Despite those challenges, the extra muscle is immediately apparent, with an easy 55-60mph on the straights accompanied, as you might expect, by a more robust soundtrack.

In similar road conditions, Keith’s blown Minor MM feels good for at least an extra 10mph over and above Ray’s standard-tune Alta car.

“The supercharger transforms things,” says Keith. “You get the benefits of the Alta head – more drivability – then the blower comes in at the top end.

“The combination of Alta head and supercharger gives lots of torque through the gears, and acceleration that keeps up with modern traffic and holds speed up hills.”

‘The blown Morris Minor MM highlighted how full of zest a more modestly specified Alta-tuned Minor could be’

Notwithstanding the engine being as off-colour as the weather on the day of our photoshoot, the appeal of a blown Alta-head Minor MM not only shines through, but also highlights how competent, sweet-natured and full of zest the more modestly specified Alta-tuned Morris can be.

You can see why it was such a well-regarded conversion in its day.

But let’s square the circle.

Years ago, I was able to do a comparison road test of a Morris Eight Series E and a Wolseley Eight, two cars in effect identical but for their engines.

The Alta overhead-valve cylinder head was the ultimate add-on for the original Morris Minor MM

The overhead-valve Wolseley unit was peppily brisk, and I would say that its performance advantage and general character were very similar to what you experience with an Alta conversion.

Put another way, if it had got its act together, the team at the Nuffield Organization could have had a properly engined Morris Minor in production from the very beginning.

The Alta head conversion shows how good such a car could have been.

Images: John Bradshaw

Thanks to: Morris Minor Owners’ Club and Alta-head expert Graham Holt

Geoffrey Taylor and Alta cars

Geoffrey Taylor in his Alta at Brooklands © Getty

The Alta story starts in Kingston upon Thames, Surrey, in 1927, when Geoffrey Taylor, a young engineer working for the ABC car company, decided to build his own sports car from scratch.

By November 1928 the car was ready, right down to a homebuilt 1074cc all-aluminium twin-cam engine, all created in the stable block of the family home.

The car was named Alta, after a town in Alberta, Canada, which Taylor had come across in a novel.

Taylor subsequently set up the Alta Car and Engineering Company in January 1931, and between then and 1935 he built 12 Alta ‘1100’ sports cars.

He also devised his own Roots-type superchargers and developed an improved 1500cc version of his engine; from that came a run of six 1500cc racers and seven roadgoing sports cars.

The ultimate pre-war Altas followed: three supercharged racers with all-independent sliding-pillar suspension, the best capable of challenging the works 2-litre ERAs.

Government contract work and developing Ford’s V8 for marine use kept the Tolworth works busy, while a further earner was an Austin Seven aluminium cylinder head that showed the potential for bolt-on tuning gear for popular cars.

Approximately 2000 Morris Minor MMs were fitted with Alta cylinder heads

Post-war, Taylor built a run of 1.5-litre supercharged Grand Prix cars, and from these he developed an unsupercharged 2-litre car for Formula Two.

The unblown unit also powered the successful HWM racers and was used by Connaught, and it was this use of Alta engines that thrust the firm to prominence.

The 2.5-litre Alta unit powered the B-series Grand Prix Connaught, and this car, driven by Tony Brooks, took a historic GP win at Syracuse in 1955, marking the beginning of Britain’s establishment at the forefront of Formula One.

In 1956, after completing a last batch of 2.5-litre engines and dogged by ill-health, Taylor closed the Alta works.

By that time he had diversified into the overhead-valve Morris head, which was launched in 1954.

Few writers bother to mention this in their reviews of Alta history, despite estimated production of around 2000 heads.

Morris Minor: the flat-four engine that never was

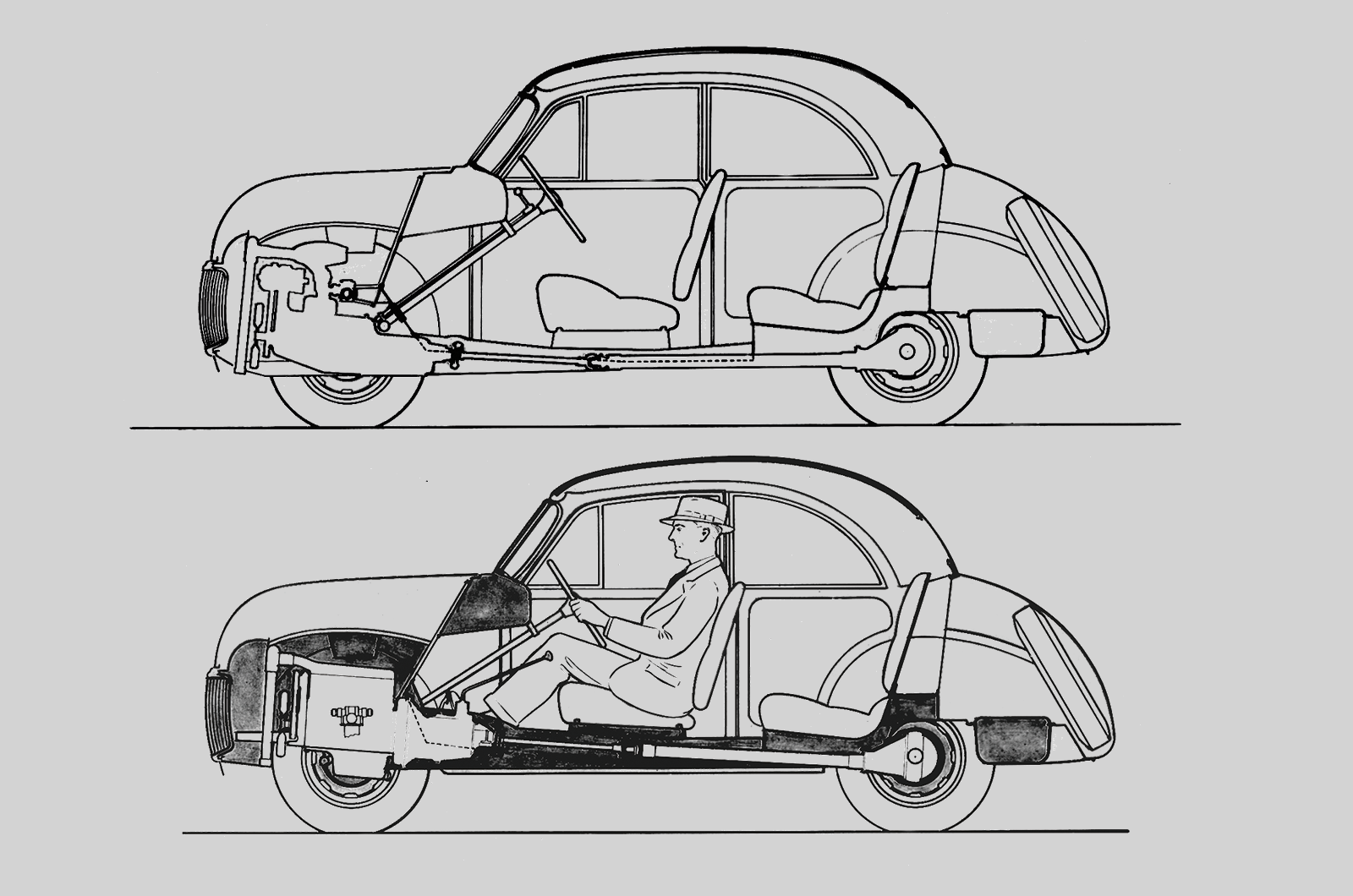

Morris Minor packaging drawings demonstrate the space-saving advantages of the flat-four (top) compared with a conventional in-line engine; a torque-tube and split propshaft were also proposed © BMIHT

The flat-four engine envisaged for the Minor was conceived in two capacities – 800cc and 1100cc – and was a cast-iron sidevalve unit.

But why a flat-four? A horizontally opposed engine is smoother and better-balanced than an in-line unit, but a more fundamental advantage is compactness.

Because the engine is shorter, the crankshaft and crankcase are more rigid, plus the engine isn’t as tall so the centre of gravity is lower.

Every bit as valuable is that a compact engine takes up less space in the vehicle, and for Minor creator Alec Issigonis few things mattered more.

The engine was indeed small – 13in from crank pulley to flywheel – and narrow, thanks to its old-fashioned sidevalve configuration, chosen by Issigonis for precisely that reason.

By September 1945, the original ’43 prototype had been fitted with the first experimental flat-four, which, evidence suggests, was of 800cc.

Subsequently an 1100cc unit arrived and was tried in another pre-production car.

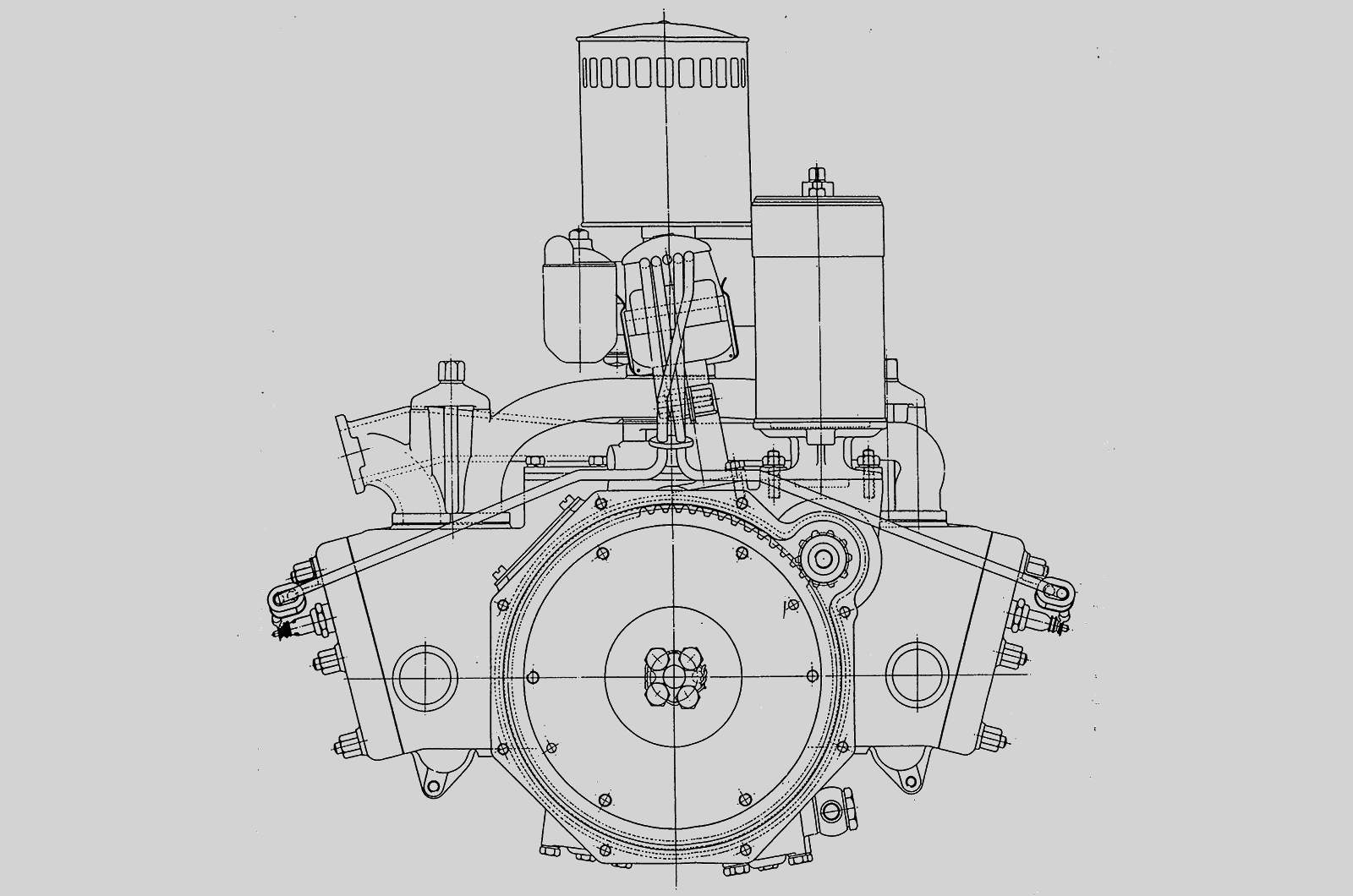

Surviving engineering drawings from 1946 depict two different versions of the 800cc engine, one called YF80M and the other ZF80M.

The ZF80M is a dry-sump design with a separate oil tank, one pump to distribute oil to the bearings and a second ‘scavenge’ pump to return it to the tank.

This expensive solution makes the engine less tall, for a still lower centre of gravity.

It appears that at least one dry-sump flat-four was tested in the ‘Mosquito’ prototype, but it’s hard to imagine the Morris accountants being enthusiastic about such elaborate engineering.

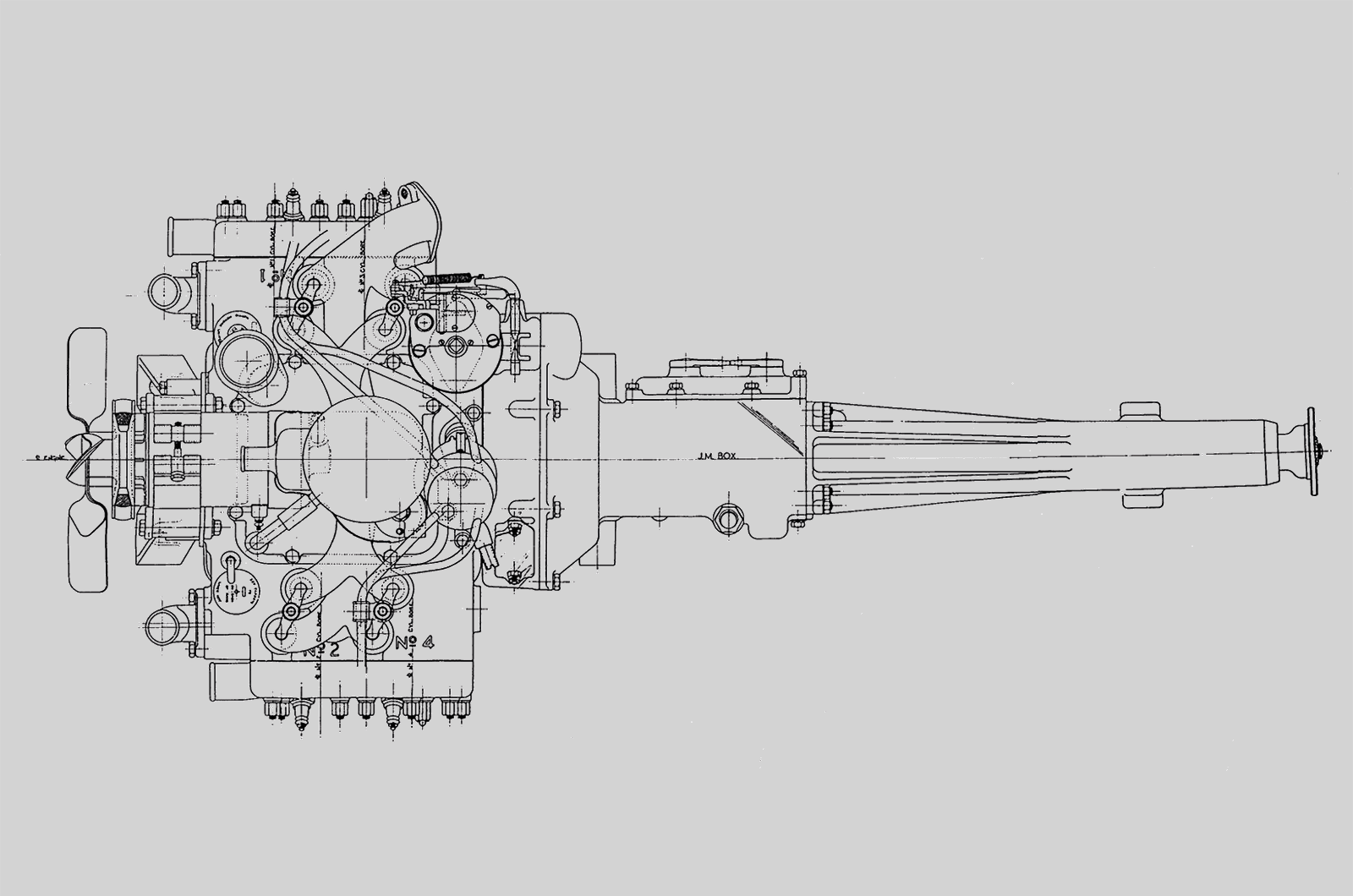

Vertical starter and downdraught SU carburettor for Morris’ YF80; the compact column-change gearbox is mated to a long tailshaft and short one-piece propshaft © BMIHT

YF80M is a more orthodox wet-sump design. As with the dry-sump engine, it had two main bearings.

With the shorter crank of a flat-four this isn’t necessarily a disadvantage if the mains are sufficiently beefy – and to add a centre bearing would increase the engine’s length.

According to Jack Daniels, right-hand man to Issigonis, the crank had generously proportioned main bearings and never gave any problems.

The engines acquitted themselves well, according to Daniels.

“We tested mainly the 1100, and that gave reasonable performance – much better than the Morris Eight engine,” he said.

“It was pretty good. You were conscious of a flat-four exhaust beat – a bit off-key and different from any other engine – but you got used to it.”

Former Morris Engines employee Fred Collis remembered his father driving a prototype with the flat-four from Coventry to Cowley.

“He said the car was marvellous and had far more speed than a Morris Eight,” he recalled. “He was very impressed by the performance.”

One-time Nuffield engineer Jim Lambert’s recollection was less rosy, but he was in his early 20s then and all he knew about the flat-four was secondhand.

“I don’t think it had a chance,” he said. “It was gutless and wasn’t any real advance on what we had. It wasn’t a big step forward.”

The experimental engines did have vibration problems, apparently caused by a poorly located flywheel.

Former Morris Engines employee John Barker recalled other failings: “Engineers in the experimental department said it died a death because of bearing trouble – the bearings were too noisy.

“I was told there was crankshaft whip, I believe because with only two main bearings there wasn’t enough support for the crank.”

Any tendency for the crankshaft to whip in extreme circumstances would have been exacerbated by vibrations from an out-of-true or loose flywheel.

Such development problems would normally be ironed out quickly, had time, resources and management goodwill allowed.

Morris’ ZF80M engine, with two oil pumps and no conventional oil pan; angled heads may not have been used; the pistons have recessed bowls © BMIHT

It wasn’t that simple, though. The flat-four was going to be expensive to produce.

In July 1947 it was calculated that the YF80M and its four-speed column-change gearbox would have cost just over £47 to manufacture; the Morris Eight engine and gearbox was costed at £38, making the boxer unit a whacking 24% costlier.

Worse, from Morris Engines’ perspective, it ‘wasn’t invented here’.

The division was struggling to put a family of in-line engines into production, including the 1000cc and 1100cc ‘fours’ it saw being used in the Mosquito and any spin-offs.

It can only have seen Issigonis’s flat-four as a cuckoo in an overcrowded nest. Development of the flat-four dragged on too long.

In June 1946 it was expected the engine would be in production before mid-’47, yet in April that year there were still concerns about the vibration problem, while the bigger unit for the Oxford still hadn’t made it off the drawing board.

More fundamentally, the Nuffield Organization’s management and Lord Nuffield himself weren’t even sure about bringing the Mosquito to production; its radical design evidently frightened them.

In a maelstrom of decisions and counter-decisions, consideration was given to cancelling the car in favour of an updated Morris Eight Series E, or at best making it in small numbers with an MG badge.

The thought of an all-new flat-four must have had tired managers reaching for the smelling salts. The final blow came in June 1947 at a Morris board meeting.

Citing the arrival of a flat rate of road tax in place of the RAC horsepower system, the flat-four engine programme was abandoned; in October, the Mosquito was at last given the green light and pushed towards an end-of-1948 introduction, ultimately with a conventional in-line sidevalve engine.

Logic, fed by internal pressure from Morris Engines, had prevailed.

Enjoy more of the world’s best classic car content every month when you subscribe to C&SC – get our latest deals here

READ MORE

Why the Morris Minor Million is lilac

Buyer’s guide: Morris Minor MM & Series II

Is a Morris Eight the perfect starter classic?

Jon Pressnell

Jon Pressnell is a contributor to Classic & Sports Car