It may seem odd today to consider the antiquated styling of a Morgan as a hindrance to commercial success – it’s become very much the firm’s raison d’être – but by the early to mid1950s, the square-rigged flat-rad was looking decidedly passé.

A facelift was called for, and with it was born the quintessential Morgan that’s so recognisable today: the so-called ‘cowl-rad’.

First seen in 1953 and mildly reworked in ’54, the reshaped nose and faired-in lamps created a distinctive look that, although far from cutting edge, was noticeably more modern than the previous design.

The cowled rad was introduced in 1953, and set the definitive Morgan style

It remains the Malvern staple some 63 years on: Stuart Blake’s eye-catching yellow 4/4 (a dash replaced the hyphen in ’55) is no oldtimer, but it’s as representative here as any sextagenarian example.

This is the shape that defines most people’s perception of a Morgan.

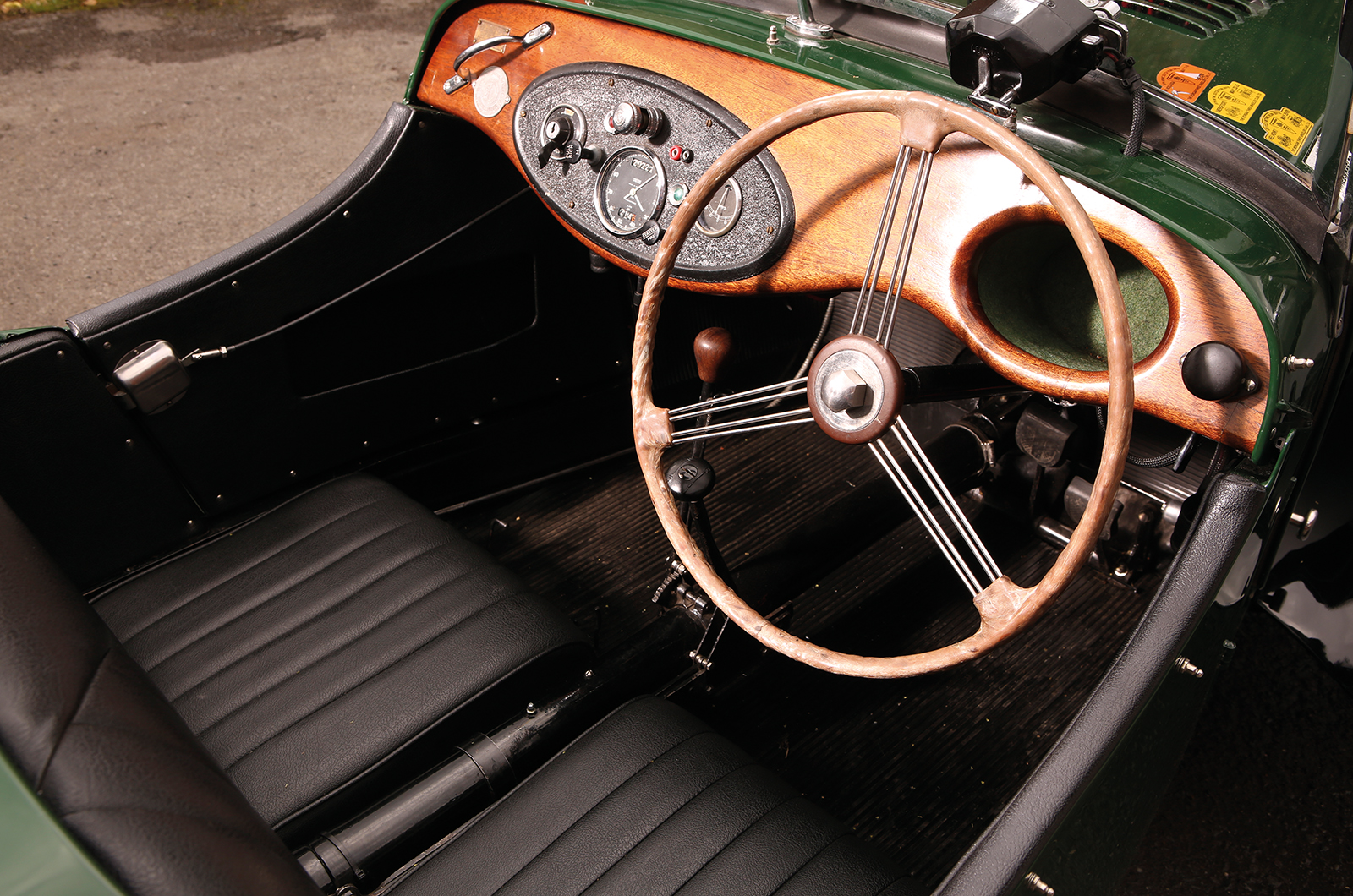

Settle into the cockpit after the flat-rads and the updates are far-reaching. From seats to fascia to trim to steering wheel, it all feels curiously modern, yet the similarities are just as noticeable as the differences.

This feels like a younger version of the same recipe – slicker, quicker, more efficient and no doubt less demanding to own, but with the same inherent appeal of the earlier models.

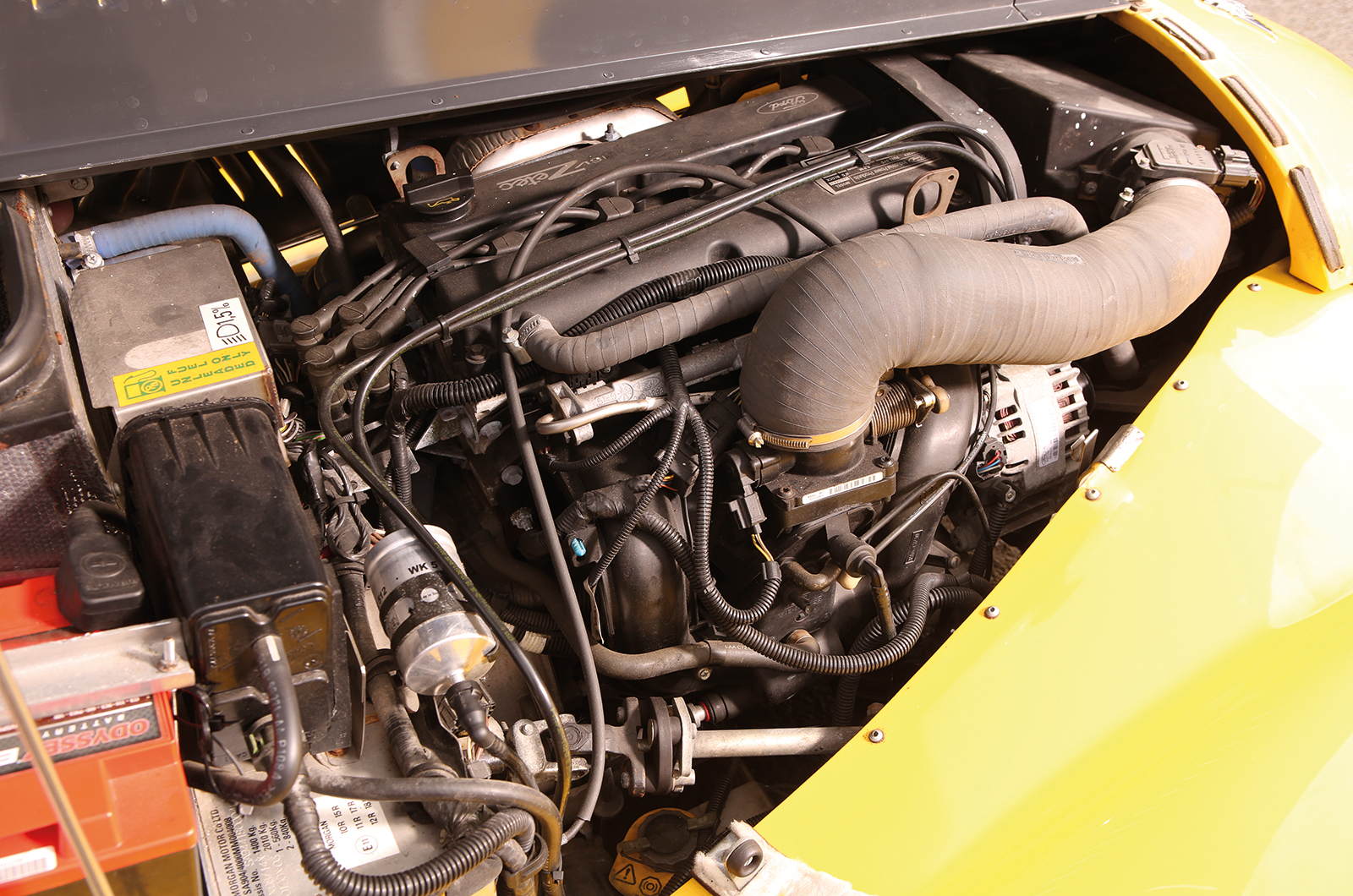

Interior subtly modernised immediately transports you back to the genteel world of mid-20th-century Britain; 121bhp Zetec engine for featured car

There’s a more modern gearbox and powerplant – a 121bhp, fuel-injected, 16-valve, 1796cc Ford Zetec in this car – plus better brakes and wider radial tyres, but the defining characteristics remain unchanged.

You’ve still got the Z-section chassis, the sliding-pillar front and semi-elliptic rear suspension, not to mention the same ash-framed body.

Think of it as a 1930s house with modern creature comforts such as central heating and double-glazing: period charm without the penitence.

Performance is in the brisk rather than blistering category: 0-60mph comes up in 7.8 secs, while top speed is in the region of 110mph, but the 4/4 – the entry-level four-wheeler – is about nimble progress rather than outright pace.

The Morgan Plus 4 Plus was a marked departure for the Malvern brand

If the adoption of the now-iconic cowl-rad was mere titivation, a veritable revolution hit the streets of Malvern in October 1963 in the form of the Plus 4 Plus.

Clothed in a glassfibre bodyshell penned by John Edwards of EB Plastics in Stoke-on-Trent, the inspiration for it came from that firm’s Debonair kit.

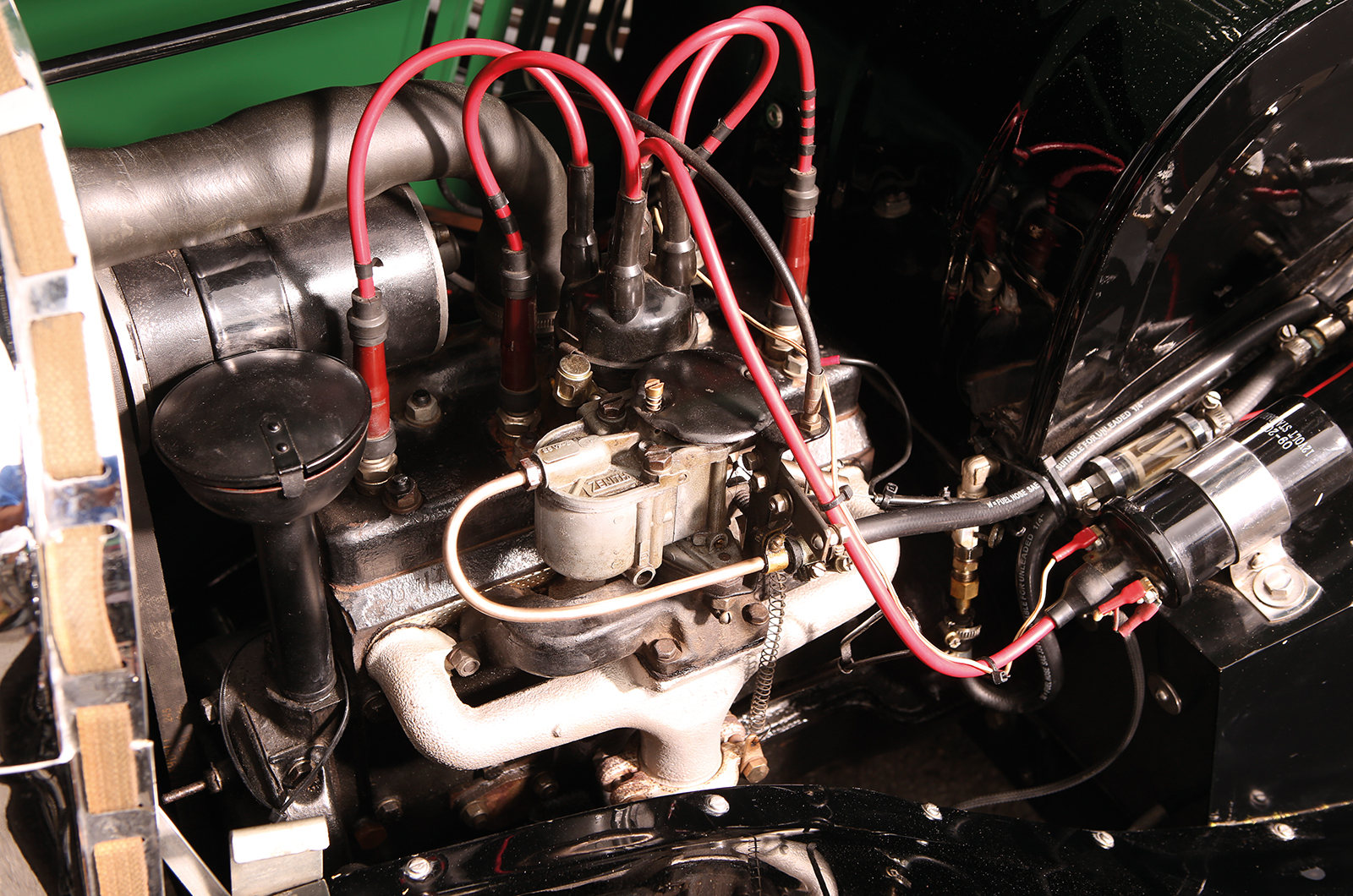

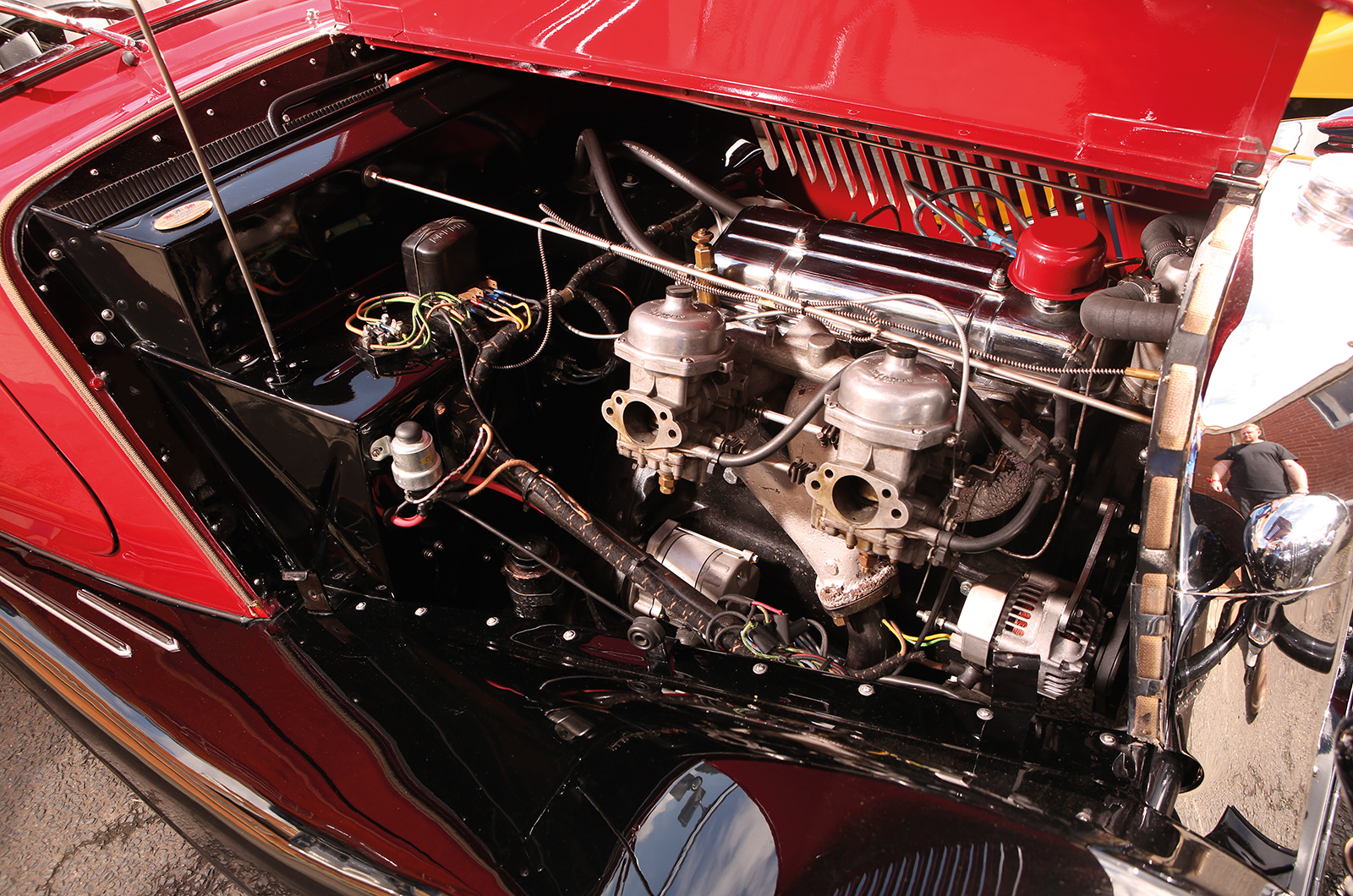

The underpinnings were those of the standard Plus 4 of the day – which is to say a 2138cc, 105bhp, twin-carb ‘four’ from the contemporary Triumph TR4, and Girling disc brakes on the front.

The result is a particularly intriguing vehicle.

From the waist down, it’s strikingly attractive, although the turret-like top and small side windows lend the profile a certain naïvety; it is not entirely resolved, but that makes it all the more fascinating – in much the same way as a Daimler Dart.

The cabin is more spacious; TR4 engine runs on non-standard Weber carbs

The first thing that you notice as you climb in is the remarkable amount of space – plus the absence of a running board to step over.

This is also the first Morgan that doesn’t really feel like one: the full-width body provides occupants with considerably more elbow room, and the architecture of the cabin is very different – to such an extent that you begin searching for familiar Malvern cues.

The sprung wheel, floor-hinged pedals and dials are recognisable, yet the overall effect is anything but. The black fascia and small bucket seats feel more Triumph than Morgan, and you can easily imagine this being a stillborn project to replace the TR3 with a fixed-head GT.

Alas, although the Plus 4 Plus was not quite stillborn, only 26 were built. Improved aerodynamics combined with a kerbweight no greater than that of the standard Plus 4 roadster mean that the coupé is a keen performer, but although the handling was praised by testers in period, the decidedly vintage ride was somewhat at odds with the grand tourer pretensions of the sleek new shell.

Furthermore, at £1276 it was twice the price of a standard Plus 4. The car was doomed to be a commercial failure, which really is a shame – it’s a niche model, but has a very genuine appeal.

This Plus 8 has the wider body that was introduced from 1976

If the Plus 4 Plus failed to convince buyers, for almost four decades the next car in our line-up offered what many considered to be the ultimate Morgan experience, melding an enticing blend of retro style with dramatic punch.

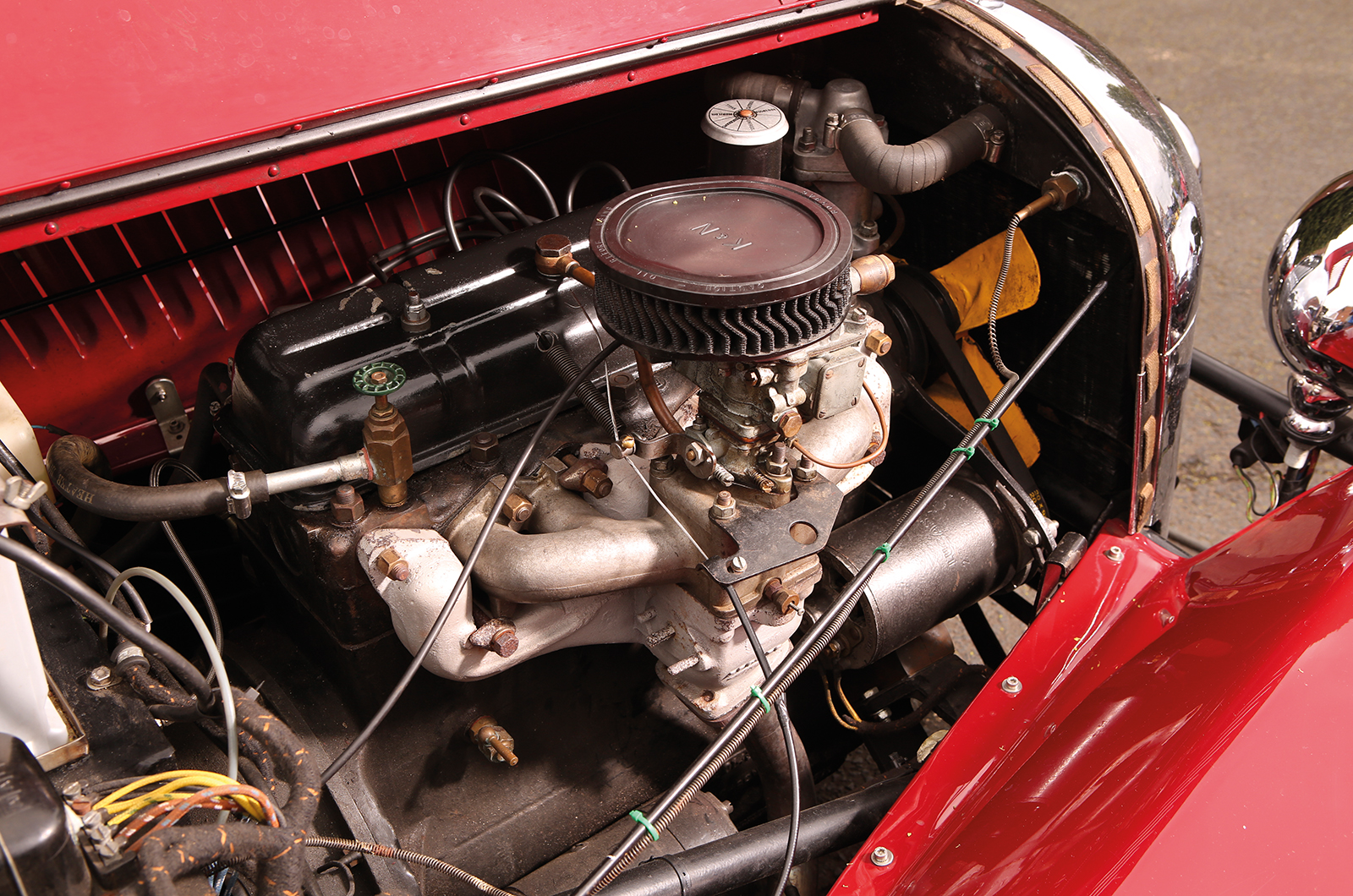

Introduced in 1968, the Plus 8 utilised Rover’s brilliant 3.5-litre, all-alloy V8 in a widened and lengthened Plus 4 chassis to create a well-planted and torque-rich hot-rod that could sprint to 60mph in a touch over 6 secs and on to a maximum of 124mph, making it a seriously fast conveyance.

Regularly updated in line with the engine’s continued development, the Plus 8 would eventually be equipped with a 220bhp, 4555cc, fuel-injected unit pumping out 260lb ft of torque in a flyweight package, but the concept remained unchanged.

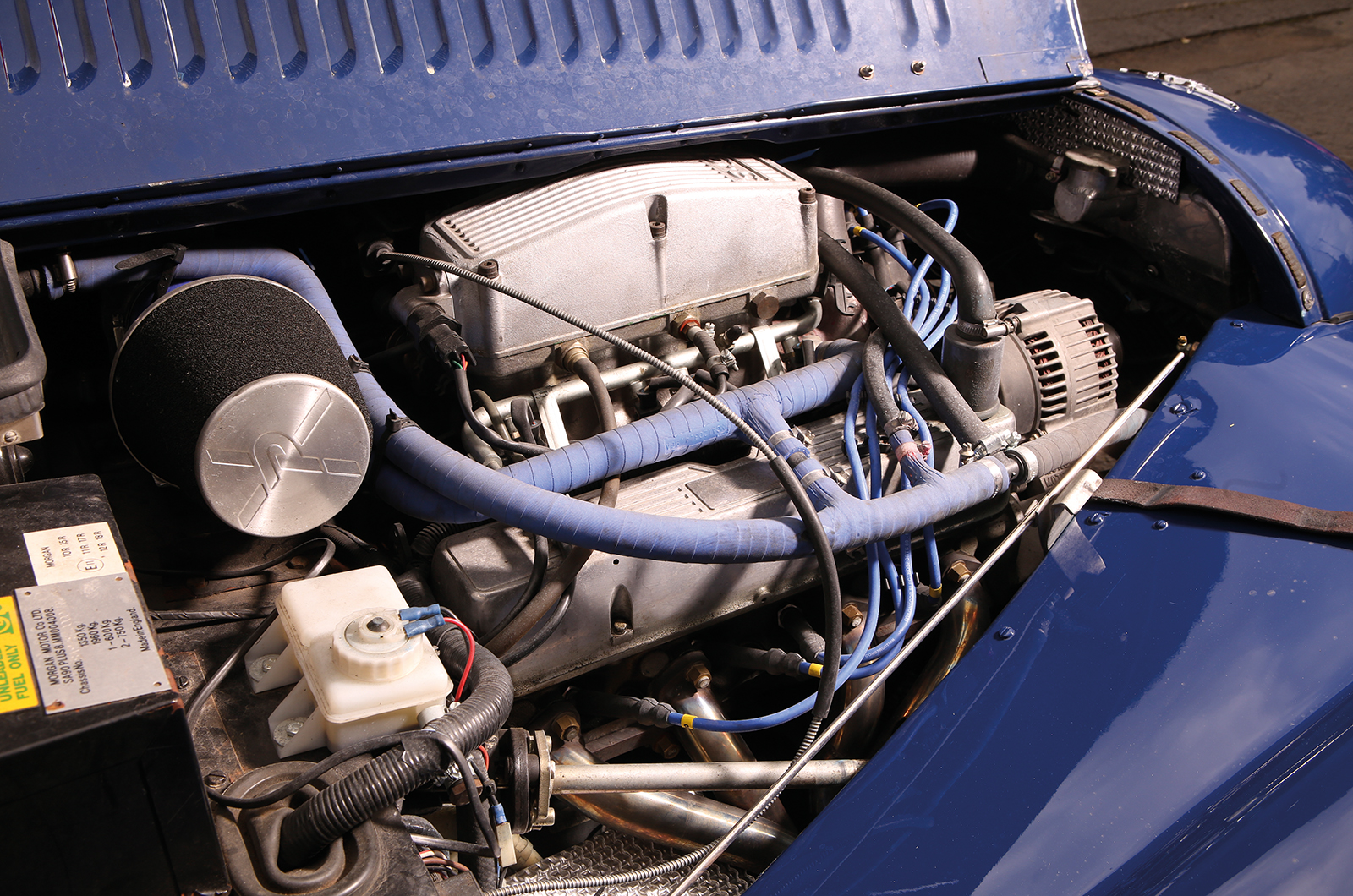

The Plus 8 has a luxurious cabin; various iterations of Rover's V8 were used

This docile dragster was as happy to potter as it was to race for the horizon, but as Motor reported after testing the 3.5-litre version: ‘The usable performance is immense… a reservoir of power can be unleashed from 500 to 5000rpm in any gear to devastating effect,’ adding that, ‘all you hear is the unmistakable burble of a fine small-block V8, which all our testers found addictive’.

It’s little wonder that some 6232 found buyers over the course of the model’s 36-year production life.

When the Plus 8 was finally pensioned off in 2004, Morgan was left with a vacuum to fill: a traditional sports model with greater performance than the four-cylinder cars.

The gap was plugged by the Roadster. Powered by a 2967cc Ford V6, it may have lacked its eight-cylinder predecessor’s bewitching woofle, but here was a car that, at 0-60 in 5.4 secs and 135mph, was even quicker.

A brief drive in Brian Cowell’s immaculate red example is enough to confirm that the Roadster’s improved weight distribution also made it slightly more nimble.

The Aero 8 was the first model to use Morgan’s new aluminium chassis

Some may have lamented the passing of the old V8, but for those seeking ultimate performance – and to whom the Roadster was two cylinders short of a picnic – a radical new beast had sallied forth from the factory two years earlier.

Enter, stage left, the Aero 8.

By the turn of the 21st century, pundits could have been forgiven for believing that Malvern would follow the same by-then-archaic recipe for the rest of time – it was, after all, decades since the last radically different model, the Plus 4 Plus, which had bombed.

It came as a shock to many, then, when the all-new Aero 8 blasted onto the scene at the Geneva Salon in 2002.

Far more than a restyle, this brainchild of Charles Morgan was developed from the company’s successful GT2 race programme and it ushered Pickersleigh Road into the modern era.

Clothed in an intriguingly retro superformed aluminium suit (a process not unlike vacuum-moulding with semi-molten metal), the chassis was all new, boasting the type of bonded and riveted construction more commonly associated with the aviation industry; the Aero moniker really is quite apt.

Inside, the Aero 8 blends retro and modern; stylish script

Power, meanwhile, was courtesy of the Bavarians, in the form of BMW’s superb 4398cc 32-valve V8, while sliding pillars and leaf springs were finally abandoned in favour of wishbones all round – bestowing the car with a previously unheard-of ride quality.

With its wind-up windows – electrically operated, at that – and other mod-cons, this futuristic flight of fancy set the cat among the Malvern pigeons.

The interior is a mix of the borrowed and the bespoke and, compared to the bleakness of mainstream cabins of the day, is a stunning fantasy world of machine-turned aluminium.

Coupled with the extensive use of hide and ash detailing (the latter is actually structural – the body still incorporates a timber frame), it has the feel of an expensive yacht, but there’s nothing nautical about this car’s performance.

Launched with 286bhp, it was upgraded during its life to 333bhp, meaning that it could blast from 0-60 in 4.5 secs and top 160mph.

The race-bred handling also received praise, with Autocar describing the cornering ability as ‘close to ideal, with bags of grip, very little roll and a neutral stance even at extreme speeds’. If your idea of a Morgan is an antique built by blacksmiths, you must try one of these.

The Aeromax's rear view is particularly outrageous

For all the Aero 8’s brilliance, the controversial styling was always a stumbling block, but the same criticism could never be levelled at the sensational Aeromax, which made its debut at Geneva in 2005.

Based on Aero 8 underpinnings and originally commissioned by Morgan fanatic Eric Sturdza, this latter-day Deco masterpiece by stylist Matt Humphries melds Bugatti Atlantic and Corvette Sting Ray with tropes from the trad models, and is guaranteed to turn heads wherever it goes – even in Malvern, where Morgans seem as commonplace as Fiestas.

The cabin echoes the Aero 8, with vast swathes of leather (including a fluted headlining that snuggles up either side of a central roof member), plus similar alloy and timber detailing.

Aside from the modern wheel, which looks rather out of place, it feels beautifully tailor-made. The ambience is not unlike a roomier version of the short-lived Marcos TSO, and the Aeromax is almost as rare – just 117 were built.

That it remained a strictly limited-edition special is cause for some considerable sadness, because it’s an incredible machine.

However, inside the Aeromax cossets occupants; the BMW V8 gives epic performance

‘Ours’ is an automatic (a six-speed manual was also available) and will cruise along with remarkable docility, but a muted rumble from the exhausts leaves you in no doubt that some serious performance is on hand.

Tickle the throttle and the 362bhp, 4.8-litre fastback will roar all the way to a top speed well north of 160mph, while the chassis dynamics are very much akin to the open car, which is no bad thing.

With the demise of the Aero 8 in 2009, and its fixed-head cousin a year later, for a moment Malvern’s creative flourish appeared to have fizzled out: the range was reduced to the traditional fare of 4/4, Plus 4 and Roadster, and Pickersleigh Road appeared to have reverted to what – in the eyes of the traditionalists – it did best.

But then, in 2011, along came a brace of new models that proudly drew from the company’s illustrious heritage, but which were diametrically opposed in their make-up. In the red corner we have the Plus 8, and in the blue corner the 3 Wheeler.

Traditional styling on a newer chassis for the later Plus 8

At first glance, the former looks like more of the same, but don’t be deceived: this is no wide-bodied version of your boggo Moggo.

Beneath the aluminium skin this car is to all intents and purposes an Aero 8, with all the tech that the name implies, including bonded aluminium chassis and wicked amounts of Munich power.

It may lack the slim-hipped elegance of the lesser models – the narrower Morgans have always enjoyed a more resolved shape – but this is a good-looking car, with none of the controversy that surrounded the Aero 8’s styling.

A more roomy cabin than on older models; that famous badge

And what a marvellously beguiling machine it is, blessed with a soundtrack that passes from a deep and suggestive bellow to a spine-tingling howl as the revs climb.

That in itself is enough to seduce the driver, but there’s more: with 362bhp and 370lb ft on tap, it feels blisteringly fast, while the steering is nicely weighted and amazingly direct.

It’s surprisingly roomy, too, but with a cockpit that feels very much like a Morgan should.

The 3 Wheeler brilliantly evokes the original model

If the high power and tech of the Aero generation is too much, the last car in our line-up is very much the antidote.

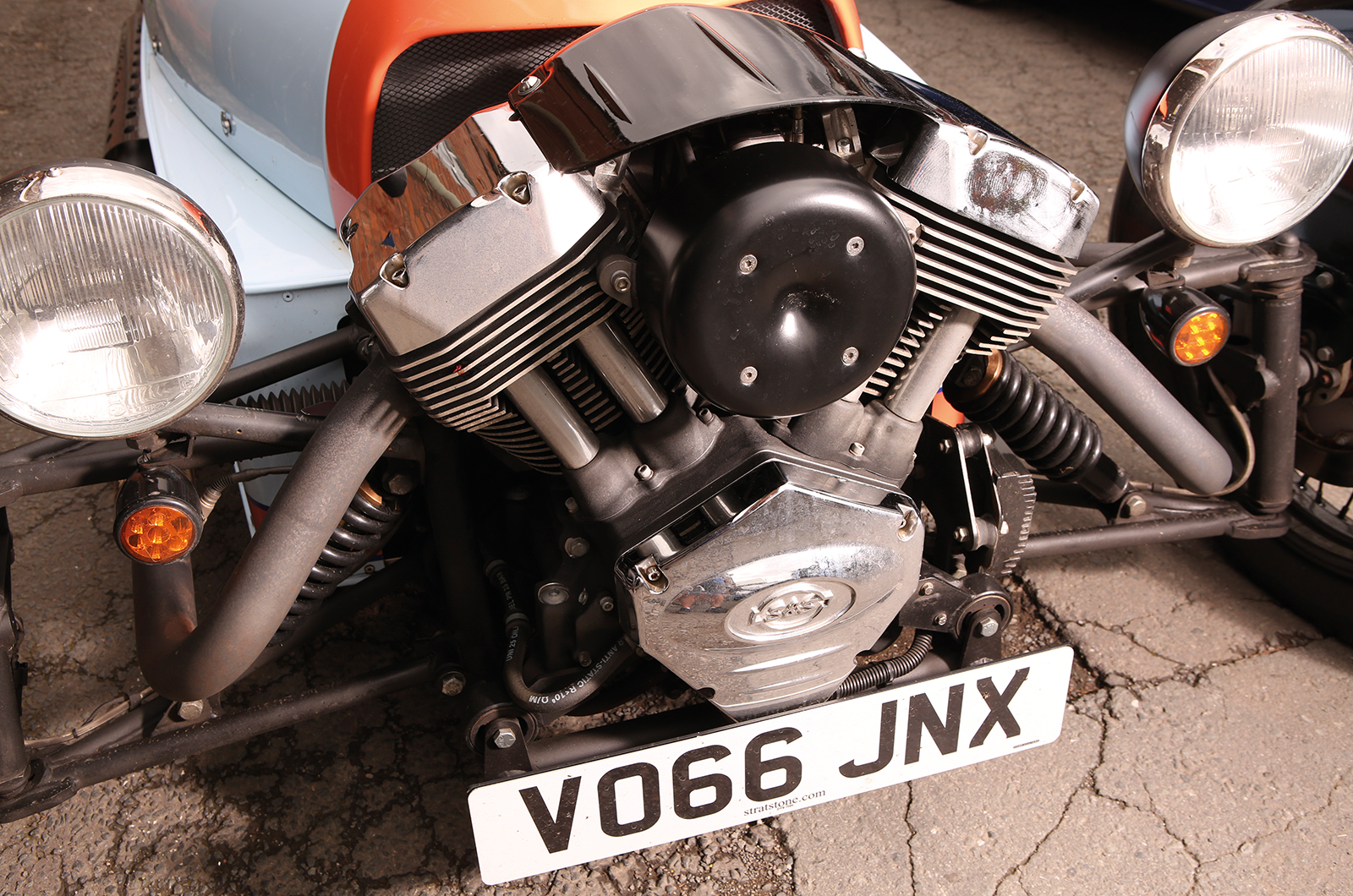

Launched at the Geneva Salon in 2011, the 3 Wheeler is a spectacular homage to the firm’s earliest efforts, and is perhaps the most irreverent two-fingered salute to have emerged from the motor industry in decades, an unsophisticated and joyously impractical machine whose only goal is to make you laugh out loud.

And it certainly does that.

The theatre begins when you drop into the simple cockpit, where – as in its pre-war cousin – the mood is more light aircraft than motorcar.

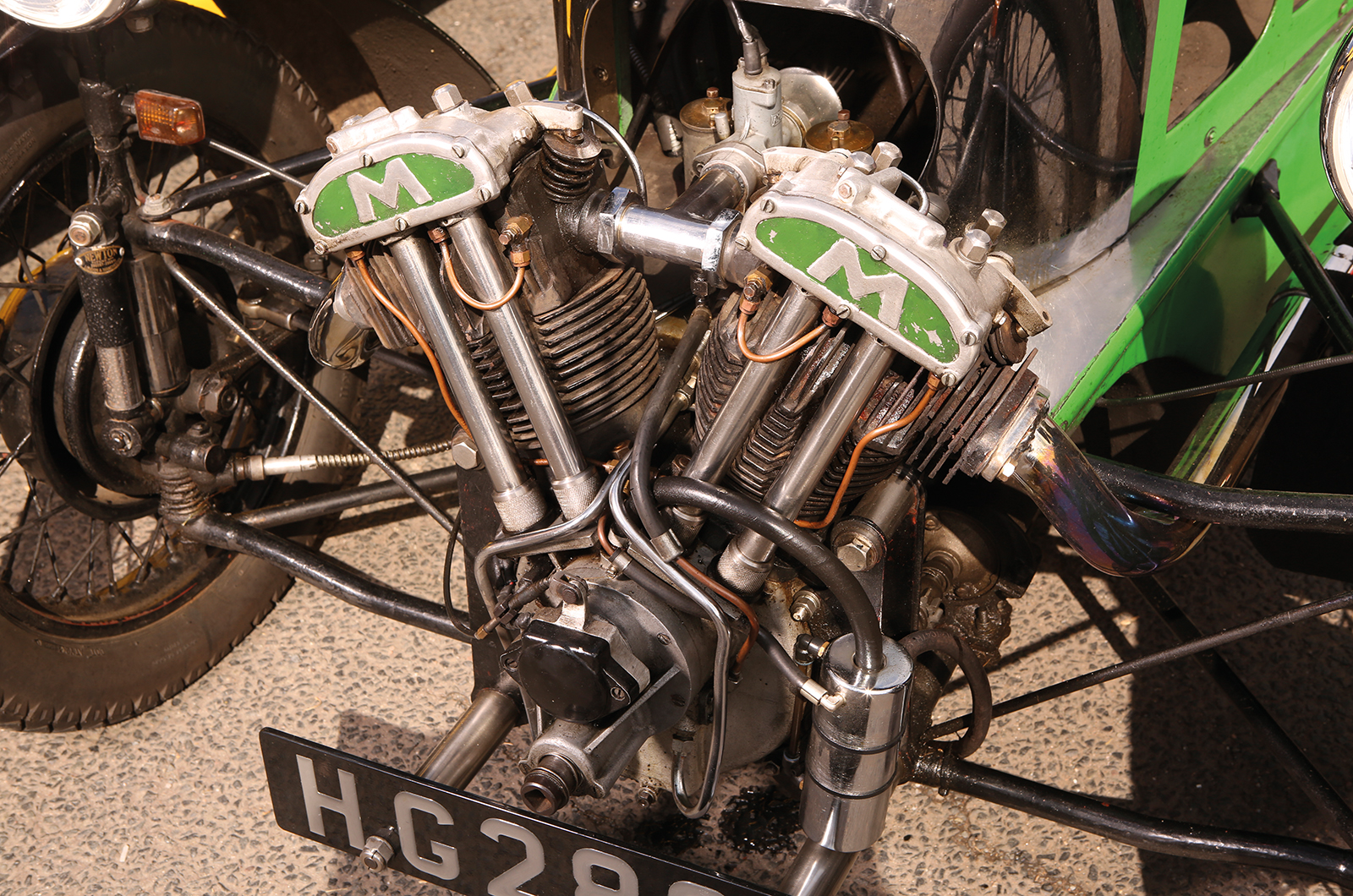

With the ignition on, lift the flap that conceals the starter button and give it a jab; the 1983cc S&S V-twin bursts into life and settles down into a lazy motorcycle chug.

After the earlier three-wheelers, this one is remarkably spacious, although there’s still no room for your right elbow inside the cockpit.

You sit low, and if you’re of diminutive stature you’ll find yourself peering over the scuttle in search of the road ahead, but such considerations ebb away as soon as this eccentric contraption launches you up the road.

The interior might be spartan but it has quilted bucket seats; that thumping V-twin

The massive ‘twin’ doesn’t appreciate pottering in too high a gear, and mini-roundabouts reveal a poor turning circle, but on the right road this is a fantastic place to be.

The Mazda MX-5 gearbox is a joy, the brakes and tiller nicely weighted, the growl from the engine superb.

A few miles are enough to understand why this little tripod has become such a success story for the Worcestershire firm: if Morgans are about driving pleasure, this hits the bullseye.

With such a diverse range, there’s a car here for every occasion, but two in particular leave a lasting impression.

The Aero Plus 8 is an incredible device that provides enormous thrills and a magnificent soundtrack. At the opposite end of the spectrum, the little Super Sports is one of the most intriguing machines I’ve ever encountered. It genuinely fascinated me.

The two are poles apart, but they share an irresistible charm and prove that there’s a lot more variety in Malvern than some might think. Vive la différence!

Morgan: a family business

Henry Frederick Stanley Morgan – known as HFS or ‘Harry’ – was born on 11 August 1881 in Moreton Jefferies, near Malvern.

An early interest in engineering led to an apprenticeship with the Great Western Railway, but he left at the age of 23 to establish ‘Morgan & Co’.

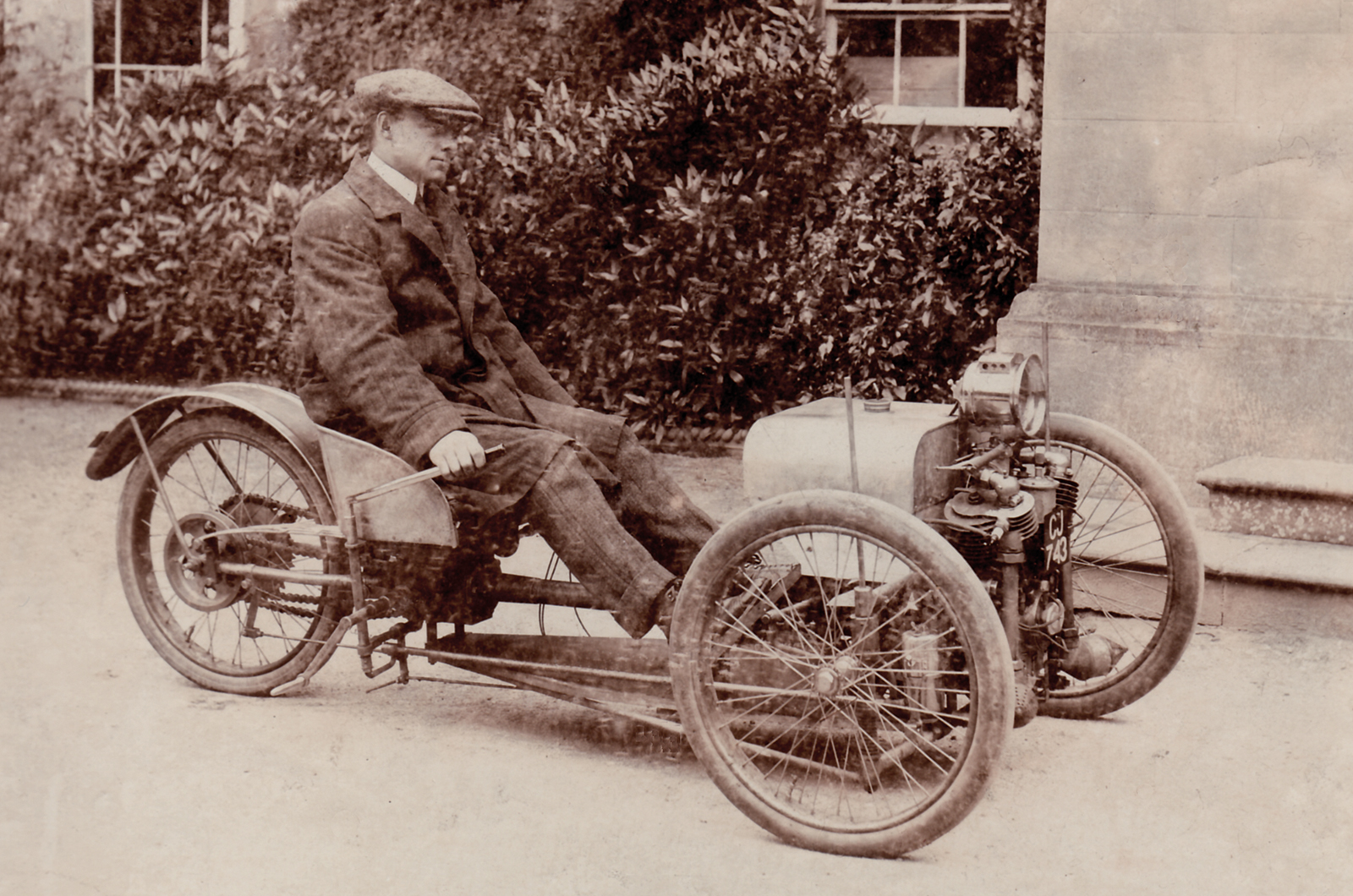

The business offered vehicle repairs, sales and even chauffeur-driven hire cars, then in 1909 HFS built his own three-wheeler. The single-seater Morgan Runabout used a Peugeot twin-cylinder engine, and was first displayed at the 1910 International Motor Cycle Show.

The warm reception it received encouraged him to put it into production. The first Morgan agency was the Harrods store in Knightsbridge.

The three-wheel single-seater Morgan Runabout built by HFS in 1909 © Morgan Motor Company

In 1912, HFS married Hilda Ruth Day, and in 1919 a son, Peter, joined their four daughters.

By 1935, HFS had moved the family to Berkshire and delegated much of the day-to-day business to his works manager, George Goodall.

He died at the age of 78 in 1959, the year after Peter had become MD.

It was Peter’s determination that led to the marque surviving and he remained at the head of Morgan until he died in 2003. Peter’s son Charles later had a stint as managing director, but left in 2013.

Images: Tony Baker

SPEC SHEETS

| Car |

Super Sports MX2 |

F Super |

Plus 4 |

4/4 Zetec |

Plus 4 Plus |

| Sold |

1933-’39 |

1933-’52 |

1950-’69 |

1993-’06 |

1964-’67 |

| Built |

N/A |

1216 |

6853 |

N/A |

26 |

| Construction |

Tubular steel chassis, steel panels over ash frame |

Z-section steel chassis, aluminium/steel panels over ash frame |

Z-section steel chassis, steel/aluminium panels over ash frame |

Z-section steel chassis, steel and aluminium panels over ash frame |

Z-section steel ladder chassis, glassfibre body |

| Engine |

Matchless ohv 998cc V-twin; 39bhp @ 4600rpm |

Cast-iron, 1172cc sidevalve ‘four’; 22bhp @ 3500rpm |

Cast-iron, 2088cc ohv ‘four’; 68bhp @ 4300rpm; 112lb ft @ 2300rpm |

Iron-block, alloy-head, 1796cc ‘four’; 121bhp @ 6000rpm; 115lb ft @ 4500rpm |

Cast-iron, ohv, 2138cc ‘four’; 105bhp @ 4750rpm; 128lb ft @ 3350rpm |

| Transmission |

3spd manual, RWD |

3spd manual, RWD |

4spd manual, RWD |

5spd manual, driving rear wheels |

4spd manual, driving rear wheels |

| Suspension |

Independent, by sliding pillars, coil springs (f); quarter-elliptic leaf springs (r) |

Independent, by sliding pillars, coils (f); quarter-elliptics (r) |

Independent, by sliding pillars, coil springs, telescopics (f); semi-elliptics, lever-arms (r) |

Independent, by sliding pillars (f); live axle, leaf springs (r); telescopic dampers (f/r) |

Independent, by sliding pillars, coil springs, telescopics (fr); live axle, semi-elliptic leaf springs lever-arm dampers (r) |

| Steering |

Epicyclic reduction |

Epicyclic reduction |

Cam gear |

Recirculating ball to 1999, rack and pinion to 2006 |

Cam gear |

| Brakes |

Drums |

Drums |

Drums |

Discs/drums |

Discs/drums |

| Top speed |

73mph (MX4) |

74mph |

85mph |

111mph |

110mph |

| Price new |

£128 |

£132 |

£652 |

£16,256 |

£1,275 |

| Price now |

from £30,000 |

from £30,000 |

from £30,000 |

from £25,000 |

£100,000+ |

| Car |

Plus 8 |

Aero 8 |

Aeromax |

Aero Plus 8 |

3 Wheeler |

| Sold |

1968-’04 |

2001-2010 |

2008-’09 |

2012-date |

2011-on |

| Built |

6130 |

N/A |

117 |

122 |

c1600 |

| Construction |

Steel chassis, ash frame, steel body panels |

Bonded/riveted aluminium tub, aluminium panels over ash frame |

Bonded/riveted aluminium tub, aluminium panels over ash frame |

Bonded/riveted aluminium tub, aluminium body over ash frame |

Tubular steel chassis, aluminium body over ash frame |

| Engine |

All-alloy, ohv, 3946cc V8; 190bhp @ 4750rpm; 235lb ft @ 2600rpm |

dohc-per-bank, 32-valve, 4398cc V8; 286bhp @ 5500rpm; 324lb ft @ 3600rpm |

dohc-per-bank, 32-valve, 4799cc V8; 362bhp @ 6100rpm; 370lb ft @ 3600rpm |

All-alloy, dohc-per-bank, 4799cc V8; 362bhp @ 6300rpm; 370lb ft @ 3400rpm |

All-alloy, ohv, 1983cc V-twin; 82bhp @ 5250rpm; 103lb ft @ 3250rpm |

| Transmission |

5spd manual, RWD |

6spd manual, RWD |

6spd manual / auto |

6spd manual, RWD |

5spd manual, RWD |

| Suspension |

Independent, by sliding pillars, coils (f); live axle, semi-elliptics (r); telescopics (f/r) |

Upper links, wishbones (f); double wishbones (r); coil-over dampers (f/r) |

Upper links, wishbones (f); double wishbones (r); coil-over dampers (f/r) |

Upper links, wishbones (f); wishbones (r); coils and telescopics (f/r) |

Wishbones (f); swing arm (r); coil-overs (f/r) |

| Steering |

Rack and pinion |

Powered rack and pinion |

Powered rack and pinion |

Powered rack |

Rack |

| Brakes |

Discs/drums |

Ventilated discs |

Ventilated discs |

Discs |

Discs |

| Top speed |

124mph |

160mph |

170mph |

155mph |

115mph |

| Price new |

£12,999 (1984) |

£62,000 |

£110,000 |

£85,200 |

£31,000 |

| Price now |

£30-50,000 |

from £50,000 |

£180,000 |

£70k+ |

from £25,000 |

READ MORE

Morgan reveals limited-edition 50th anniversary Plus 8

Supersonic! Behind the wheel of the LCC Rocket

Is this the most beautiful classic car you’ve never heard of?

Malcolm Thorne

Malcolm Thorne is a contributor to – and former Deputy Editor of – Classic & Sports Car