They swapped places five times on that final tour, with Walt finally getting the better of his opponent on the last corner and taking the chequered flag by just two car lengths.

In the space of three years, he’d gone from witnessing his first race at the Glen to winning there in a car of his own design.

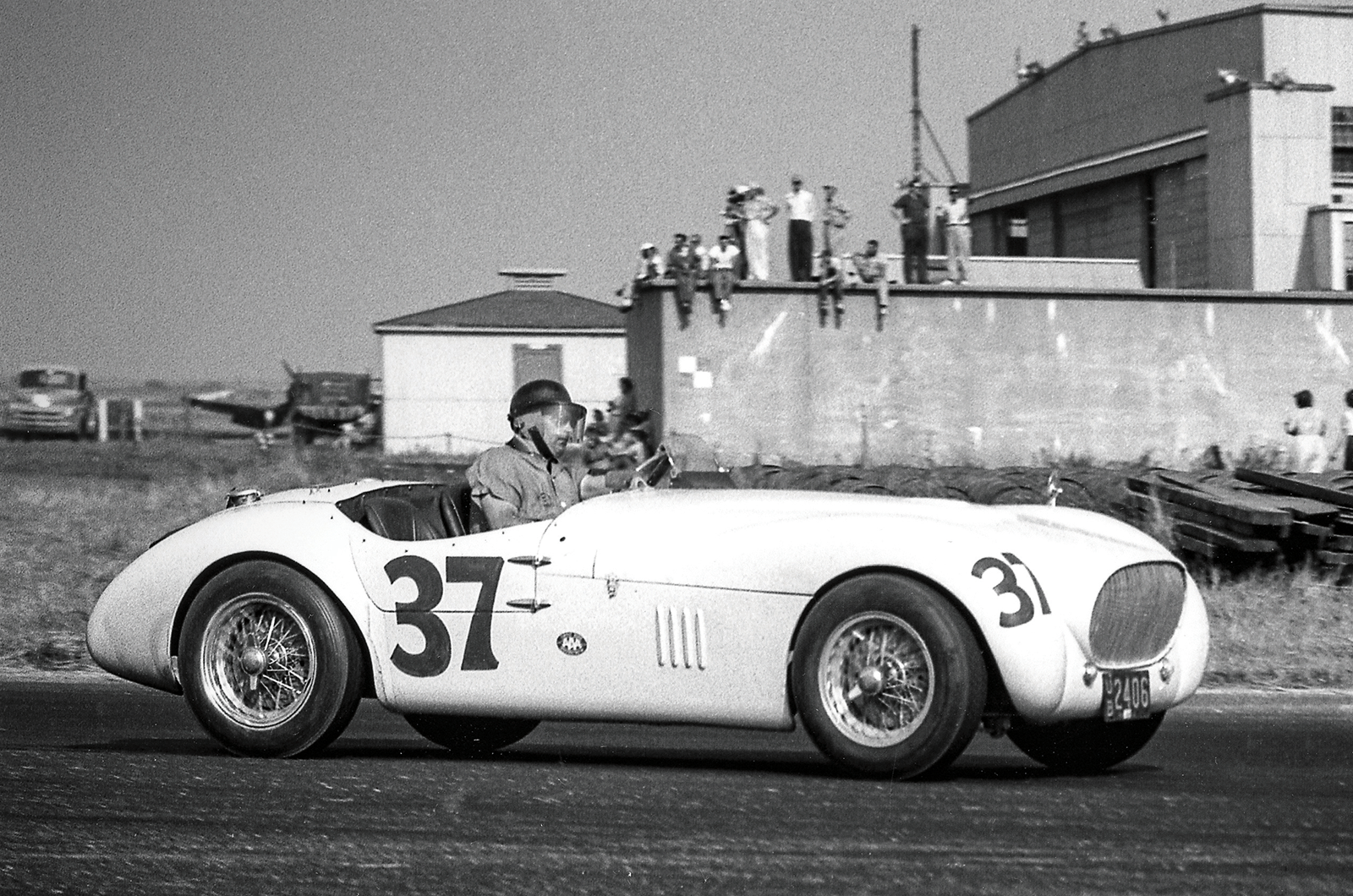

The season wasn’t quite over, and a month later he found himself in Albany, Georgia, contesting an international, FIA-sanctioned sports car race at Turner Air Force Base.

It was a rude awakening.

The Hansgen Special’s small aeroscreen was for racing

The 53-car field was made up of the sport’s finest drivers and machines, and, despite Walt’s desire to compete at the very highest level, it was soon apparent his gallant Special couldn’t hold a candle to a Ferrari 340 Mexico or Cunningham C-5R – clocked at 155 and 156mph respectively down the main straight.

The Special posted just 128mph, 20mph shy of the C-types.

It was a harsh reality check, and only Hansgen’s tenacity enabled him to finish the 250-mile race 10th and third in class.

He needed a faster car and, obsessed almost to the point of addiction, he remortgaged his home and bought Gregory’s deep-blue C-type.

The Hansgen Special on Bicester Heritage’s test track

By way of nothing more than a promise and a handshake, the Special found a new home with Paul Timmins, Walt’s friend and fellow racer.

He painted the wings dark blue and, more often than not, ran it with the full ’screen.

He was always there or thereabouts through 1954, and often made the podium, but he was never in danger of winning a race outright.

His perseverance did, however, win the admiration of his contemporaries, because the Special’s tricky handling was previously judged to only have been tamed by its creator.

The Hansgen Special’s side-exit exhaust pipes are cooled by a louvred alloy panel

Tragically, in March 1955 – and before he could conclude the car’s purchase – Timmins was killed in a road accident in west Pennsylvania in his MG TD.

For the following 11 years the Special served as a weekend road car for its next keeper, George Sterner.

He then sold it to a JD Iglehart who, apart from painting it blue, would contest the odd hillclimb when it wasn’t on display in the Watkins Glen museum.

He kept the car until 1983 when it was bought by Bob Millstein, proprietor of Briarcliff Classic & Imported Car Service, who had seen it run in period and was determined to preserve it as Walt raced.

The spare wheel sits proud of the Hansgen Special’s tail

A keen competitor, Bob contested more than 150 events without incident with the back-to-white roadster, most happily at Lime Rock and the car’s spiritual home, the Glen.

It was another 31 years before the Special found a new keeper in leading US Jaguar expert Terry Larson.

Conscious of the car’s importance, four years ago Terry contacted Jaguar specialist Pendine Historic Cars to see if it could find a suitable custodian.

Swiss-based collector Dr Christian Jenny, a regular visitor to the Bicester Heritage-based firm, was enthralled by the roadster and, though not an active competitor, took on the Hansgen with the aim of bringing it to Europe for an appearance at the Goodwood Revival.

‘Compared to the Jaguar C-type the Hansgen Special feels less refined, though it is far from a junkyard bitsa like some contemporaries’

Despite decades of racing in the US, a stage such as the Freddie March Memorial Trophy – and more stringent FIA regulations – demanded another level of preparation.

Thankfully, the team included David Brazell, a first-rate engineer, highly sympathetic restorer and fan of all things 1950s Jaguar.

For him, working on a car as significant as this was an honour.

Complying with the European rules was not without its challenges, foremost being adding an original four-speed Moss gearbox.

The Jaguar-based Hansgen Special took 14 months to build

Another change involved fitting a Salisbury limited-slip diff, as used by competition Jags of the period, in place of the locked rear with which it arrived from the USA.

But as the team got deeper into the project, it found that reducing the amount of slip helped the handling.

“The expectation is that the car will perform somewhere between an XK and a C-type, and that’s exactly what it does,” says David.

“It’s softer and sits higher than other cars on the grid.”

Two fuel-filler caps lead to the 50-gallon tank

“The big frontal area doesn’t aid straight-line speed,” he continues, “but it handles well, changes direction predictably and, with the slipper, it’s not so inclined to be steered from the rear.

“A nice all-round sports-racer, in which you can charge around Goodwood for 50 minutes before driving to the pub.”

Compared to the C-type, the Hansgen feels less refined, though it is far from a junkyard bitsa like some US Specials of its day.

For a homebuilt, it is remarkably sophisticated, but the all-round quality of the factory car surpasses it in every relevant area.

Room for two in the Hansgen Special racer

Both weigh around the same yet, whether it’s unconscious bias due to the car’s styling, the ‘C’ feels more lithe and nimble.

It probably doesn’t help that you sit high and more exposed in the Special, with the steering wheel at a much flatter angle.

Mechanically they are more or less identical, but, again because of your proximity to the ground, the C-type feels quicker and inspires more confidence through the corners.

For the two-driver Goodwood Nine Hours re-enactment at the 2023 Revival, the Special was piloted by seasoned hands Peter Hardman and Andy Middlehurst.

Rusty Hansgen is reunited with his father’s creation (left); Peter Hardman pushes the Special through the chicane at the 2023 Goodwood Revival

The team was joined in the paddock by two distinguished visitors who had flown in from Texas for the occasion: Walt’s son, Rusty, and grandson, Ashley.

“I was too young to see the Special race,” Rusty recalls. “The first car I really remember was the C-type.

“My sister Beverly and I would fight over who got to ride as passenger on the way to the track.

“I did see the Special when Bob raced it, and he even let me have a go at Lime Rock.”

The Special came about as a result of Walt Hansgen’s dogged determination

A thrilling day ended with the sun going down as the roadster came home 16th.

“It was great to see it run,” says David, “and Peter set a 1 min 37 secs lap – slightly faster than one of the more original C-types.

“But the highlight was definitely having Rusty and his son there.”

For a team so thoroughly embedded in the history of the car and its creator, it was the perfect end to an epic and emotional journey.

Images: James Mann

Thanks to: Pendine

Walt Hansgen’s journey to the top

Hansgen (left) shared Cunningham’s Maserati T151 with Bruce McLaren (right) at 1962’s Le Mans © Getty

The Hansgen Special worked on several levels for Walt.

It gave him a vehicle with which to truly compete, and to showcase his obvious ability behind the wheel of a competitive car.

This latter factor would be important in the development of his career because, by the mid-’50s, wealthy American owners were looking to the likes of Walt to pedal their entries in the fast-growing arena of sports-car racing.

Within barely a year of moving the car on to Paul Timmins, he was piloting numerous front-running entries and on the launchpad to a stellar decade of international racing.

Hansgen’s big break came in early ’56 when, after driving a factory Corvette at Sebring to a class win with John Fitch, he embarked on his debut professional partnership, racing a customer Jaguar D-type for a firm called Auto Engineering.

In his first encounter with the trio of factory-spec Ds campaigned by Briggs Cunningham’s team, he saw them all off with a less-developed version of the same car.

The US team’s patron predictably wooed Walt into driving his white-and-blue entries for the rest of the equipe’s existence.

Sliding the Jaguar 3.4 to a British Saloon Car Championship Class D win at Silverstone, 1958 © Getty

The association would lead to Hansgen not only becoming the team’s lead driver, but it would also settle his financial worries.

To get around him being seen as a ‘paid’ driver by the SCCA, Cunningham bankrolled a Jaguar dealership and fuel station for Hansgen in New Jersey, further establishing his association with the marque.

Walt’s loyalty to the American sportsman and the British manufacturer led to him campaigning not only D-types, but also Lister-Jaguars and the last of the factory line, E2A.

He even raced Mk1 and Mk2 saloons, netting victories at Sebring, Silverstone and Riverside.

By the time of Walt’s tragic death in a 7-litre Ford GT40 MkII at a rain-soaked Le Mans on the first day of testing in ’66, he had contested events in just about every type of car: Formula Junior, F1, Indy, Can-Am, NASCAR, sports cars – the variety and number were limitless.

His wife Bea, although not a fan of his chosen career, meticulously kept scrapbooks, totalling in excess of 900 pages, of all his racing exploits.

By the time of that fateful day in France, behind the wheel he’d gone from being an aggressive rough diamond to the consummate professional.

Enjoy more of the world’s best classic car content every month when you subscribe to C&SC – get our latest deals here

READ MORE

The all-American hero: driving Lance Reventlow’s Scarab sports-racer

The hero to zero and back tale of this Jaguar D-type

A Cunningham plan: amazing Cadillacs recreated

Julian Balme

Julian Balme is a regular contributor to Classic & Sports Car and the owner (and driver) of many wonderful classics