Acclaimed Lotus specialist Paul Matty then took on the project, but when Paul started to wind down his business, former employee Tim Garrington offered to complete the job.

As a hillclimber of 15 years standing, David intends to continue the Emeryson’s long history in the sport, which began with its first owner.

Fielding – who went on to design the Doune Hill Climb course in Scotland – took delivery of the car, first registered HSO 77, in March 1961 and along with his wife, Doreen, competed throughout that season.

‘We’re happily jostling with assorted Porsche Taycans and BMW M3s without breaking a sweat’

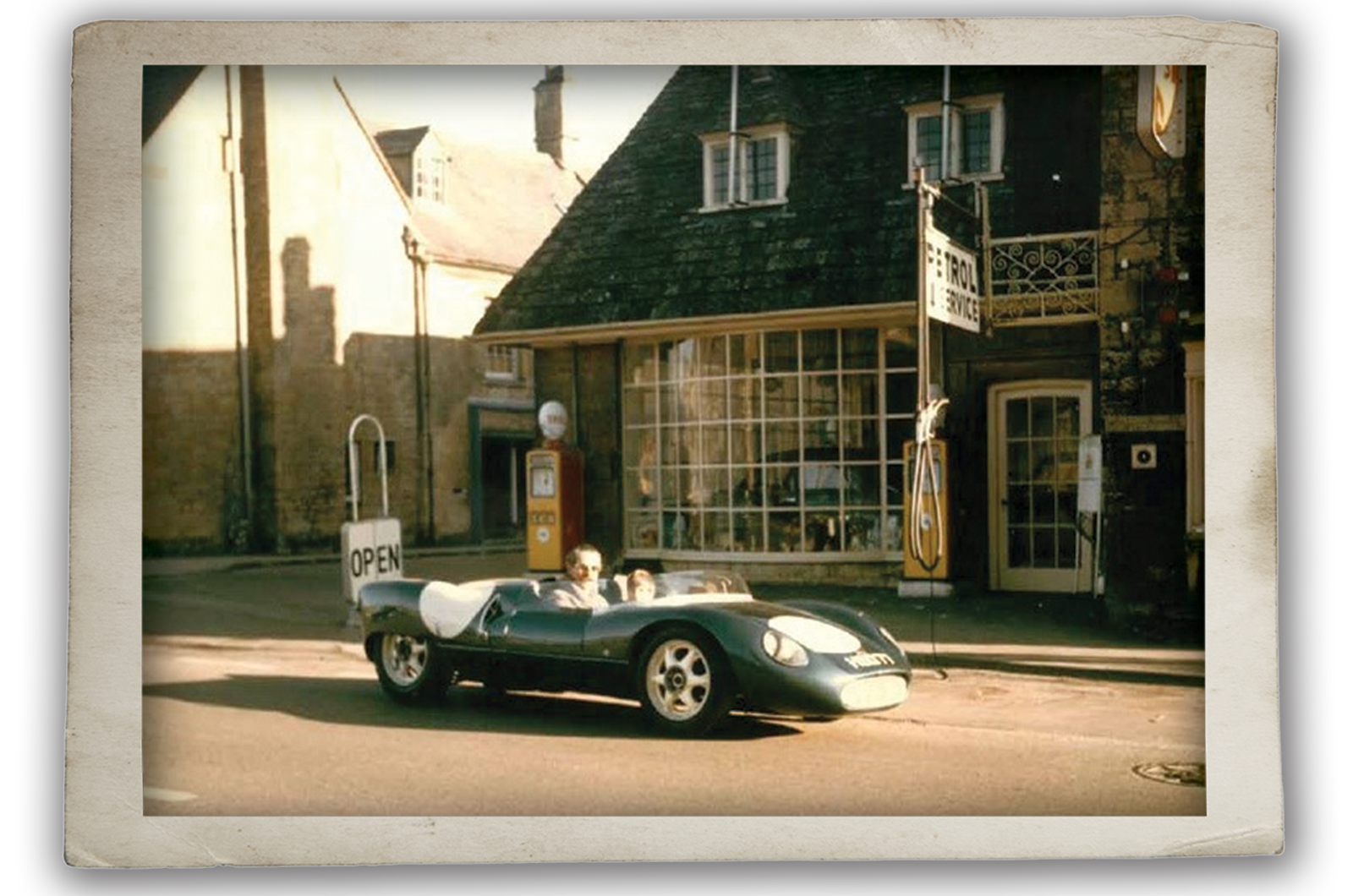

The Emeryson was then sold to Gerry Tyack of Curfew Garages in Moreton-in-Marsh in the November of the same year, before heading north to Graeme Austin of Wirral Racing in Birkenhead a year later.

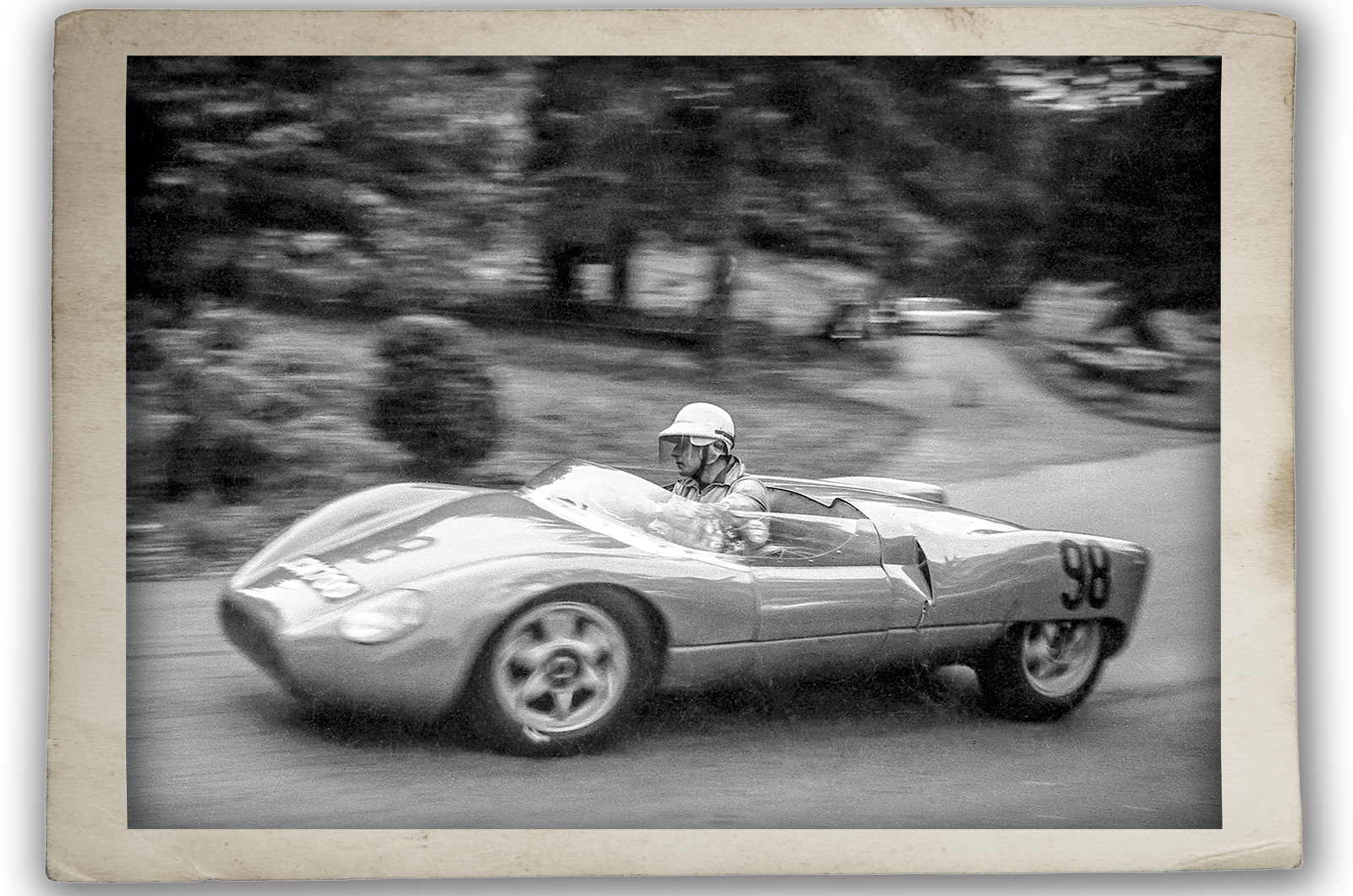

There’s photographic evidence of Austin competing in it at Chateau Impney soon after, on its new registration JCM 700, before he sold it to Jim McCartney, who kept the car from 1964 to ’66.

Well-known ’60s hillclimber Georgina Baillie-Hill then became JCM’s fifth owner and racer, after which the car was sold in 1971 to Richard Falconer, who kept it for 46 years.

The one-off Emeryson is a true road-legal racer

During that time the Emeryson was campaigned extensively, including notable entries with Emery driving at a support race for Thruxton’s 1976 European 5000 Championship and the following year covering 85 laps in the Silverstone 6 Hour Relay Race.

And perhaps it was this pit garage – or one nearby – in which JCM 700 was based for that 1977 event.

Alas, we don’t have access to the track today, but to be honest I’m more intrigued by how a historic competition car behaves on the road.

Swing open the token door, drop down into the tight clutches of the fixed, ribbed-leather driver’s seat and, really, you couldn’t sit much lower in the car.

The Emeryson has covered headlamps

But it’s comfortable and ergonomically pretty decent for a 60-plus-year-old racer.

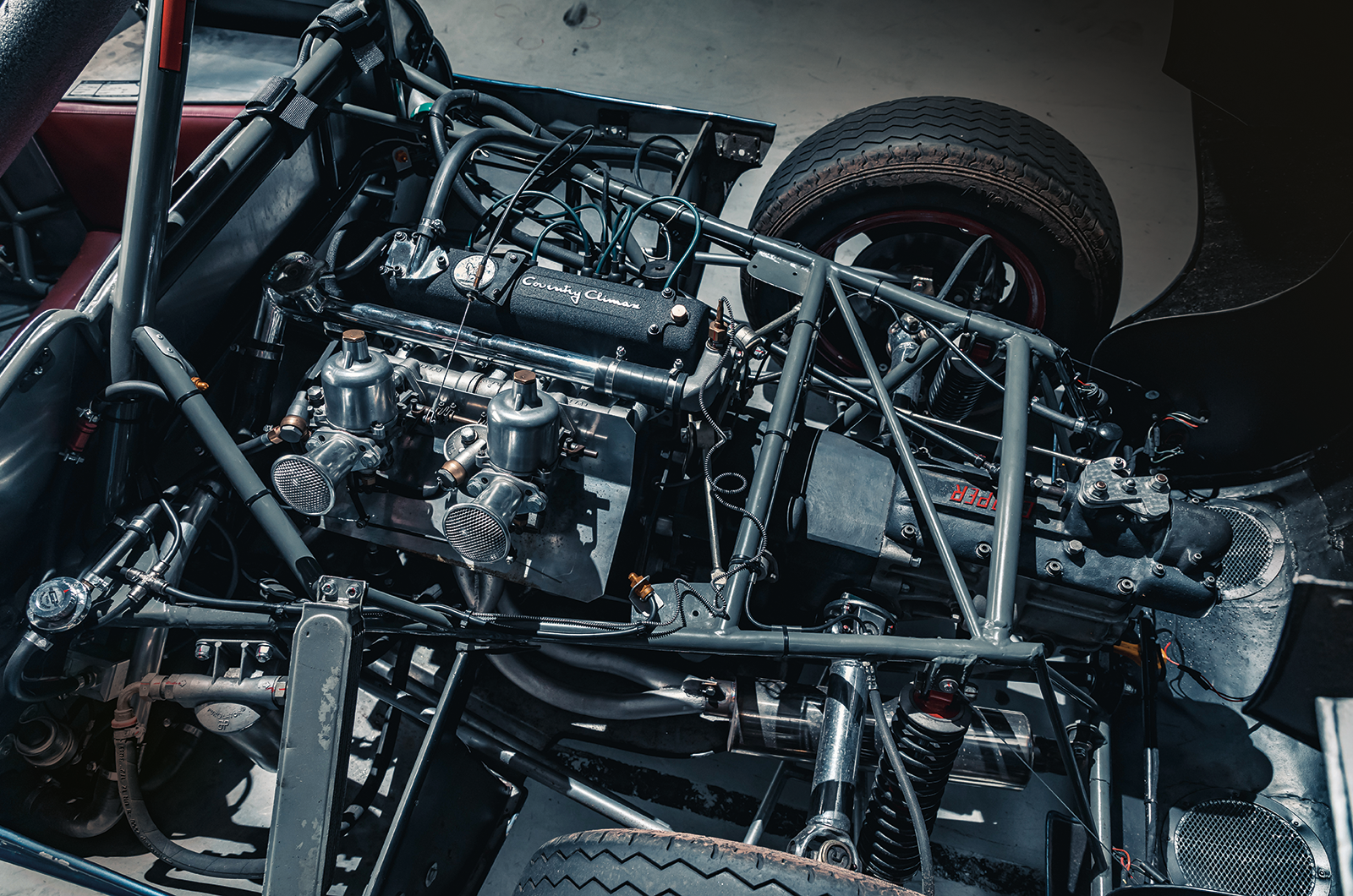

Elements of spaceframe surround you in the cabin as you face the three-spoke steering wheel with four dials behind it – two mains, for speed (to 120mph) and revs (redlined at 6500rpm), and two secondaries for oil pressure and water temperature.

Switchgear on the flat, crackle-black dash extends only to a couple of light switches, a choke lever and a battery cut-off.

Sparco harness clipped on, you search for the pedals by feel – the deep dash blocks your view of them – but they’re perfectly spaced, making heel-and-toeing a cinch.

The Emeryson’s brutal engine note is a reminder of its racing-car origins

Flick on the fuel pump, turn the ignition key and… My God, it’s loud!

By no means a cultured sound, but it makes you feel conspicuous, even at idle.

The clutch and throttle are light in action, and as you pull away the whine from the straight-cut gears accompanies the Coventry Climax’s steady crescendo.

Gear selection from the Citroën-based ’box is via a dash-mounted lever to the right of the steering wheel, with the gate cut deeply into the dashboard’s surface.

The Emeryson with its first owner in 1962

So this is what it feels like to drive a Formula Two car on the road.

Yes, the raucous engine note tempers your enthusiasm to clip the tacho’s redline after a while (which, thanks to the closely stacked ratios and short gearing, is easy to do), and the top of the low Perspex ’screen sits right in my sight line.

But few road cars provide such an immersive experience.

Strangely, it’s much like driving a first-series Lotus Elise, with about another 50% added to everything you feel and hear.

The Emeryson at Chateau Impney with Graeme Austin in 1963

The steering wheel jiggles in your hands, constantly alive with feedback.

Turn into a bend and there’s some understeer but almost no body roll; the rack’s ratio is also calm enough to prevent any nervousness at higher speeds.

The ride is supple, save some secondary brittleness, which allows for decent velocities to be carried on the uneven B-roads near to Silverstone.

And the unservoed discs have plenty of feel and strength, as long as you’re prepared to work them hard.

‘The only significant modification was angling the chassis’ vertical members outwards to fit two seats’

It’s only when we reach the A43 and ping up to 70mph in convoy with the moderns that there’s a hint of understeer where you’d least expect it, on the long sweepers; David suspects the issue is down to an over-zealous limited-slip differential, and easily fixable.

But the A43 is not where the Emeryson belongs.

Wearing road-legal numberplates was the loophole that granted a thinly disguised circuit racer licence to compete in hillclimbs, but on today’s evidence it also created a rather magical roadgoing sports car that never received the credit it fully deserved.

Images: Max Edleston

Thanks to: Paul Matty; Silverstone

Factfile

Emeryson

- Sold/number built 1961/ 1

- Construction steel spaceframe chassis, aluminium body

- Engine all-alloy, sohc 1460cc ‘four’, twin SU carburettors

- Max power 98bhp @ 6300rpm

- Max torque 91lb ft @ 4650rpm

- Transmission four-speed manual with straight-cut gears, limited-slip differential, RWD

- Suspension independent, at front by double wishbones rear lower wishbones, driveshafts as upper links; telescopic dampers, coil springs f/r

- Steering rack and pinion

- Brakes discs

- Length 11ft 6in (3520mm)

- Width 4ft 7in (1400mm)

- Height 2ft 8in (820mm, to top of ’screen)

- Wheelbase 7ft 2in (2200mm)

- Weight 1144lb (519kg)

- Mpg n/a

- 0-60mph 6 secs (est)

- Top speed 117mph

- Price new n/a

- Price now £100,000*

*Price correct at date of original publication

Enjoy more of the world’s best classic car content every month when you subscribe to C&SC – get our latest deals here

READ MORE

Siata 208 CS coupé: Ernie’s soul survivor

Lotus legend Paul Matty: a lifetime of service

How Renault turbocharged F1

The all-American hero: driving Lance Reventlow’s Scarab sports-racer

Simon Hucknall

Simon Hucknall is a senior contributor to Classic & Sports Car