Unlike the Le Mans Replica, the Mille Miglia featured a low, streamlined aluminium body but on the same A-shaped tubular chassis that was, on the first four cars, extended under the rear axle to lower the overall height.

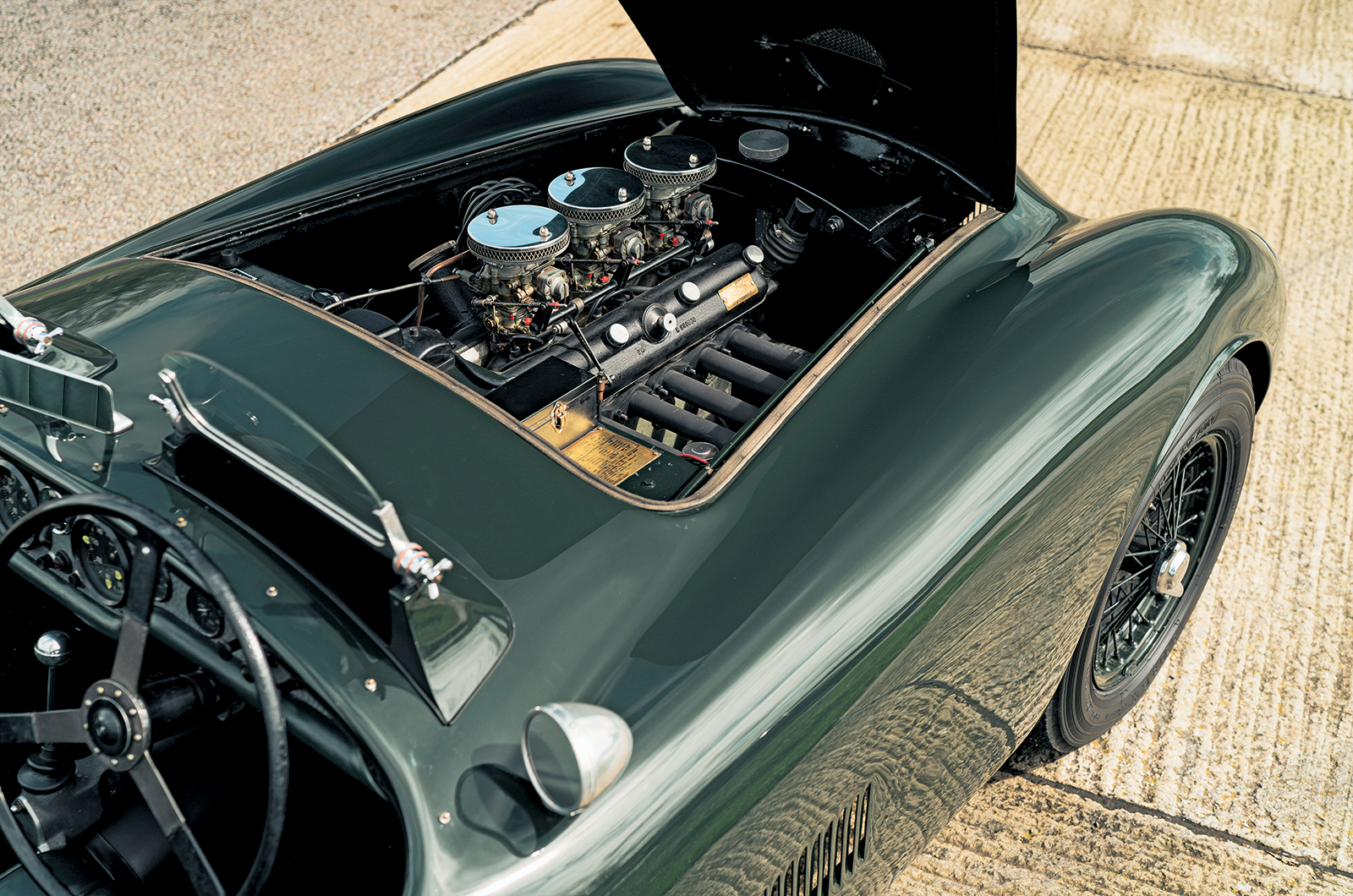

The delicate lines cleverly concealed the tall Bristol engine, needing only a small intake over the high carburettors, and it is universally acknowledged as being the prettiest of the various models – the stylists of the subsequent MGA clearly agreed.

For a car rooted in the 1930s, the Frazer Nash Mille Miglia feels surprisingly modern

All but two cars (including this one) carried the spare wheel in the front nearside wing to give more luggage capacity in the boot – a neat design solution adopted by Bristol four years later on the 404.

Registered YMC 81, this Mille Miglia was completed and photographed in front of AFN in July 1952 before dispatch to a mysterious firm called AS Orr & Co in Manchester (the company was wound up in 1991).

Even more mysteriously, the car was returned to AFN the following May having not appeared in any sporting events.

The Frazer Nash’s dual personality means that you could comfortably drive it home after thrashing it up a hillclimb

That all changed with its next owner, Jack Broadhead.

He would compete with it in rallies along with Peter Reece, who also got to use the car for circuit racing.

At that stage, this particular Mille Miglia didn’t look nearly as stylish as it does today.

Painted Bristol Maroon and with a dark brown leather interior, it was fitted with an Austin rear axle (an item adopted by later Nashes) and wore the same manufacturer’s bolt-on steel wheels, plus an upright afterthought of a windscreen and an even more ill-considered soft-top.

This Frazer Nash has a pleasingly busy competition history

Not that these last two were seen on the car for long.

Apart from the London Rally of 1953 and the following year’s RAC Rally, the gawky windscreen was replaced by a cut-down aeroscreen for serious competition work, such as its circuit debut at Goodwood in the 1953 Nine Hours.

Teamed with Gil Tyrer, Reece brought YMC home in 14th overall and seventh in the under-2-litre group against some formidable opposition – most of which were in their class, which included five Nashes.

The thin-rimmed wheel augments the Frazer Nash’s already accommodating cockpit

Within a month, the Reece/Broadhead pairing had taken a class win in the London Rally with YMC, and 1954 started with a similar programme: the RAC Rally in March, and the Oulton Park Empire Trophy in April, with Reece finishing sixth in the first heat of the latter but retiring from the final.

By July and the British Grand Prix at Silverstone, YMC had acquired a set of wire wheels and the engine had been uprated to BS1 specification.

Not that it resulted in success – the Nash failed to finish – and by the end of the year the MM’s frontline duties as a racing car were over.

A simple set of dials adorn the Frazer Nash’s exquisite dashboard

Numerous keepers followed, but it was in the mid-’80s, when owned by keen Nash fancier Frank Sytner, that Mille Miglia chassis 166 was reinvigorated with a new dark-green paintjob and a matching leather interior.

At some stage the wire wheels were painted the same deep green.

No two Nashes are the same – as a works brochure proudly states, ‘all bodies are Frazer Nash designed, built and finished, entirely by hand at our works’ – but of the 11 true Mille Miglias, YMC 81, in its current livery, is one of the most handsome.

The gearbox is a minor weakness in the Frazer Nash Mille Miglia’s near-perfect package

The earlier cars looked squashed, with incoherent front-end styling, but by the end of production, the craftsmen at the Falcon Works had perfected their art with this example, one of two ‘wide-bodied’ cars.

This not only improved the overall proportions, but also gave the cabin more room.

The 64-million-dollar question was always: ‘Does it drive as well as it looks?’

In short, better.

Few people got to find out in period, and just as few get the chance these days, so it is an illuminating morning when I finally get behind the wheel of my first Frazer Nash.

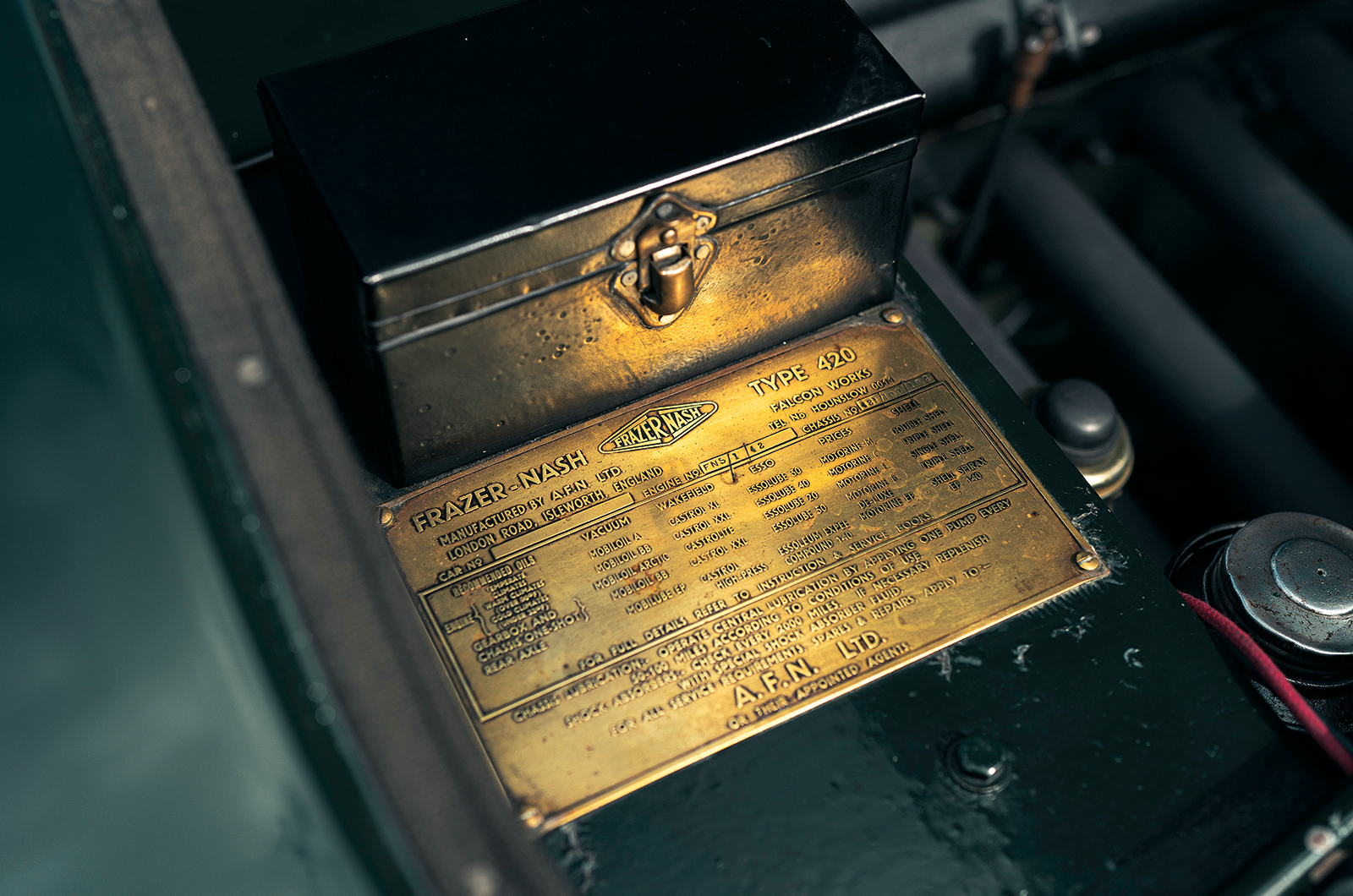

The chassis plate documents the morphing of Frazer Nash into AFN

Slipping into the cockpit is much the same as putting on a suit jacket – I don’t have to look in a mirror to know it fits perfectly.

Unlike in so many cars of the era, and aided by the cutaways on either side, my knees aren’t up against the underside of the dashboard, and my long legs are amply accommodated in the footwells of the roomy but homely cockpit.

The pedals are close, as you’d expect of a competition car, yet not so tight that they can’t be operated with a sensible brogue.

The 2-litre Bristol engine sounds great, especially above 4000rpm

Straight ahead there is the most wonderful, thin-rimmed steering wheel in front of an engine-turned dash that again delights with its symmetry and layout.

It hasn’t even fired up yet and already I’m smitten.

I haven’t had a lot of experience of the 2-litre Bristol engine, yet I’m blown away by just how great it is.

The three twin-choke Solex carbs deliver without fuss, whether hot or cold, and once you get it above 4000rpm it just sounds glorious.

‘Weighing in at 1850lb, everything is light, precise and beautifully balanced’

It’s never going to pin you back in your seat, but the combination of torque, smooth power delivery and plain driveability makes it feel quite modern – and certainly not a product with its roots in the 1930s.

In fact, that’s the overwhelming impression of the Mille Miglia once on the move: it feels 10 years younger than its true vintage, and much closer to a well-built Lotus of the late 1950s than its contemporaries from the likes of Jaguar.

Weighing in at 1850lb, everything is light, precise and beautifully balanced.

The steering is delicate and direct, and there is never any doubt over it pulling up straight or the brakes losing their bite.

The Frazer Nash’s superb road manners are aided by its delicate steering

The handling is exemplary, although being confined to the public highway, we weren’t about to find its limits.

But a spirited early morning cross-country run to, say, Prescott or some other motorsport venue, would be just as exhilarating as the competition itself in the Nash.

Being true to the era of its creation, the ride is relatively soft and not the rock-solid, Tarmac-skimming set-up so beloved by today’s historic-racing brigade, and I’m not sure how well it would fare in such an arena.

If you were desperate to nit-pick, you could be slightly critical of the gearbox in the context of the rest of the package, but it is still streaks ahead of the opposition.

This handsome Mille Miglia was given its dark-green paintjob in the 1980s

No wonder Mike Hawthorn was quoted in The Motor as saying what enormous fun he’d had setting the fastest lap in Len Potter’s Mille Miglia during the 1952 Empire Trophy, whereas in contrast he seldom felt anything other than a combination of terror and boredom at the wheel of any of Ferrari’s faster sports-racers.

As for me, being someone who is never content with just one car and invariably buys too many, too cheaply, the Nash is a revelation.

I suddenly realise where I have been going wrong all these years.

As the late, great Dame Vivienne Westwood used to demand: pay more, but buy once and buy well.

She would have got along well with Aldy.

Images: Luc Lacey

Enjoy more of the world’s best classic car content every month when you subscribe to C&SC – get our latest deals here

READ MORE

Raising the saloon bar: Frazer Nash-BMW 326

Grand tourer supertest: AC Aceca vs Aston Martin DB2 Vantage vs Bristol 404 vs Lancia Aurelia B20 GT

Little gems: Alfa Romeo Giulietta Sprint vs MGA Twin-Cam vs Lotus Elite vs Porsche 356B

Julian Balme

Julian Balme is a regular contributor to Classic & Sports Car and the owner (and driver) of many wonderful classics