Although the body must have had paint in its 73 years, the trim is original.

The preservation of the nylon-cord fabric on the plump seats is aided by the sort of plastic covers that northern grannies in the ’70s used to protect their front-room sofas when saving for ‘best’, as if awaiting an impromptu visit from the Queen.

The leather is black (green or tan were also available) in a cabin that doesn’t quite equate to the outward size of the car in its lounging space, but is generally roomy by any other measure.

The two-door, pillarless hardtop Newport T&C was part of a restyle to celebrate Chrysler’s 25th anniversary

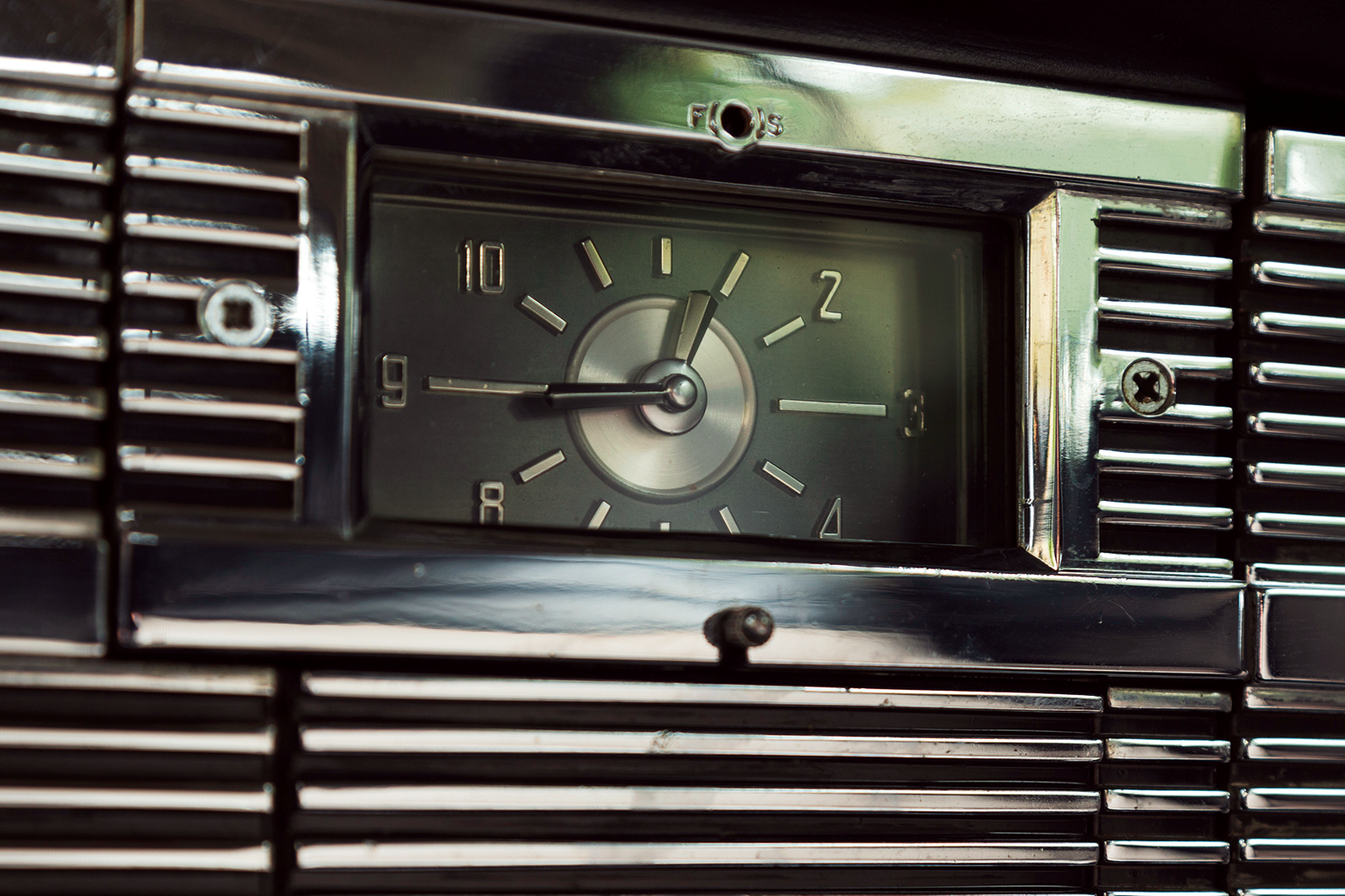

The glory of the Town and Country, beyond its woodwork, is its dashboard, a foot-deep swathe of straked and glittering chrome created in the school of design that gave us the Union Pacific Streamliners.

With its radio set styled in, and a variety of intriguing-looking switches for heating, lights and wipers, the focal point is a chrome half-circle the diameter of a football, with a cluster of minor gauges circling a boldly marked 110mph speedometer.

The cop-style spotlight on the driver’s door seems to have been a T&C standard feature.

Vague unassisted steering means this classic Chrysler is not a sporty drive

Likewise the chrome tray on an extending arm under the dash: the Americans were already trying to perfect the art of eating on the move.

Said dash is padded for comfort and safety, but the massive and unyielding steering wheel – on its equally unyielding column – offers nothing but certain death should you make high-speed frontal connection with a solid object.

In fairness, that seems unlikely because the Town and Country gives you few reasons to drive it anything but very carefully.

The dashboard design incorporates the all-important radio

Some big cars shrink around you, but this one never feels anything less than very large, very soft and very left-hand drive.

The whispering straight-eight oozes it down the road like melted cheddar from a fondue set, its modest power incidental to its silken torque and near silence.

Once into ‘high’, gearshifting is purely optional – or would have been, had it dawned on me that, like all 1950 T&Cs, this one has the semi-automatic Fluid Drive, whereby the high gears come in with the overdrive when you ease up on the throttle.

Stylish straked chrome dominates the Newport T&C’s dashboard

I drove it as a manual in first and direct third via the hefty right-handed column shifter, the point here being that you could throttle down to almost nothing in that gear and pull away without stalling or needing to control the clutch, and thus treat the car as a (very) lazy single-gear automatic.

This gives you time to negotiate the steering, which is not powered but a very light system with nearly five vague turns from lock to lock.

It feels like more, especially in tight, low-speed corners where your arms flail as you struggle to make enough turns in the time allotted.

Detailed handles continue the Chrysler interior’s plush appearance

Drawing a veil over the handling (or lack thereof), the big Chrysler’s brakes at least work fairly well, even if you’d never guess they were four-wheel discs.

That’s right: discs, although not the floating-caliper type but a split disc with twin wheel cylinders that expand to rub against the insides of a spinning casing that from the outside looks like a conventional finned drum.

Standard on the Imperial but a $400 option on the T&C, the system was available on the bigger Chryslers until ’55, when better servos evolved to revive the fortunes of the faithful drum.

1950 was the last year of the Chrysler straight-eight engine

Being neither patrician pre-war pioneer, tailfinned ’50s jukebox nor muscle car, this Town and Country’s place in the world of American cars is not easy to pigeonhole.

Even woodie fanciers may give it a wide birth simply because it is a coupe, not a wagon, although the earlier convertibles have made good at auction.

The likes of Ike Turner, Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley were not dreaming of these Chryslers when they penned their ‘boy gets car gets girl’ 1950s fantasies.

‘The huge rear bumper is deep enough for a presidential secret-service agent to comfortably perch on in a motorcade’

This was not a car to strive for, but what you bought when you’d already made it, got the girl, and had little left to prove.

The vibe of this car is not early rocker with too many hormones, but middle-aged crooner playing golf – and probably more Bing Crosby than Frank Sinatra.

In a world looking towards the jet age, the Town and Country already seemed to be hankering for simpler times.

Images: Luc Lacey

Thanks to: Gateway Auctions

Factfile

Chrysler Newport Town and Country

- Sold/number built 1949-’50/698

- Construction steel ladder chassis, steel and timber body

- Engine all-iron, inlet-over-exhaust 5302cc straight-eight, single carburettor

- Max power 135bhp @ 3400rpm

- Max torque 270Ib ft @ 1600rpm

- Transmission three-speed Fluid Drive semi-automatic, RWD

- Suspension: front double wishbones, coil springs rear live axle, leaf springs; telescopic dampers f/r

- Steering worm and roller

- Brakes Ausco-Lambert expanding discs

- Length 18ft 5in (5613mm)

- Width 6ft 3in (1905mm)

- Height 5ft 4in (1626mm)

- Wheelbase 10ft 9in (3277mm)

- Weight 3792Ib (1720kg)

- 0-60mph 23 secs

- Top speed 85mph

- Mpg 12-15

- Price new $4000

- Price now £40,000*

*Price correct at date of original publication

Enjoy more of the world’s best classic car content every month when you subscribe to C&SC – get our latest deals here

READ MORE

30 discontinued Chryslers

United estates: Buick Estate Wagon, Chrysler Town & Country and Ford Country Squire

Chrysler Airflow vs Volvo Carioca: Streamlined sensations

The tale of the wonderful classic British woodie

Martin Buckley

Senior Contributor, Classic & Sports Car