-

© Artcurial

© Artcurial -

© Bose

© Bose -

© ClearMotion

© ClearMotion -

© fapu.de

© fapu.de -

© Daniel van Niekerk

© Daniel van Niekerk -

© Ford Heritage Vault

© Ford Heritage Vault -

© Ford Heritage Vault

© Ford Heritage Vault -

© Brightwells

© Brightwells -

© Thales Group

© Thales Group -

© I.DE.A Institute

© I.DE.A Institute -

© I.DE.A Institute

© I.DE.A Institute -

© Bill McChesney, CC-BY 2.0

© Bill McChesney, CC-BY 2.0 -

© Bonhams

© Bonhams -

© Honda

© Honda -

© Jon Burgess

© Jon Burgess -

© Brightwells

© Brightwells -

© SWVA

© SWVA -

© CCA

© CCA -

© Jon Burgess

© Jon Burgess -

© Toyota

© Toyota -

© Honda

© Honda

-

Clever thinking

Since the arrival of the motor car, inventors, entrepreneurs and academics have tried to improve it.

The decades were not kind to outsiders. For example, speaker and stereo manufacturer Bose, whose electromagnetic suspension has yet to see the light of day.

Or Austrian shoemaker Polyair that wanted to simplify the means of tyre production; vested interests saw that its LIM carcass didn’t take to the road. Lawmakers also had their say, restricting the march of prismatic side mirrors and rendering lean-burn engines obsolete.

Has the passage of time redeemed these inventions – and many more? Let’s find out.

-

1. Bose electromagnetic suspension

In the automotive industry, audio firm Bose was a rank outsider. But its founder, Dr Amar Bose, was a petrolhead, having owned an air-sprung Pontiac and hydropneumatic Citroën, and he wanted a sophisticated middle ground between the two.

Bose realised that the way a speaker driver reacted to sound could be transposed on to the suspension of a car. Despite the costs involved, a skunk works within the firm was formed in 1980, named ‘Project Sound’, to investigate.

Two decades of development produced an ‘active’ suspension, comprised of computer-controlled electromagnetic linear motors. Reacting thousands of times a second, test vehicles so equipped were kept level and cushioned, regardless of the road surface. As per the system’s ‘active’ title, it reacted to road imperfections before occupants could perceive them.

-

Bose electromagnetic suspension (cont.)

Demonstrated to the press in 2004, the results – seen on a 1994 Lexus LS400 – were dramatic. The standard car heeled over and wallowed in bends; the Bose-modified Lexus remained unperturbed across broken surfaces, and during violent lane changes.

Unfortunately, cost, weight and complexity were against the project, despite its undoubted competence. Citroën’s Xantia Activa – which made production (and UK sale) in 1996, achieved similar results to Bose’s system, using a 10-sphere, interconnected evolution of its Hydractive II hardware, known as ‘SC.CAR’.

The rights to Bose’s electromagnetic suspension were finally sold to another firm, ClearMotion, in 2017; since then, work has continued apace, but no maker has adopted it for use yet. Bose itself spun the active technology off into truck seats; the haulage industry baulked at the costs involved.

-

2. Polyurethane (plastic) tyres

In 1975, Austrian plastics manufacturer Polyair made a breakthrough which should have simplified pneumatic-tyre production for cars. It devised a way of injection moulding (‘die casting’) cordless tyres using polyurethane, building on previous research by Firestone and Goodyear.

Called ‘LIM’, it was more resilient to punctures than a rubber-moulded tyre, could be made in any colour, and built up less heat when run up to speed.

By 1983, intensive testing had, Polyair claimed, produced a polyurethane tyre that was the equal of contemporary rubber.

Polyair maintained that production was far simpler than existing tyres. The equipment needed to produce LIMs was far less complicated and could be carried out in industrial estates or on-site in car factories, rather than having to buy tyres in by their thousands.

-

Polyurethane (plastic) tyres (cont.)

Contemporary reports spoke of successful governmental trials in Venezuela against locally produced radials, and extensive Arab investment.

Alas, stung by reports of poor handling characteristics from its first-generation, handmade tyres in 1975, Polyair struggled to find friends in the established tyre industry.

Three years later, however, BF Goodrich acquired a minority stake in the firm. Published Polyair patents, many since expired, date back to 1977, 1978, 1980 and 1985.

Instead, the lessons learned went back into the production of polyurethane tyres for the materials-handing and retail industries – where millions of castor-mounted tyres are fitted to roll-cages (supermarket trolleys) and fork-lifts every year.

-

3. Wind-down rear windscreens

Good ventilation for passengers is important for any car interior designer, be their cars large or small.

With the widespread adoption and affordability of air-conditioning still some way off in the early ’50s, Ford proposed a mechanical alternative: a rear windscreen that could be retracted up and down as if it were in a door aperture.

It first appeared in the 1955 D-528/Beldone concept car, but it wouldn’t be on sale for another two years until it had a name: Breezeway.

-

Wind-down rear windscreens (cont.)

In truth, Breezeway, fitted to the unpopular Mercury Turnpike Cruiser, was an adaptation of the hinged rear windows found on many rumble-seat coupes.

But Ford, keen for whatever marketing edge it could assert over Chrysler and General Motors, offered the (again untitled) feature on its 1958-’60 Continental, and revived the Breezeway nameplate for a second time between 1963 and 1968 on various Mercury models, including the Monterey seen here.

At dealers, Breezeway wasn’t a hugely popular option. While it kept back-seat passengers cool, smells, road debris and other unpleasant things easily found their way into the cabin.

Smaller, more efficient air-conditioning units, produced on a vast scale, saw to the demise of Breezeway; coveted by collectors, it’s remembered now as an interim curio.

-

4. Cast-aluminium frame construction

Aluminium-bodied cars have found favour in the past 30 years: improvements in material technology have allowed the likes of Aston Martin, Audi, Honda, Lotus and Jaguar to reap the rewards it offers in terms of corrosion resistance, weight saving and recyclability.

Engineer, salesman and front-wheel-drive trailblazer, Jean-Albert Grégoire, had no such sophistication available to him in the ’50s, when he sought a means of getting his cast-aluminium frame (carcasse en aluminium coulé) method of construction, pioneered on the pre-war Amilcar Compound, into showrooms.

Steel was a valuable commodity in post-war France and many pre-war luxury car makers, including Hotchkiss, had a moribund range of cars that didn’t fit into the Pons Plan of industrial reconstruction.

Aluminium had few restrictions and was being promoted aggressively by the Aluminium Français (AF) consortium – and Grégoire’s earlier design for a small car produced with AF, the Aluminium Français Grégoire (AFG), failed to reach production, deals with British and Australian governments having fallen through.

-

Cast-aluminium frame construction (cont.)

Closer to home, Rover had used traditionally made aluminium panels for its 75 (P4), launched in 1948, owing to similar material restrictions.

Hotchkiss bought the rights to Grégoire’s design. The new car, named the Hotchkiss-Grégoire in his honour, updated the firm’s range at a stroke.

The ‘H-G’ offered a flat-four engine, all-round independent suspension, rack-and-pinion steering, and front-wheel drive. The running gear and panels were attached to a one-piece, cast-aluminium ‘frame’ comprising a scuttle-bulkhead, front windscreen pillars and outer sills.

Brilliant in theory, it was expensive and time consuming to produce: Hotchkiss went broke producing the H-G, which cost more than double that of the (hardly unsophisticated) Citroën Traction 15CV.

To add insult to injury, buyers didn’t like the H-G’s bulbous styling, either; its shape was determined by aerodynamics professor Marcel Sédille to be as slippery as possible.

With sales of its conventional Anjou saloon faltering, Hotchkiss’ commercial and military vehicle contracts kept it afloat until mergers eventually integrated it into today’s Thales Group.

-

5. Prismatic side mirrors

In the early ’90s, thousands of words were written about de Montfort prismatic side mirrors – named after the Leicestershire university which helped develop them (a stick on ‘blind spot’ prismatic mirror was developed later, and remains unrelated to the de Montfort mirror).

A fully mechanical system (without the camera trickery used by modern equivalents), the units had a far flatter cross-section when attached to doors, reducing drag; per side, a viewing window was brought inside the car, lowering fatigue while eliminating blind spots.

-

Prismatic side mirrors (cont.)

Soon, the units were appearing on contemporary concept cars, embraced most enthusiastically by Italy’s I.DE.A Institute.

The de Montfort units appeared on its 1992 Grigua supermini and 1996 Vuscia/Jiexun people carrier.

The same year, Canadian-German OEM parts manufacturer Magna concluded a licensing deal with de Montfort to use its technology; since then, legislators, particularly in the United States, have been slow to recognise advancements in side- and rear-view mirror development.

-

6. In-car record players

Music on the move was a fanciful notion in the ’50s – at least in the United States drivers could listen to the radio.

By 1956, however, Chrysler had an alternative: a specially engineered record player with an anti-skate mechanism to keep discs from skipping.

Inventor, CBS Laboratories, struck a deal with Chrysler to supply Imperial, Chrysler, De Soto, Dodge and Plymouth models with the ‘Highway Hi-Fi’ unit, which played specially sized, 45-minute-long records from CBS Columbia’s back catalogue.

Warranty claims and failures in service were common; having shelled out the extra for the player, buyers soon found that records that couldn’t be taken in the house and played were too much of an inconvenience (there were also no rock ‘n’ roll releases to choose from).

-

In-car record players (cont.)

By the time Highway Hi-Fi died in 1959, however, a new RCA Victor unit, the AP-1, was ready to go by 1960. This box played RCA-compatible 45rpm vinyl – and self-ejected them when done.

Philips, heavily inspired by the AP-1, released the Auto Mignon (pictured) a year later to a jubilant European audience. Sir Paul McCartney had an example of the latter in his Aston Martin DB4, but we doubt he’d have been happy with the heavy stylus pressure exerted on his records, a crucial component in the Auto Mignon’s anti-skip mechanism to keep the needle in the groove.

The four-track, eight-track and microcassette (another Philips invention) did to the in-car record player what air-con did to the Lincoln-Mercury Breezeway.

-

7. In-car motorcycles

Cars cause congestion, but motorcycles can still get through. That’s the essence of Honda’s 1981 Motorcompo, a fold-up, 49cc motorbike ‘accessory’ that fits in the boot of its City supermini (the UK’s first, short-lived Jazz), launched simultaneously.

Priced at the equivalent of £700 (or thereabouts), the Motorcompo was promoted in period by ska band Madness and appeared frequently in Kōsuke Fujishima’s You’re Under Arrest manga (and later anime).

Honda was so sure of its park-and-ride-without-the-buses-scheme that it forecast 10,000 Motocompo sales a month; in reality, around 53,000 were delivered within a two-year period.

While far from a novel concept, at least as far as its portability was concerned (in latter years, Honda’s heritage division displayed the City-Motocompo duo with a period Denta generator as another icon of mobility), no one else has attempted to sell a car with a back-up ’bike you could ratchet-strap into the boot.

-

In-car motorcycles (cont.)

Zagato’s 1992 Z-Eco came the closest, a customised Fiat Cinquencento with its cabin converted and halved into a tandem canopy, with an electric bike mounted lengthwise down the car’s sectioned body.

Few used the Motorcompo for its intended purpose. While it was road legal, it had a top speed of only around 30mph. Like the Sinclair C5, its operators were low and vulnerable to bumps, deep puddles and large vehicles.

Its sheer audacity made it a cult hit among ’80s revivalists, who realised it would fit in the load bays of surviving high-performance, wide-arched City Turbo IIs for maximum niche appeal. Values skyrocketed; Motorcompos now sell for more than roadworthy Citys, unless a Turbo II is in the picture.

Honda is very much aware of what the Motocompo became: in 2011, it showed off an electric foldable scooter, known as the ‘Motorcompo’, and, nine years later, it trademarked the name ‘Motorcompacto’ for future use.

-

8. Hayes Selfselector CVT

Continuously variable transmissions are nothing new – in fact, well before the van Doorne (DAF) ‘rubber band’ units, US engineer Frank Anderson Hayes filed a 1929 patent for a toroidal unit.

He soon signed an agreement with Austin and Cloudsley Engineering in the UK to develop his ‘Variable Speed Power Transmission’ further; with exclusive rights, Austin advertised the gearbox as ‘a simplification, not a complication of the transmission’, adding that ‘it dispenses with all gears (except to give reverse) and all clutch operations (except when starting and stopping). There is no noise; the drive is practically silent.’

Further marketed under the strapline ‘driving simplified – gear changing abolished’, buyers could specify the Hayes Selfselector on the otherwise outwardly identical York or Westminster-bodied Austin 16 and 18, from 1933, with an improved (simpler) Mk2 appearing in 1935.

It was an expensive option, regardless, adding £40 (nearly £3200, inflation corrected for 2022) to the price of the car, and a clutch still needed to be engaged and disengaged when moving off and coming to a halt.

-

Hayes Selfselector CVT (cont.)

The high price to drive behind a Hayes put many buyers off in period – and faults were common, given the tight tolerances and special ‘Drivex’ fluid needed in service. The Hayes box was pensioned off before WW2.

When working, however, Hayes-equipped cars used less fuel than their manual brethren.

Despite persistent rumours that General Motors tried to buy the licence, Perbury Engineering developed the CVT further for car use, followed by Leyland Truck and Bus, whose Advanced Technology division fitted a unit using Hayes principles to an experimental National bus chassis in the search of better fuel economy.

Completed in 1984, funding for production disappeared with the firm’s merger into Volvo Bus in 1987-’88, so it remained a one-off.

-

9. Miller Cycle Engines

Suck, squeeze, bang – blow. The four-stroke ‘Otto’ cycle has been the basis of internal combustion for more than 100 years, but in 1957, Ralph Miller modified it to produce more economy.

Holding the inlet valve open longer makes for a more efficient compression stroke, provided the excess air expelled can be scavenged (in effect, replaced) by a supercharger.

That’s exactly what Mazda used with its Xedos 9 Miller Cycle, released in the UK in late 1998. Despite its weight, automatic gearbox and 210bhp, 2.3-litre V6 engine, fuel economy was impressive for the time, with more than 30mpg quoted at the pumps. Executive cars weren’t known at the time for their parsimony; given the dipsomaniac thirst of its contemporary rotary cars, the Xedos 9 Miller Cycle was a welcome addition to Mazda’s range.

-

Miller Cycle Engines (cont.)

Slow sales meant that the model lived for fewer than two years in the UK, though it was sold into the 2000s as the Millennia and Xedos 800 elsewhere in the world.

Judged by UK standards, the Xedos 9 Miller Cycle could be seen as a dead-end, but that doesn’t tell the full story.

While Mazda never used Miller principles on a V6 again, it did use them in later four-pots in in its direct-injection ‘SkyActiv’ engine range, first as a Japanese market only, 1.3-litre engine for its Demio (Mazda 2) small car in 2007, and later as the SkyActiv-G for worldwide use from 2012. Three years later, Volkswagen Group also applied Miller principles to its four-cylinder TFSI engine range, attracted by the same fuel savings.

Like its so-called ‘fifth stroke’, the Miller Cycle engine hasn’t outstayed its welcome.

-

10. Lean-burn engines

Catalytic-converter requirements – and increasingly tightening emissions legislation for NOx – saw off lean-burn engines by 2006, but for several decades, they were seen as a way of improving fuel economy.

Chrysler, Ford, Honda, Mitsubishi, Honda and Toyota all had various goes at the lean-burn engine, with varying results (and fuel savings).

The ideal air-to-fuel ratio is 14.7:1. Adding more air leans out the mixture, resulting in a weaker or ‘leaner’ burn at low speeds or on part-throttle loads, improving fuel economy.

Having a localised ideal mixture near the spark plug, and a weaker mixture elsewhere in the pot that can be ‘lit’ afterwards, is one way of achieving this goal.

-

Lean-burn engines (cont.)

Ford worked on the ‘swirl’ and combustion-chamber shape that helps with ‘lean burn’ in its Canted Valve Hemispherical (CVH) engine, both in ‘true’ US and European guises.

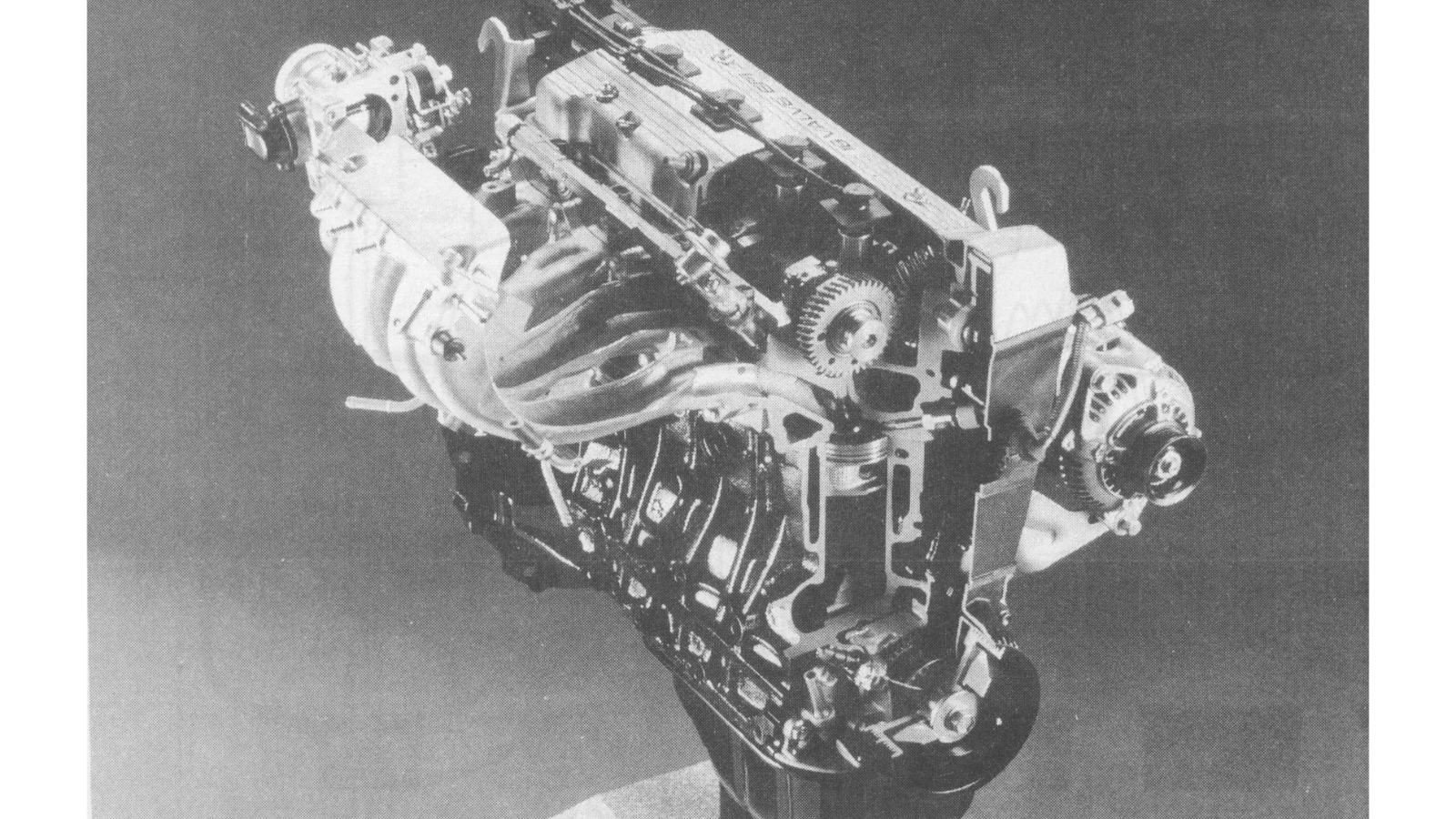

Honda, having advanced stratified charge engine technology with its Compound Vortex Controlled Combustion (CVCC) engine, abandoned it for its computer-controlled fuel injection (PGM-FI) programme. The CVCC unit was produced to meet emissions standards without the need for a catalytic convertor: its engineers argued that cat-equipped engines used more fuel and produced more C02 as a result./p>

As legislative emphasis shifted increasingly towards NOx emissions reduction, Honda went on to develop subsequent lean-burn engines with wide-band sensor-managed fuel injection systems; one such unit, the 1.0-litre, ECA ‘triple’, helped the first-generation Honda Insight hybrid of 1999 to achieve hitherto unheard-of fuel economy figures.

Toyota’s British-built Carina E offered a lean-burn engine to European motorists from 1993; its 1.6-litre 4A-FE was driven out of the EEC by changing exhaust laws, but lived on in other markets (and in 1.8-litre 7A-FE form) until 2002.

Mitsubishi toyed with lean-burn engines and direct injection in its Gasoline Direct Injection (GDI) units; fitted to various Carismas, Galants and Volvo S/V40s produced through the Nedcar scheme, the special catalysts the engines used were sensitive to high-sulphur fuels, as well as 10 per cent ethanol petrol (E10), introduced in 2021.