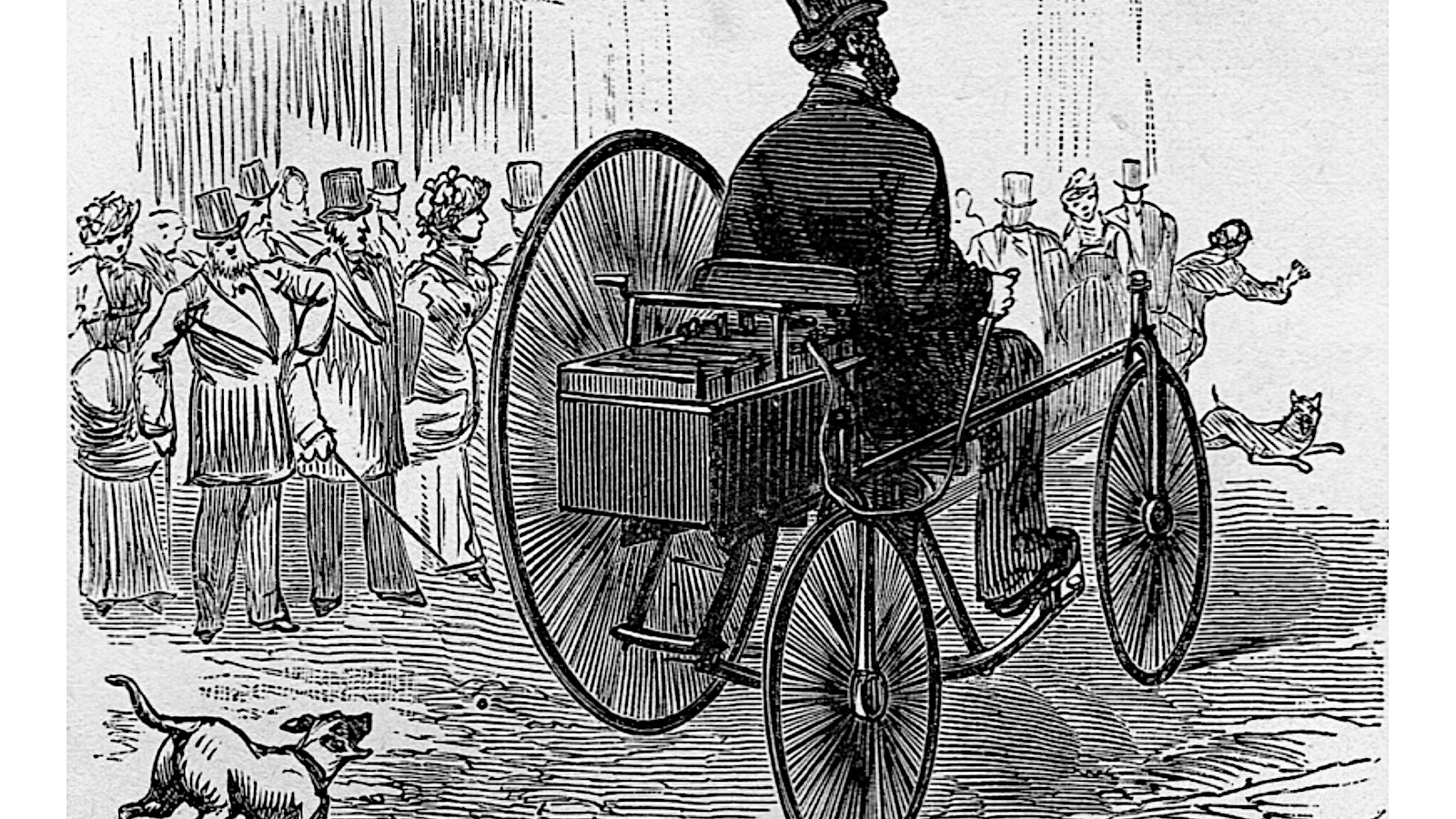

2. Trouvé (1881)

French engineer Gustave Trouvé spent the second half of the 19th century electrifying almost everything he could lay his hands on.

In 1881, he added an electric motor to a tricycle.

Now considered by some to be the world’s first electric road vehicle (although this ignores, for example, Robert Anderson’s work in the 1830s), it was tested along the Rue de Valois in Paris.

A whole 140 years later, at the request of Jeremy Hart and with funding from Maxus, Christian Richards built a replica of the Trouvé and drove it along the same street.

-

3. Elwell-Parker (approx. 1884)

In 1882, Thomas Parker, who might be described as the Gustave Trouvé of Britain’s West Midlands, set up in business with Paul Elwell to build batteries and dynamos.

At some point shortly after that, they began building electric cars, though it’s difficult to determine if these were, as has been claimed, put into what could reasonably be called production.

Like Trouvé’s tricycle, the Elwell-Parkers were an interesting but short-lived distraction.

That said, at least one of them seems to have been quite robust, since the picture here is believed to have been taken in 1895, when the car shown must have been around 10 years old.

-

4. Flocken Elektrowagen (1888)

Andreas Flocken built what is inevitably, but wrongly, described as the world’s first electric car in Coburg, Germany, in 1888.

Clearly of the horseless-carriage type, that automobile was followed by some others (the exact number is unclear) until 1903.

Much later, Franz Haag created a reconstruction (pictured) of the original model, which was displayed at the Retro Classics event in Stuttgart in 2011.

Haag subsequently developed an EV of his own – which he described as “a further development of the scooter and quad” rather than a car – and called it the Flocken Urbano.

-

5. Cederholm (1892)

Despite the increasing popularity of electricity and gasoline, the Cederholm brothers of Ystad chose steam for what was probably the first, and is certainly the oldest-surviving, car built in Sweden.

By several modern accounts, it was badly damaged in a crash, but the Cederholms made a better one (pictured) in 1894 using some of the salvaged parts.

This car was displayed for several years in the Johanna Museum just outside Skurup, but has since been moved to the Military History Museum back in Ystad.

The two venues are approximately 15 miles apart, a distance the Cederholm would probably have taken more than an hour to cover under its own power.

-

6. Salvesen (1893)

Henry Salvesen was a Scottish engineer of Norwegian descent, and a member of the family which owned the Christian Salvesen transport company.

In 1893, he built a steam car in Grangemouth, on the southern bank of the River Forth and only a few miles from Bo’ness, where the first round of the British Hillclimb Championship was held 54 years later.

The steamer still exists, and is not simply stored in a museum but used regularly.

Its fourth and current owner is Duncan Pittaway, whose other cars include the mighty Fiat S76, otherwise known as the Beast of Turin.

-

7. Riker (1896)

The Horseless Carriage race held at Narragansett Park near Providence, Rhode Island, in 1896 had to be abandoned due to a storm after only two heats had been run, so the organizers decided to award first prize to the driver of the car which had covered a measured mile in the least time.

Andrew Riker, of the Brooklyn-based Riker Electric Motor Company, therefore pocketed $900 (the equivalent of around $33,000 today) after completing that distance in 2 min 13 secs, an average of 27mph.

In its report of the event, Scientific American magazine made a prophetic comment: “The electric carriage has made a record for speed, and the great ease of control and the absence of noise and odor will commend it to those who are anxious to purchase horseless carriages, but whether they are adapted for long runs or not still remains to be proved.”

Riker began selling electric cars and trucks to the public the following year, but soon switched his attention to the internal-combustion engine.

-

8. Stanley (1897)

Twin brothers Frances and Freelan Stanley abandoned their successful careers in manufacturing photographic plates and began building steam cars in 1897.

Early highlights included a spectacular demonstration in Boston in 1898 and Freeman’s drive, along with his wife Flora, to the top of Mount Washington, New Hampshire, the following year.

In 1906, the Stanley Rocket driven by Fred Marriott became the second and last steamer to break the Land Speed Record with a run at 127.66mph, a performance not exceeded by any other steam car for the next 103 years.

Remarkably, Stanley remained in business until as late as 1924, though by that time its cars had become far less appealing than those powered by gasoline engines.

-

9. Egger-Lohner C.2 Phaeton (1898)

After several decades as a carriage maker, Lohner had the notion, near the end of the 19th century, to build vehicles which did not have to be pulled by horses.

The first was the Egger-Lohner C.2 Phaeton, whose power source was an electric motor.

Ferdinand Porsche, then in his early 20s, was involved in its design, and this – along with the appearance of the code P1 on parts of the only-surviving model – led to the suggestion that it can be described as the first Porsche automobile.

This has been vigorously disputed, but the C.2 Phaeton is certainly a very early example of a German electric vehicle, though predated by the Flocken Elektrowagen.

-

10. Baker Electric (1899)

Baker Electric built its first car in 1899, and merged with Rauch and Lang in 1915.

Between those years, it was one of the most successful auto makers in the US, and attracted customers such as Chulalongkorn (king of what was then known internationally as Siam but is now called Thailand) and Thomas Edison.

In 1909, President William Howard Taft chose a Baker Electric as one of the first four cars in the White House fleet.

This was replaced by a 1912 model which was driven by First Ladies Helen Taft, Ellen Wilson, Edith Wilson, Florence Harding and Grace Coolidge until 1928.

-

11. La Jamais Contente (1899)

From December 1898 to April 1899, the Land Speed Record was first set and then broken five times on a road near Achères, north-east of Paris, in various electric vehicles.

The affair was finally settled when Belgium’s Camille Jenatzy achieved 65.79mph on La Jamais Contente (‘the never satisfied’).

Seven months later, Jenatzy won an event at Chanteloup-les-Vignes, just across the River Seine.

This double achievement made Jenatzy and his bullet-shaped machine (replica pictured) the first and, it seems safe to assume, the last Land Speed Record driver/car combination to set the best time overall in a hillclimb.

-

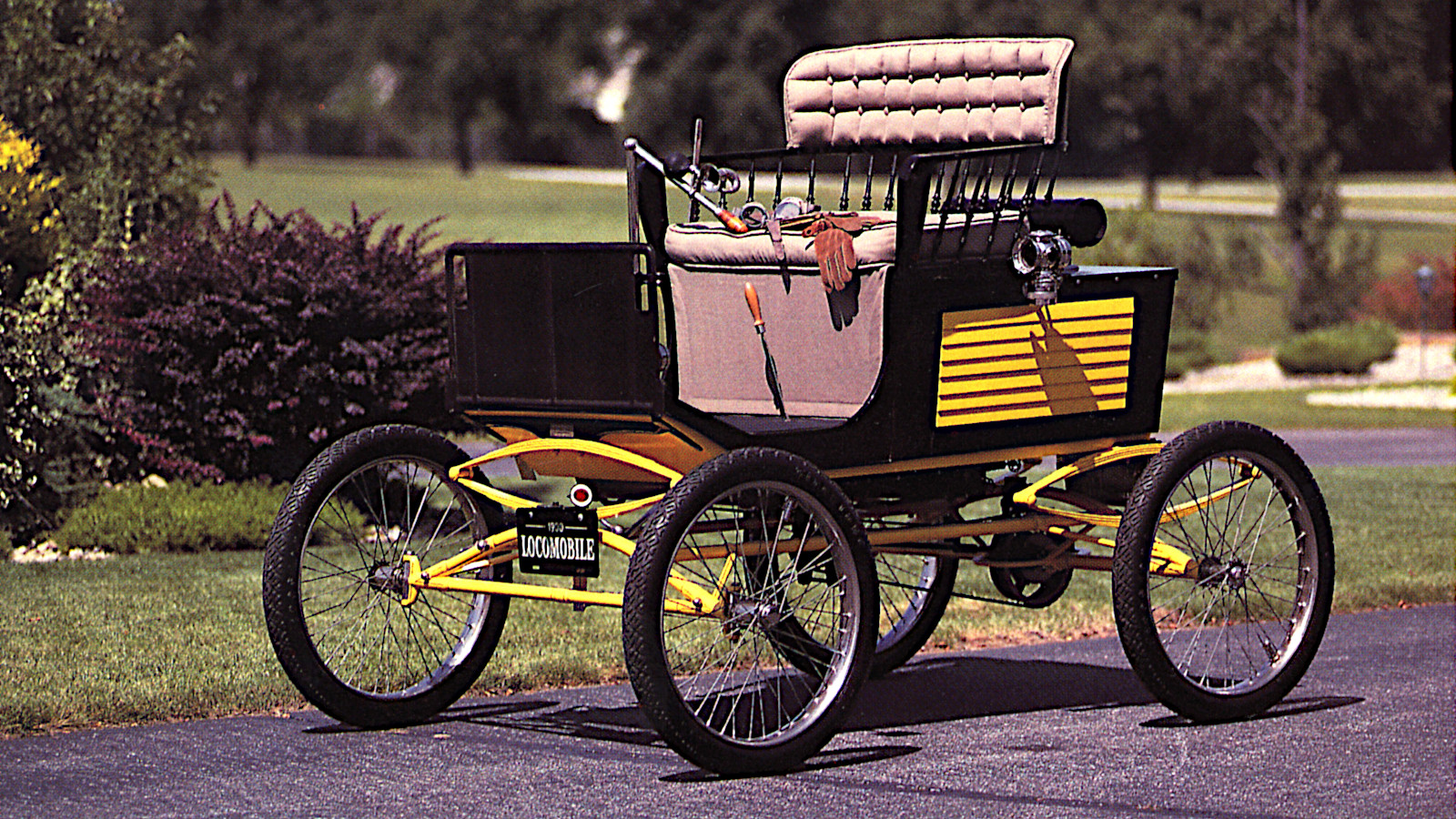

12. Locomobile (1899)

Locomobile’s first steam car was built to a design by the Stanley brothers, and was referred to in an 1899 advertisement (which also suggested that the car offered an ‘exhilarating sense of freedom and power’) as the Stanley Locomobile.

The Stanleys, who had sold their original car company in the same year Locomobile was created, established another one in 1902, and therefore became rivals rather than helpers.

Perhaps not coincidentally, Locomobile abandoned steam not long afterwards, and in 1904 marketed its first model with an internal-combustion engine, which had been designed by the previously mentioned Andrew Riker.

In an odd twist of fate, one of the pioneers of American electric cars was therefore largely responsible for one of the earliest manufacturers of American steamers deciding that building cars powered by gasoline was the way forward.

-

13. Gardner-Serpollet (1900)

French brothers Leon and Henri Serpollet had already been building steam cars under their own name for some time when they met an American investor called Frank Gardiner, with whom they formed the Gardner-Serpollet company in 1900.

The firm produced roadgoing steamers until Leon’s death in 1907, but is perhaps best remembered now for its competition cars, especially one known, because of its oval body, as the Œuf de Pâques, or Easter Egg.

In April 1902, with Leon at the wheel, the Œuf de Pâques became the first non-electric car to set a Land Speed Record, and the second car and last car of any type, after La Jamais Contente, to do so in the same year as winning a hillclimb – or in this case two, both held at Gaillon.

Unlike its electric rival, the Œuf de Pâques achieved this with different drivers.

On both occasions at Gaillon, it was driven by Hubert le Blon (who in 1910 became the sixth person ever to die in an air crash) with his wife Motan acting, as she usually did, as riding mechanic.

-

14. Toledo (1900)

The short-lived but very ambitious American Bicycle Company produced more types of vehicle than its name suggested.

These included a steam car which was designed by Frederick Billings and made its debut at the first New York Auto Show in November 1900.

The car became known as Toledo, and was later produced by the International Motor Company.

It was the predecessor of the cars built by Albert Pope’s Pope-Toledo brand, all of which had gasoline engines.

-

15. White (1900)

Massachusetts-based White built cars from 1900 to 1918, and relied entirely on steam power for the first decade.

The marque gained a lot of publicity from its very fast and extraordinarily low-slung Whistling Billy, which began winning races and setting speed records in 1905.

In complete contrast, William Howard Taft included the White Model M pictured here (along with the Baker Electric mentioned earlier and two Pierce-Arrows) in the first US Presidential car fleet, and was said to be pleased that he could use it to envelop snooping photographers in a cloud of steam.

White built its last steamer in 1911, and its last car of any sort seven years later.

-

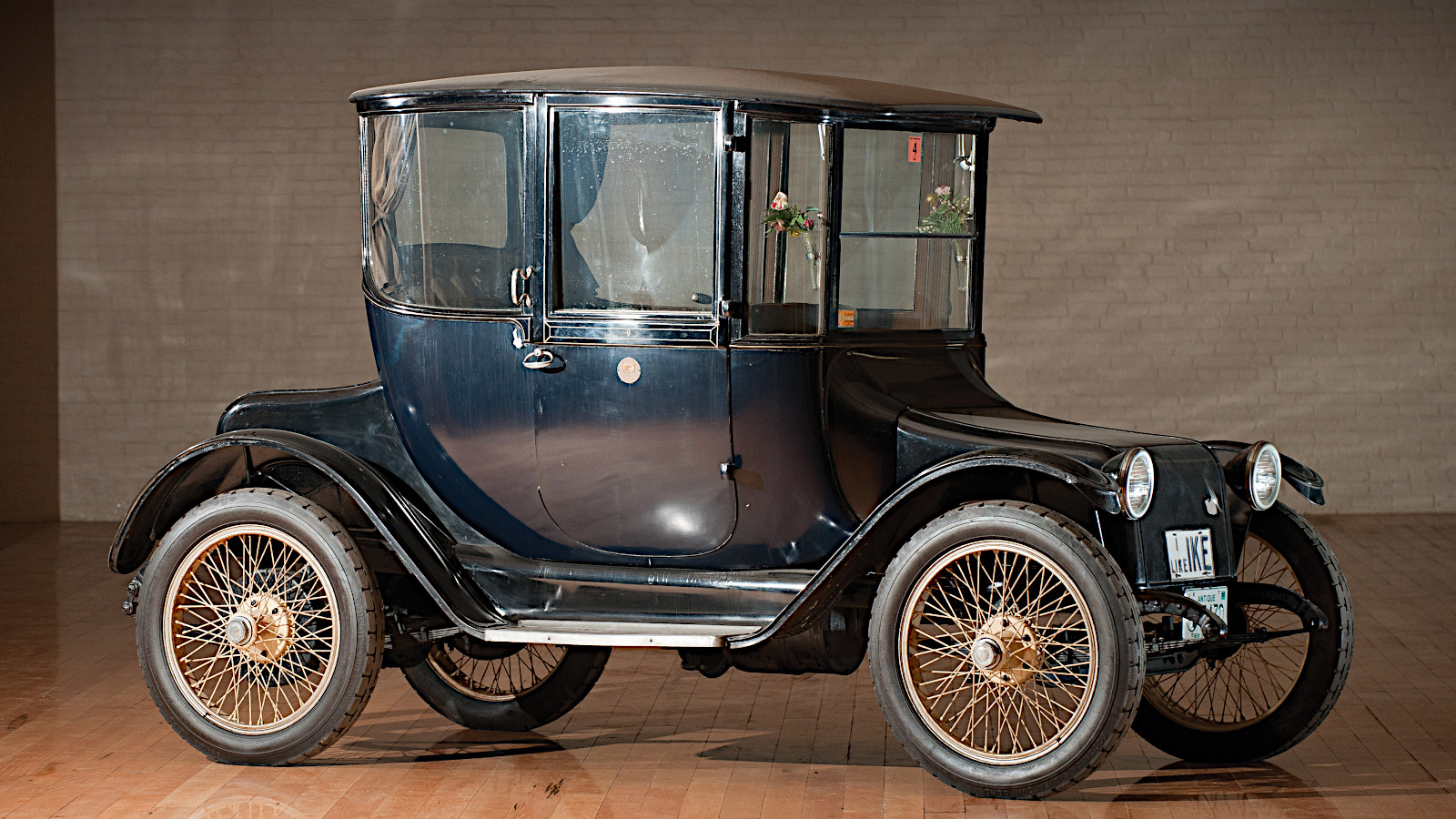

16. Detroit Electric (1907)

With their modest performance and very tall bodies, the early Detroit Electrics would not have been suitable for the open road, but they were ideal for driving in towns and cities.

As with all EVs of the period, their appeal dropped considerably when self starters made it unnecessary for people to risk injury by using a handle to fire up their gasoline-engined cars.

Detroit Electric does not appear to have noticed this, and continued along the same lines for an incredibly long period.

The final versions, with more conventional bodies, were built as late as 1939, though by that time very few people were interested in them.

-

17. Doble (1909)

Like Detroit Electric, Doble stuck to its original plan many years after most manufacturers had committed themselves to the internal-combustion engine.

The first Doble went on sale in 1909, and by the 1920s the company was producing refined, elegant and dazzlingly expensive cars (such as the 1924 Model E pictured here) powered by steam.

Doble also built steam engines for use in other vehicles including locomotives, trucks and, during the First World War, a prototype tank.

All activities ceased when the company folded in 1931.

-

18. Opel-RAK (1928)

As well as working for the auto maker established by his grandfather, Fritz von Opel was a successful racer of both cars and powerboats, and a pioneer in rocketry.

His rocket-propelled vehicles, known as Opel-RAK, included an airplane, a motorcycle, two rail vehicles and two cars.

The first car, RAK 1, was a proof of concept and not particularly fast, but RAK 2 (pictured) had 24 rockets with a combined thrust of six tonnes, and was timed at 148mph on the Avus race track near Berlin in 1928, with 3000 awed spectators in attendance.

‘Rocket Fritz’ said later that he was “acting on instinct alone, with uncontrollable forces raging behind me”, which should make us grateful that he never built a roadgoing version.

-

19. Škoda truck (1938)

Škoda’s first EV was a truck designed for the noble purpose of transporting beer from the famous brewery in the Czech city of Pilsen to local restaurants.

Although it presumably couldn’t travel very quickly, it had a surprisingly aerodynamic cab, at least by the standard of the late 1930s.

The electric motor was mounted directly beneath this, while the vehicle had, according to Škoda, a payload of between 1.5 and three tonnes.

Škoda followed this in the early 1940s with an electric toy car, but it did not put another roadgoing vehicle of this type on sale until it introduced the Eletra 151 variant of the Favorit hatchback half a century later.

-

20. Peugeot 402 (1940)

Believing, correctly, that gasoline might be in short supply as the Second World War progressed, Peugeot converted the 2142cc engine of its 402 sedan so that it could run on charcoal.

The rear of the car was adapted to take a burner capable of holding 35KG (77LB) of charcoal which, when burned, produced a combustible gas.

The engine’s power dropped by a third to around 40HP, but on the plus side this was 40HP more than a regular 402 could produce if no gasoline was available.

The system was also offered in the DMA light truck, which had the same engine as the 402.

According to Peugeot, more than 2500 vehicles with charcoal generators were produced from 1940 to 1944.

-

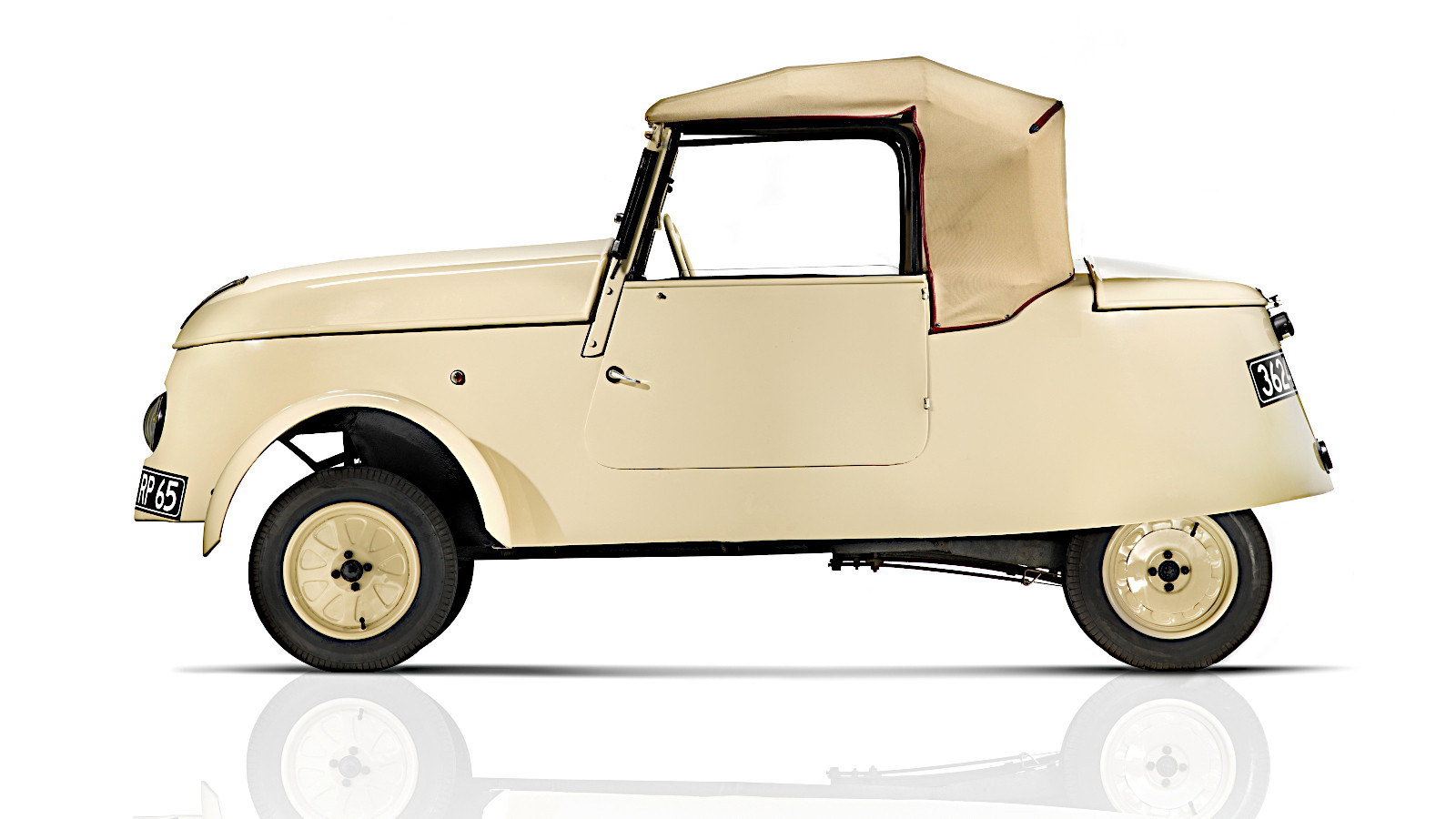

21. Peugeot VLV (1941)

The charcoal-fueled 402 wasn’t Peugeot’s only response to the wartime gasoline crisis in France.

In 1941, it began production of the VLV (Véhicule Léger de Ville, or Light Town Car), a tiny two-seat vehicle with a rear-mounted electric motor.

The VLV’s 20mph top speed was hardly impressive, but as one sympathetic reviewer put it, “With the Peugeot electric car, one can achieve the same performance as a first-class trained cyclist, and without the slightest tiredness.”

Peugeot built 377 VLVs before the Vichy regime ordered it to stop in 1943.

-

22. Mercedes-Benz 230 (1943)

From April 1943 to February 1944, Mercedes-Benz produced 34 special examples of the 230 (one of the very few cars it built during wartime) which are sometimes said to have been powered by coal.

This could be a mistranslation, because there are other references to a ‘wood-gasifier’ system, first used in the 170V in 1939.

As with the Peugeot 402, this appears to have involved creating gas to power the engine by burning charcoal, which is a very different thing from coal.

In the 170V, the system reduced the power output drastically. To mitigate this, at least to some extent, in the 230, Mercedes increased the capacity of its straight-six engine from the usual 2.3 liters to 2.6 liters.

-

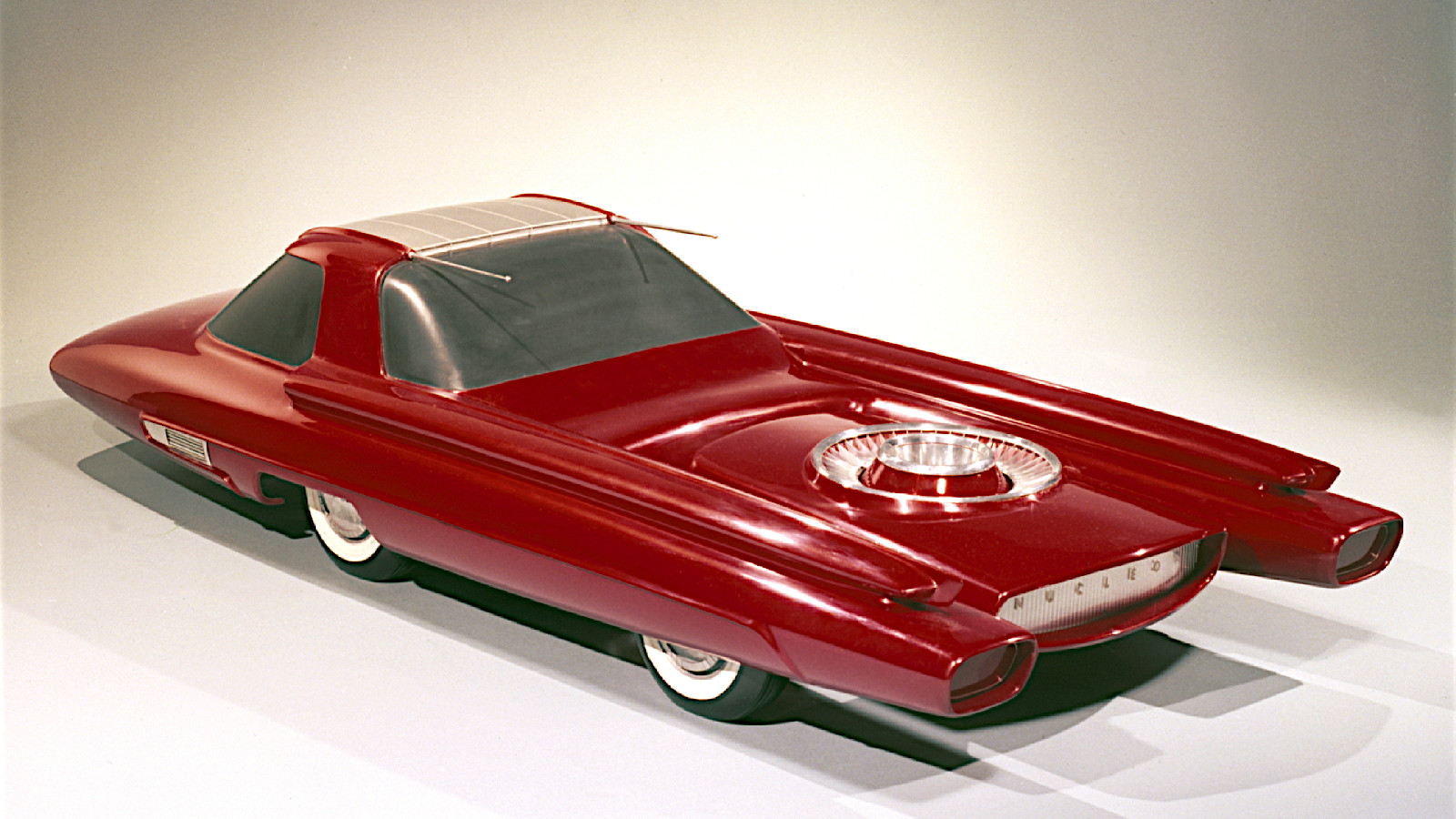

23. Ford Nucleon (1958)

The enormous range of a car powered by a nuclear reactor becomes less attractive when you factor in the potentially horrifying emissions, but that hasn’t stopped some manufacturers – among them Ford, Simca and Studebaker-Packard – from at least thinking about them.

The Nucleon, ‘designed on the assumption that the present bulkiness and weight of nuclear reactors and attendant shielding will some day be reduced’, was the first of two concept models, revealed in 1958 and showing, as an accompanying brochure pointed out, ‘the designer’s unwillingness to admit that a thing cannot be done simply because it has not been done’.

Fancy talk, indeed, but the fact is that, more than 60 years later, this particular thing has still not been done.

Ford has never built a functional nuclear car, and nor, to the best of our knowledge, has anyone else.

-

24. Henney Kilowatt (1959)

Although this electric car was branded as a Henney, the coachbuilder of that name was only one of several companies involved in its development.

The Kilowatt was produced in very small numbers in 1959 and 1960.

Possible reasons for its failure include the high cost of the electric system, the fact that almost nobody was interested in EVs at the time, and the further fact that it was based on the Renault Dauphine (representative model pictured) which, though previously very popular in the US, was by that time developing a terrible reputation for rust.

Fewer than half the 100 standard Dauphines provided by Renault were converted, and most of those were bought by electric-utility companies.

-

25. Chrysler Turbine (1963)

Fiat, General Motors, Renault and Rover all approached the idea of a car powered by a gas turbine (similar to a jet, but turning a shaft rather than simply blowing hot air out the back) with varying degrees of enthusiasm, but only Chrysler made one available to the public.

Around 50 were built, and not sold but loaned out in an evaluation program which ran between 1963 and 1966.

We’re including the Chrysler in a feature on alternative-fueled vehicles because it could run on just about anything combustible, including diesel, kerosene and – on one widely attested occasion when the President of Mexico took one out for a test drive – tequila.

Gasoline was fine, too, but preferably unleaded, because Chrysler found that the leaded stuff damaged the turbine.

-

26. Scamp (1966)

The Scamp was one of several tiny British electric cars which appeared briefly in the 1960s.

Perhaps unexpectedly, it was designed and built by Scottish Aviation, whose main expertise lay in creating aircraft.

The design brief – providing a vehicle suitable only for town or city commuting, which did not have to travel very far between battery charges – seemed reasonable enough, at least until the car was independently reviewed.

According to quoted but apparently unpublished sources, this went very badly, and the Scamp project was canned before anyone had a chance to buy one.

-

27. Mars II (1967)

The Mars II was the first car put into production by what was then known as the Electric Fuel Propulsion Corporation.

Following the single Mars I – based, like the Henney Kilowatt – on the Renault Dauphine, the Mars II was an electric conversion of the more modern Renault 10 (a standard example of which is shown above).

According to a paper published by SAE International in 1968, the car had regenerative braking, a top speed of 60mph, and a range of between 70 and, in ideal conditions, 230 miles, plus its battery could be recharged to 80% capacity in 46 mins.

Appealing as this was, the Mars II resembled the Henney Kilowatt in that fewer than 50 were built in two years.

-

28. Chevrolet Chevelle (1969)

The Chevelle SE 124 was an experimental car commissioned by General Motors and converted from a standard model by Bill Besler, who along with his brother George had bought the remains of the Doble company.

The engine was the back half of a Chevy V8, modified extensively to run on steam.

The energy to convert water into steam was provided not by coal, as might previously have been the case, but by kerosene, and once the steam had done its work it was condensed back into water so that the process could begin again.

GM paid Besler for his efforts, but decided not to proceed with either this project or another one which we’re going to look at next.

(Representative model pictured.)

-

29. Pontiac Grand Prix (1969)

Superfically similar in concept to the Besler-converted Chevelle, the experimental Grand Prix had a powertrain developed by GM itself.

With an output of around 160HP, it was more than three times stronger than Besler’s steam engine, which inevitably provided far greater performance.

According to a contemporary report, though, it was also 204KG (450LB) heavier than a Pontiac V8 gasoline engine, and was likely to cost three times more to build, even when the unit cost benefits of mass production were taken into account.

In the same report, GM expressed the opinion that ‘the steam car is a contender’, but that suggestion has proved to be optimistic.

(Representative model pictured.)

-

30. Lunar Roving Vehicle (1971)

While electricity remains, for now, a minority power source in Earth-bound vehicles, it is the only one that has ever been used for cars driven on the moon.

The Lunar Roving Vehicle, informally known as the Moon Buggy, was developed largely by the General Motors Defense Research Laboratories, though Boeing was responsible for the power system, navigation, communication and integration with the lunar-landing module.

With four electric motors providing a total output of 1HP, the LRV wasn’t exactly quick, though it is presumably the current holder of the Lunar Speed Record.

In case you’re wondering how a car could possibly fit in a spaceship, engineer Ferenc Pavlics had the idea of making it foldable, so that its volume was a very compact 30 cubic feet while it was being transported.

-

31. Enfield 8000 (1973)

Enfield introduced the tiny electric 8000 around the time of the first fuel crisis of the 1970s.

That handy coincidence was overshadowed by the fact that the car was mightily expensive, even though many of its parts were bought in from mainstream manufacturers, rather than being developed specially for the purpose.

A not universally agreed-upon number somewhere over 100 examples were built until production came to an end after three years.

With a power output of less than 10HP and a curbweight of nearly a metric tonne, the 8000’s performance was as modest as you might expect, though a street-legal drag version covered a standing quarter-mile in a very impressive 9.8 secs in 2016.

-

32. CitiCar (1974)

Unappealing as it may look to 21st-century eyes, the CitiCar was practically the Ford Model T of 1970s electric vehicles.

Sebring-Vanguard built more than 2000 examples at its factory in Florida before calling a halt in 1977.

The rights were then acquired by Commuter Vehicles, which updated the design slightly, changed the name to Comuta-Car and built about the same number of this version.

-

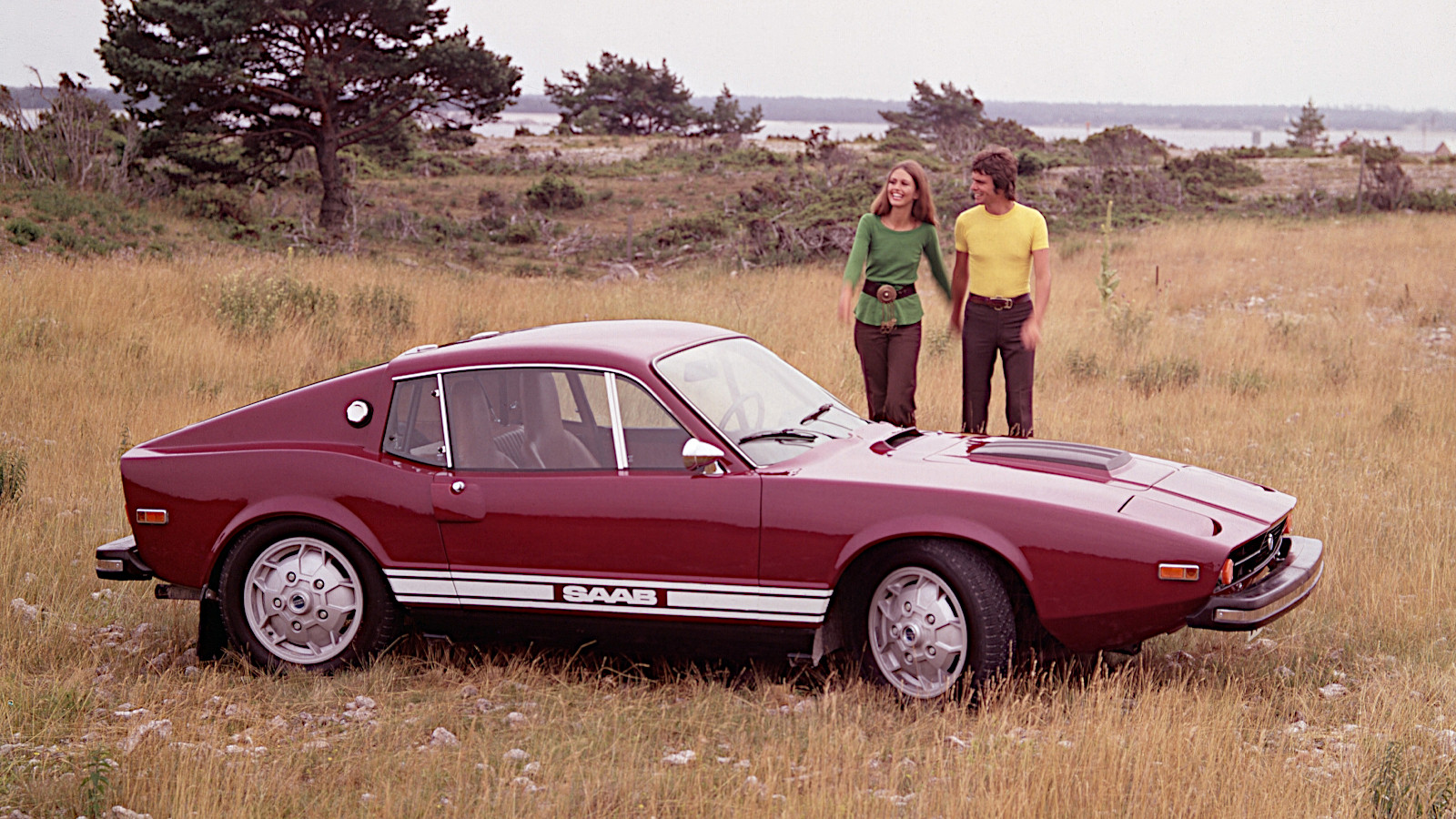

33. Saab (1974)

A magazine article published in December 1974 gave details of a steam engine which was being developed by Saab.

Just over a year later, in early 1976, SAE International published a paper written by Ove Platell, giving details of how the project was progressing.

The engine appears to have been fitted at some stage to a Saab Sonett III (representative model pictured), normally powered by a Ford V4, but as with the slightly earlier GM steamers the idea was dismissed before anything like it reached production.

-

34. Steam Cat (1974)

Peter Pellandine, a British designer who worked both in the UK and Australia, was an enthusiast both of small sports cars and of steam engines.

He combined the two for the first time with the Steam Cat, which was developed into the more conventional gasoline-engined Pelland Sports.

Pellandine also built a car intended to beat the 127.66mph achieved by the Stanley Rocket in 1906, but the Stanley’s record remained intact for a few years longer.

-

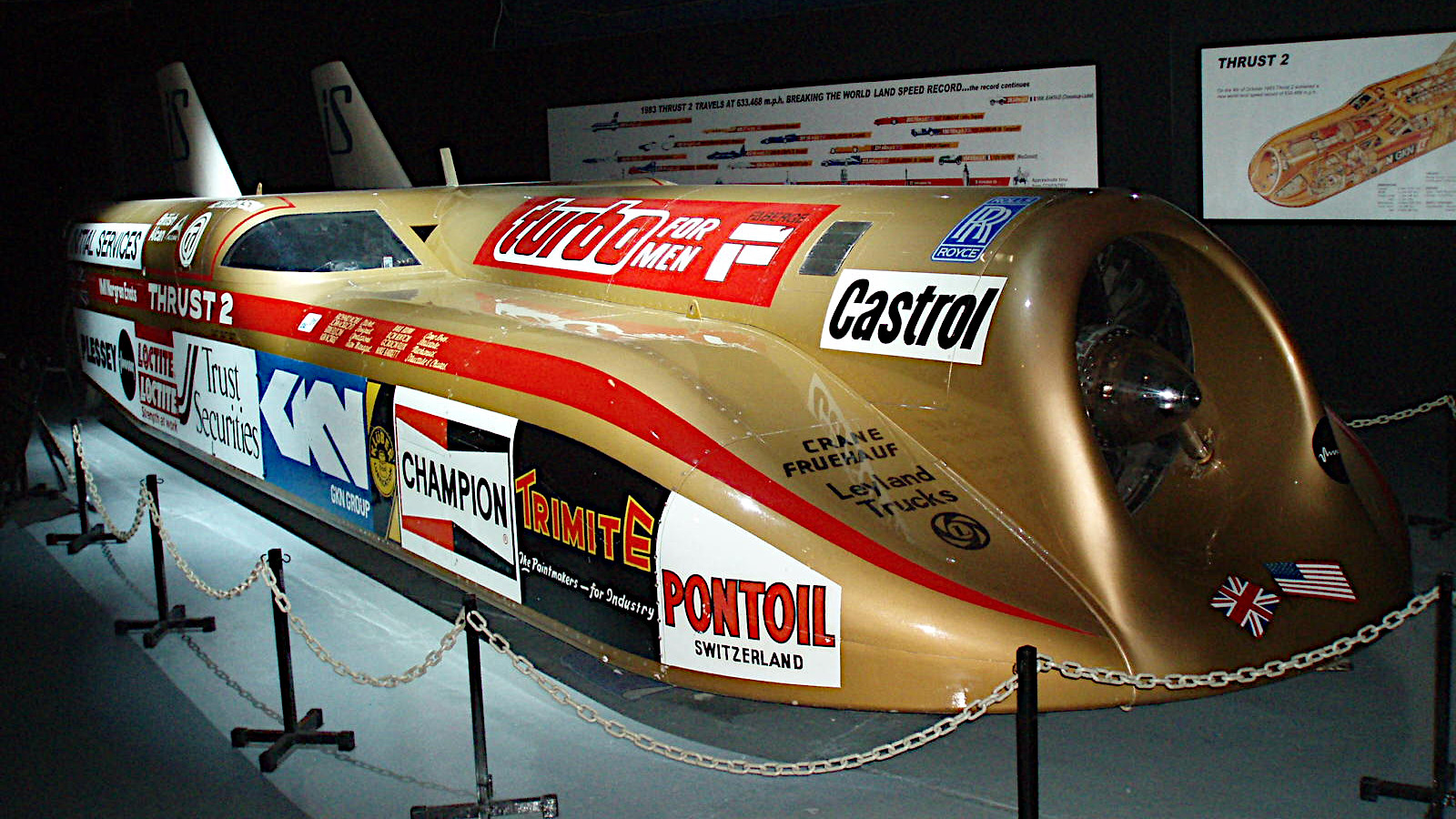

35. Thrust 2 (1983)

Jet engines have not been used in standard road cars, for obvious reasons, but they have been reasonably common for several decades in dragsters and Land Speed Record contenders.

In the latter category, jets were used exclusively during an incredible period when the record was raised from 407mph in August 1963 to 600mph in November 1965.

A new era seemed to have dawned when Gary Gabelich’s rocket-powered Blue Flame raised the record to 622mph in 1970 and held on to it for 13 years, but Richard Noble’s Thrust 2 brought jet cars back into play when it hit 633mph.

The LSR has been held by jets ever since. The current holder, Thrust SSC (the twin-engined follow-up to Thrust 2), is the only vehicle ever to have exceeded the speed of sound on land, having raised the mark to 763mph in October 1997 in the hands of Andy Green.

-

36. Solectria Force (1991)

The Force, built by Solectria Corporation of Wilmington, Massachusetts, was a Geo Metro (itself a Suzuki marketed by General Motors) with the standard engine and transmission replaced by an electric drivetrain.

Only a few hundred were produced, but the Force performed exceptionally well in the American Tour de Sol electric-vehicle rally, winning the Production class several times.

Solectria’s Sunrise model, based on a composite bodyshell, was even more spectacular, recording an unofficial 375 miles on a single charge in the 1996 Tour de Sol event.

Unlike the Force, however, the Sunrise never got past the prototype stage.

-

37. General Motors EV1 (1996)

The EV1 was GM’s first, and perhaps most controversial, attempt to put an electric car in the hands of the American motorist.

It was sold, rather than leased, from 1996 to 1999, at which point the program was abandoned.

GM said this was on the grounds of cost, but a contrary opinion that the company was trying to kill electric cars was strongly voiced.

Nearly three decades later, when the General has committed itself to designing and building EVs on a grand scale, this seems rather strange.

-

38. Honda EV Plus (1997)

The EV Plus was yet another late 1990s electric vehicle produced by a major auto maker, and the one most likely to appeal to people who enjoyed compact hatchbacks.

Around 300 were produced, and made available on lease only, from 1997 to 1999, after which Honda concentrated on its debut petrol-electric hybrid, the first-generation Insight.

The most dramatic EV Plus was a competition-prepared version in which Teruo Sugita set a new record for electric machines at the Pikes Peak Hillclimb in 1999.

Sugita’s time of 15 mins 19.91 secs has since been eclipsed by the 7 mins 57.148 secs achieved by Romain Dumas in the all-electric Volkswagen I.D. R in 2018, an improvement not entirely explained by the fact that the gravel parts of the course were resurfaced with Tarmac in 2011.

-

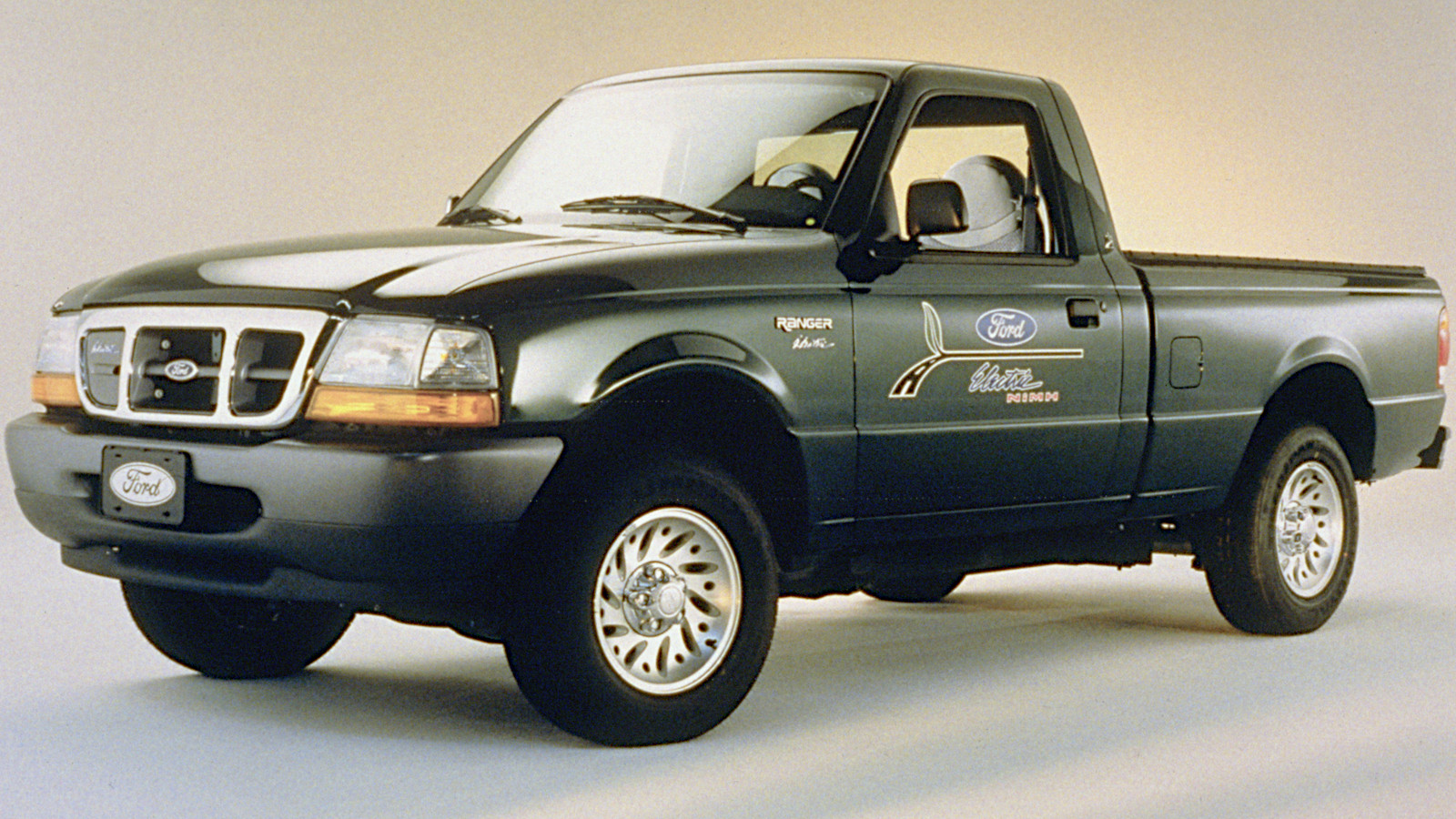

39. Ford Ranger EV (1998)

GM followed the EV1 with its first electric pick-up truck, the Chevrolet S-10 EV, but this was available for only two model years.

Ford persevered for longer with its equivalent vehicle, the Ranger EV, which (as the name suggests) was simply a Ranger pick-up with an electric drivetrain.

Available on either a lease or an outright-purchase basis (the latter being significantly more popular), the Ranger EV was available from the 1998 to 2002 model years, a period during which customers who preferred SUVs could lease the first-generation Toyota RAV4 EV if they chose to.

-

40. Imagination (2009)

Fred Marriot’s 127mph in the Stanley Rocket back in 1906 remained the highest speed recorded by a steam-powered vehicle for more than a century.

It was finally beaten by the British Steam Car project’s Imagination in August 2009.

Charles Burnett III set a new international mile record of 139.843mph on 25 August 2009, then handed the vehicle over to Don Wales (grandson of multiple record breaker Sir Malcolm Campbell), who raised it further to 148.166mph the following day.