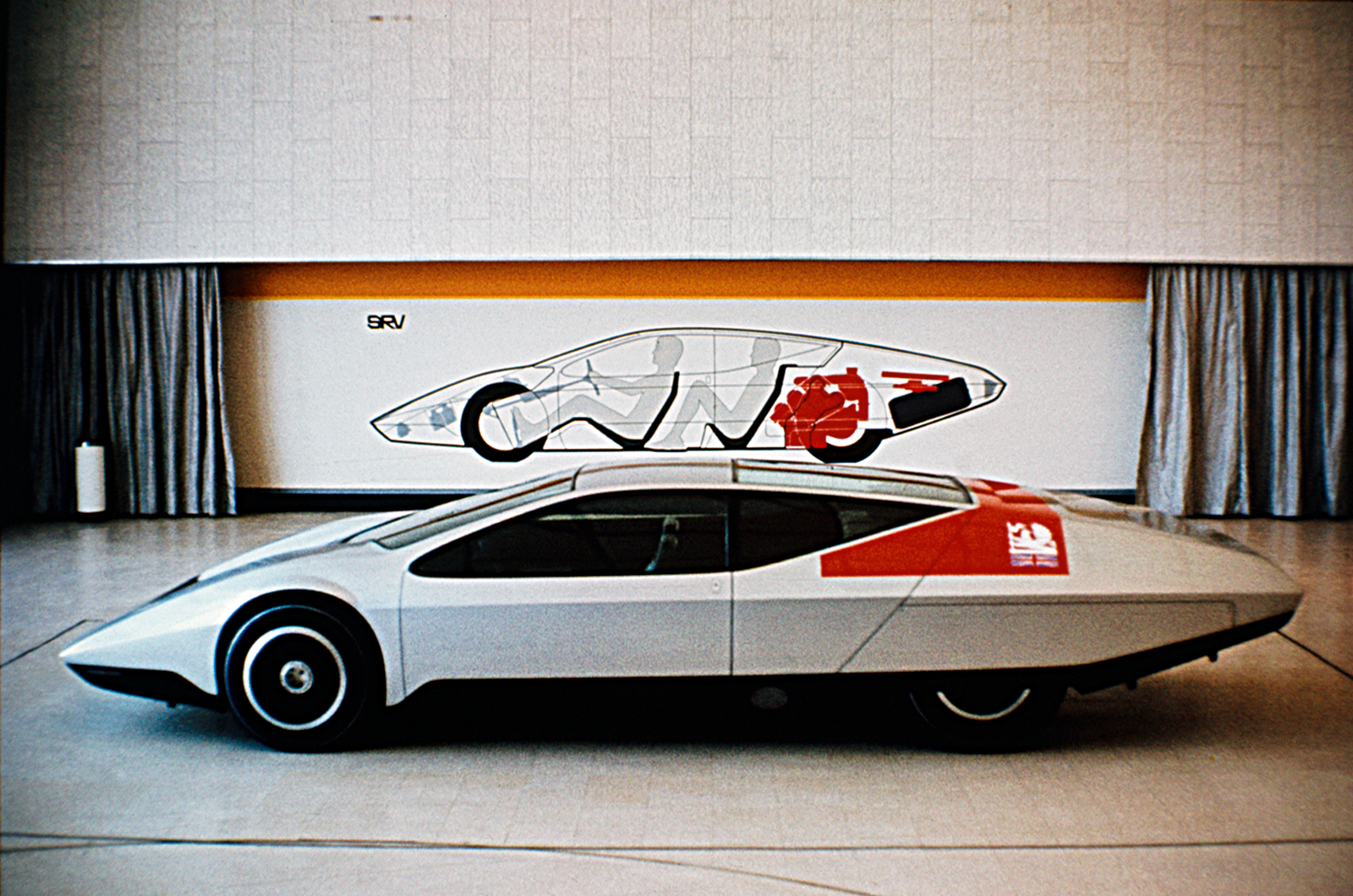

Into three figures, the car feels a touch unstable, the wheel becoming light as the nose starts to lift. No problem; ease back the lever in the door to tweak the front spoiler, press a couple of buttons to reduce the rear ride height and pump 20 litres of fuel into the forward bag tanks.

The trim gauge says we’re riding level, so plant the throttle and the boost needle flickers as the turbocharger spools up, noisily forcing fuel and air into the compact twin-cam motor.

Except we aren’t on an empty runway, we’re in a studio in Middlesex; the speedo needle is resting firmly on its lower stop, and those whooshes and whistles are entirely self-made. “Er, could you get out now?” asks photographer Spinney.

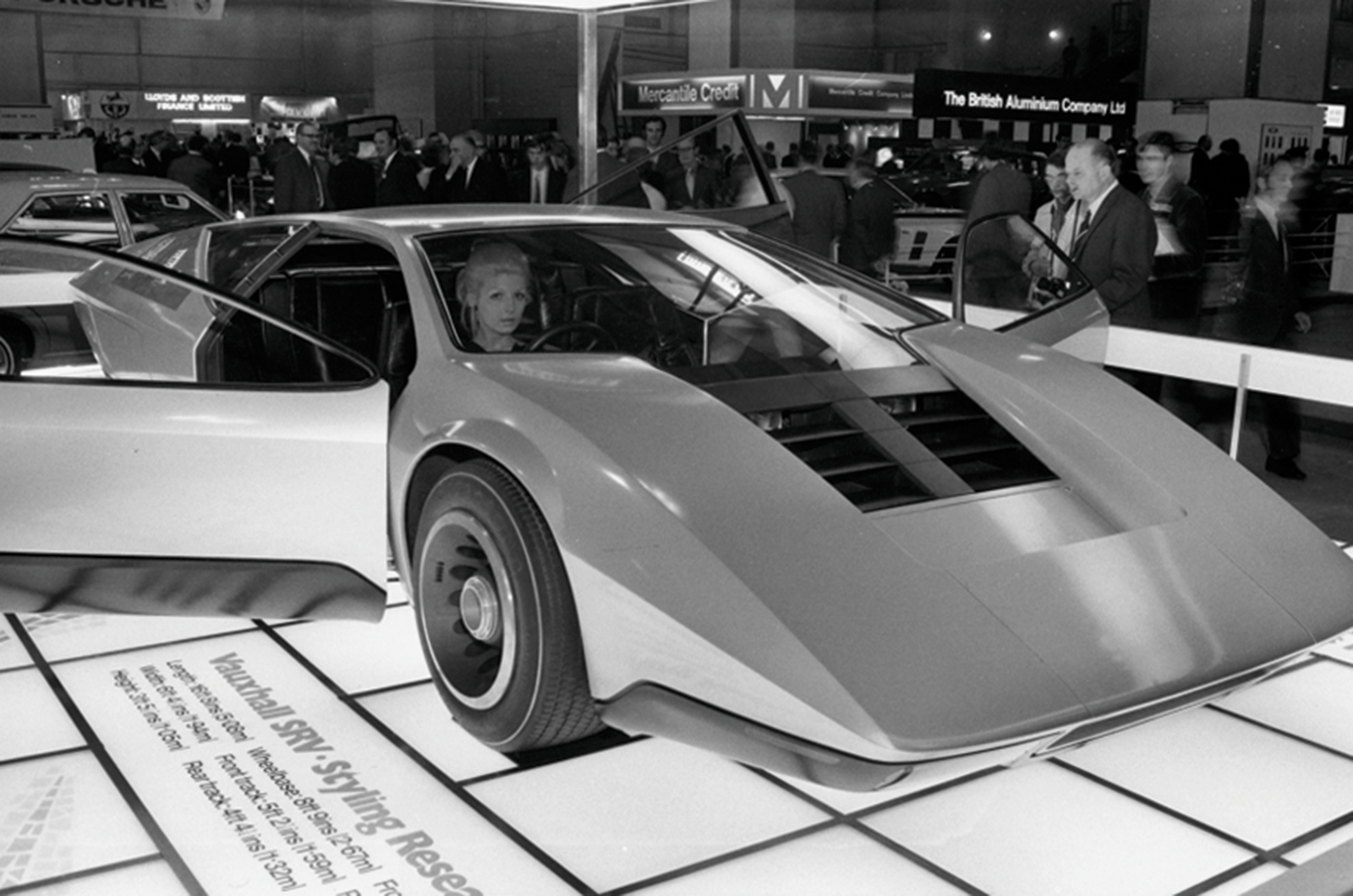

It’s hard not to drift into fantasy when you clamber aboard this dramatic, aerofoil-shaped concept car, but the clue to its silence lies in the name: Styling Research Vehicle (SRV).

Not much functional engineering went into this vision of the future, yet it feels remarkably complete. And exotic, which is why it comes as rather a shock to find Vauxhall’s unmistakable Griffin plastered on the car’s flanks.

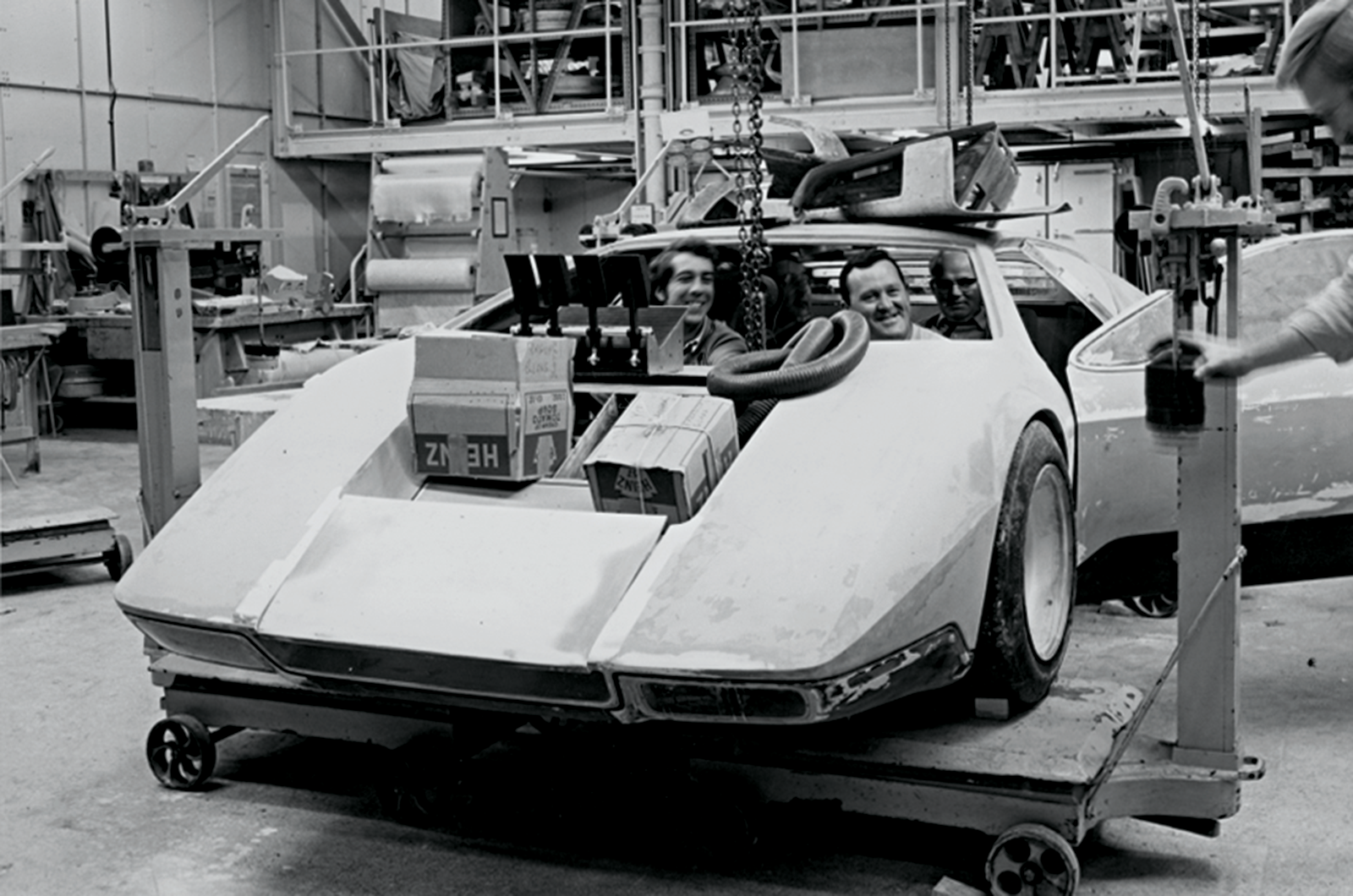

Clockwise from top: four-seater reveal creates a ‘wow’ moment; packaging drawing shows clever internal layout; Stephenson designed parallelogram hinges for rear