Late in the 1990s, American Ferrari collector Anthony Wang acquired the T59 but was never happy driving pre-war cars, so he rarely took it out of his stunning Long Island collection.

Then, early this year, the Bugatti rumour mill reported that ‘57248’ had at last returned to Europe.

The car is now with respected Bugatti specialist Tim Dutton, again being carefully fettled in preparation for fitting use.

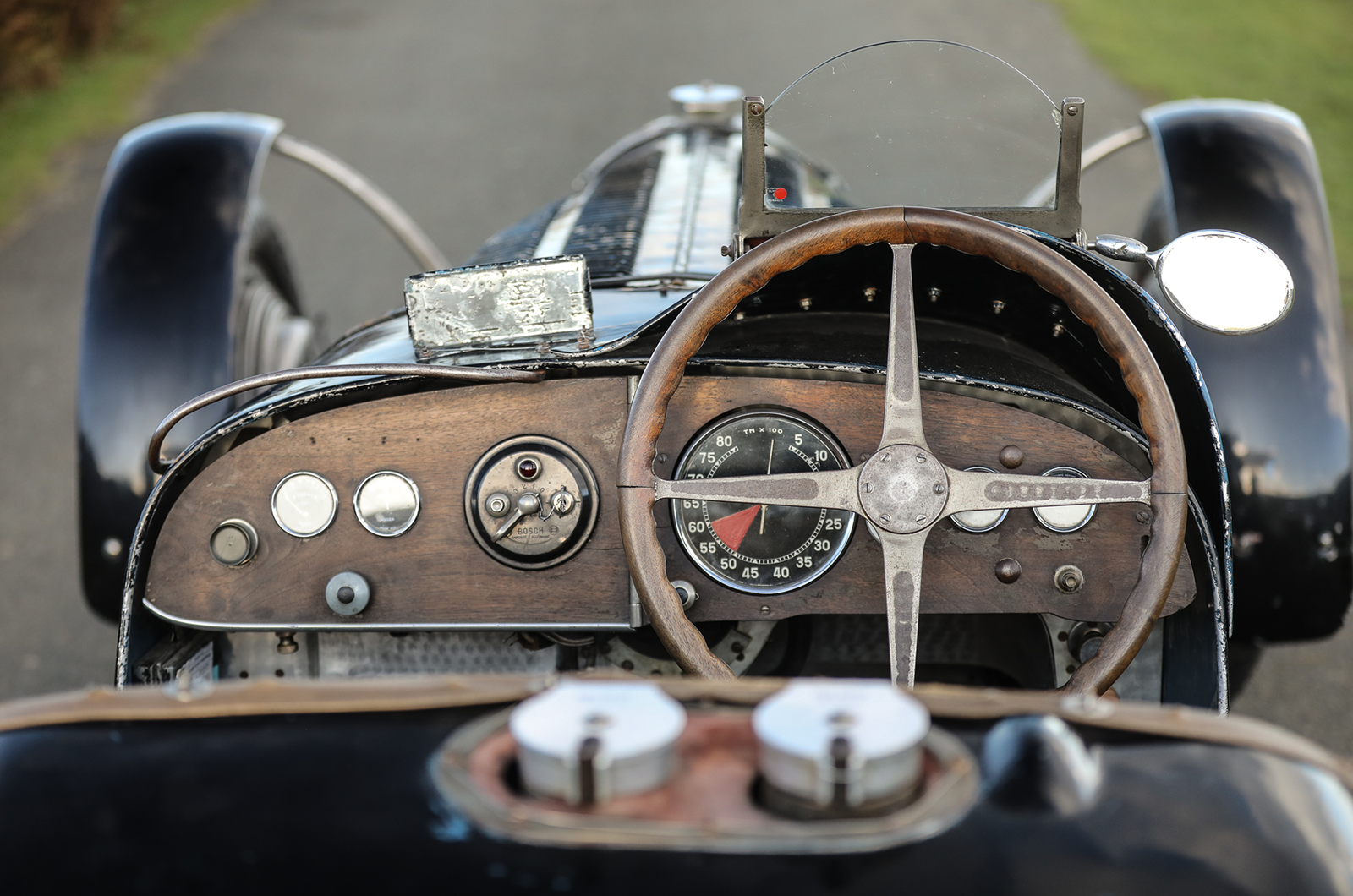

The highly original body is apart and the chassis stripped but, prior to its overhaul, Dutton trailered this timewarp legend to the LAT studio for an eagerly awaited photo session.

While dramatic lighting enhanced its prized originality, Dutton offered a fascinating insight into the design of the last great Bugatti Grand Prix car.

This ex-King Leopold Bugatti could sell for more than £10m at auction in September

“For me the glory years were the Type 35 and 51 when Molsheim had the funds to develop fresh ideas,” he said.

“Finances were really stretched by 1933 and the main focus was on road cars. Also Jean Bugatti was a better body designer than he was an engineer. Ettore was then less interested in Grand Prix racing – possibly disillusioned at the quantum leap in design from Mercedes and Auto Union thanks to state backing.”

For Dutton, the Type 59’s design was dated even before it was built: “Bugatti insisted on sticking with a live axle, which is less important when running on smooth modern tracks but on the bumpy road circuits it was very limited.

For Dutton, the Type 59’s design was dated even before it was built: “Bugatti insisted on sticking with a live axle, which is less important when running on smooth modern tracks but on the bumpy road circuits it was very limited.

“The chassis has all the good points of the Type 35 with a stiff front and softer rear. Its strength is in all the right places. The solid-mounted engine further stiffened the chassis, which all helped to make the suspension work. I don’t think Bugatti understood roll centres, so solid was the only way.”

It’s easy to see why there has been a run of replica Type 59s because the engine is basically a development of the Type 57: “The block is the same, but with a dry sump, no camshaft damper and different cam profiles.

“For the longer sports car races, the firing order was changed to smooth out the running. The sports car gearbox was an early crash design developed from the Type 55. It’s a lovely strong unit with a good change.”

Is there a more original competition Bugatti?

One of the problems with early Type 59s was rear-wheel steering that used to distort the leaf springs under power.

“Thankfully the later cars had radius arms,” says Dutton. “The split front axle was another attempt to cope with the disadvantages of the outdated live axle. With a live front axle, the wheels will grab, twist and shimmer under braking, particularly on rough tracks, so the split helps to compensate for tramp. The double-reduction back axle was a way to get the weight down lower but it was a headache.”

Some non-Bugatti restorers criticise the complex de Ram dampers, but not Dutton: “They must have cost a fortune and it takes a dedicated specialist to set them up. But again you have to consider the poor state of road circuits in the ’30s.”

The Type 59’s distinctive combined hub and brake drum design may look over-complex compared to a standard wire, “but they were a lot simpler to make, were lighter, and just as strong. With its dog drive, the straight wires are just lateral support for the rim. Best of all, there’s no torsional load on the hub or the brake. It’s classic Ettore. He always wanted to be different”.

Spacious cabin – but watch your elbows

“If the Type 59 had appeared in 1929 it would have been an amazing car,” concludes Dutton, “but by 1932 Bugatti really needed a new concept. If you put doughnut wheels on a Type 59 today, it should beat an ERA – but that would be sacrilegious with those beautiful wires.”

Wider and lower than the T51 it replaced, it’s little wonder that the Type 59 transformed into the ultimate Bugatti sports car.

Wouldn’t it be fascinating to restage The Autocar’s 1938 Fastest Sports Car contest to prove it. Any Alfa, Talbot or Delahaye owners up for the challenge?

FACTFILE

Bugatti Type 59

- Produced/number built 1933-’36/six

- Construction beam chassis, magnesium body

- Engine front-mounted, iron block and head with alloy crankcase dual-overhead-camshaft 3257cc straight-eight, with two valves per cylinder, six plain bearings, Roots supercharger, two Zenith 52mm carburettors and Scintilla Vertex magneto

- Max power 250bhp @ 5000rpm

- Transmission separate central four-speed gearbox, driving rear wheels

- Suspension: front live axle with semi-elliptic leaf springs and de Ram shock absorbers rear reversed quarter-elliptic leaf springs, radius arms and de Ram shock absorbers

- Steering worm and wheel

- Brakes cable-operated drums

- Track 4ft 1 in (1251mm)

- Wheelbase 8ft 6 in (2597mm)

- Weight 1650lb (748kg)

- Wheels piano-wire style with 6x19in tyres

- 0-60mph 6 secs

- Top speed 160mph

Images: Peter Spinney/Mathieu Heurtault for Gooding & Company

READ MORE

Concours of Elegance to host Gooding’s first European sale

Get closer to the Concours of Elegance with C&SC – and you could be a winner!

The 20 most expensive cars sold at the Paris auctions 2020

Mick Walsh

Mick Walsh is Classic & Sports Car’s International Editor

Early in May, the Grand-Mère was shipped out to Tunisia for a three-heat sports car GP event.

Early in May, the Grand-Mère was shipped out to Tunisia for a three-heat sports car GP event.

For Dutton, the Type 59’s design was dated even before it was built: “Bugatti insisted on sticking with a live axle, which is less important when running on smooth modern tracks but on the bumpy road circuits it was very limited.

For Dutton, the Type 59’s design was dated even before it was built: “Bugatti insisted on sticking with a live axle, which is less important when running on smooth modern tracks but on the bumpy road circuits it was very limited.