“The presumption was that the Renault was the best back then,” Damon recalls. “But that Ford [V8 of 1994] was surprisingly good, although probably not as powerful.

“It used a manual gearbox and Michael did some strange downshifting: he kept his foot slightly open rather than blip it.

“I think he was blowing the diffuser, blasting it with exhaust gas. We couldn’t do that because we had a semi-auto.”

Ah, but was Hill cheesed off when his rival’s Benetton received Renault power for 1995? “Not half!” he replies.

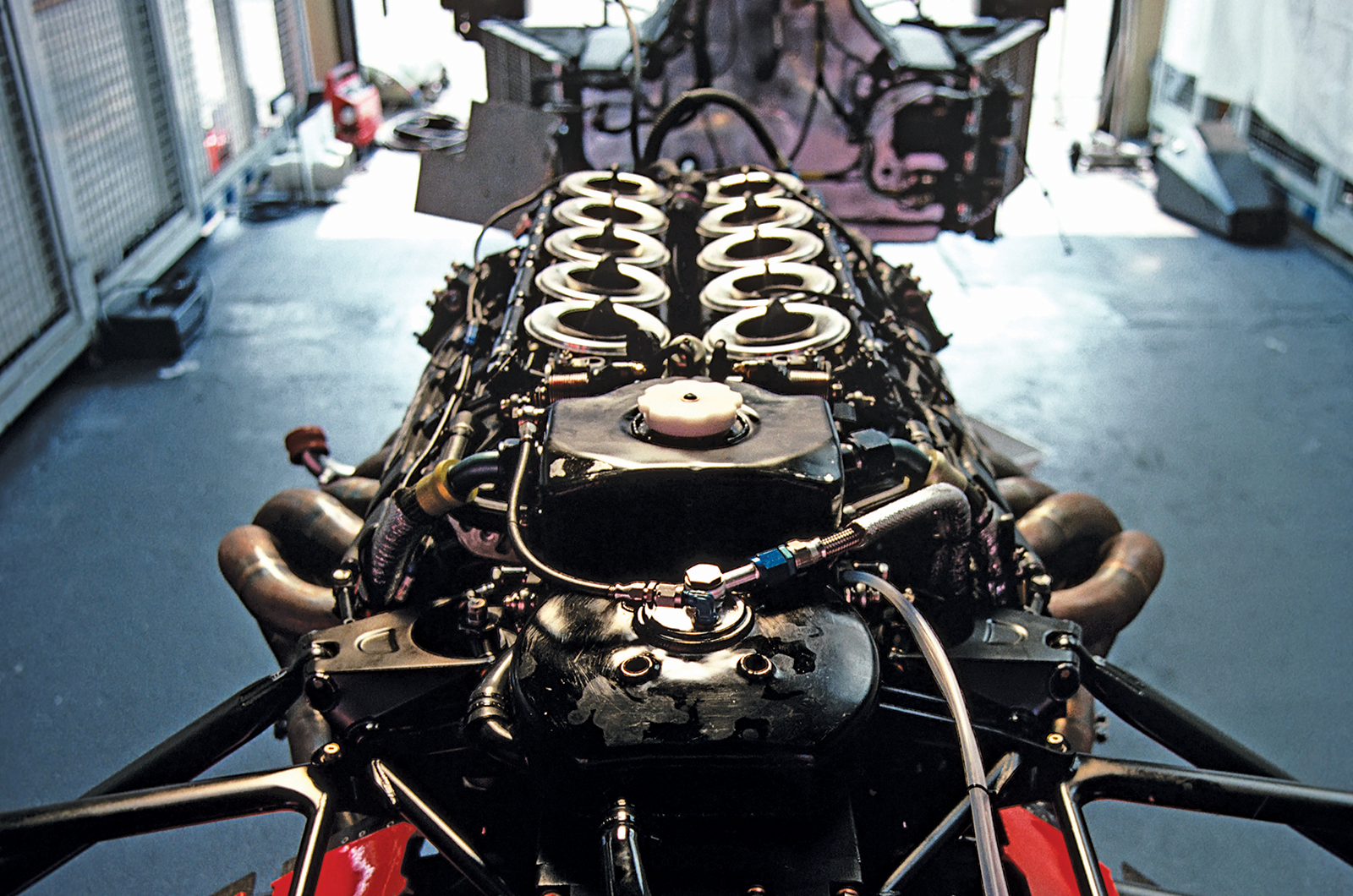

Ferrari’s first V10 – by Osamu Goto for 1996 – was a 75º. Honda returned in 2000 with an 88º, which became a 94º in 2004. By 2005, all bar one had followed Ferrari’s by-then 90º lead.

BMW, bidding to catch up, broke the 19,000rpm barrier in 2002, as increasingly sophisticated software juggled ignition and injection on the brink of disaster.

Yet it was the drivability and reliability of the more established Ferrari that held sway until the V10s’ final year, when Renault’s 72º appeared with the greater stiffness – within the engine itself and between it and the chassis – required by a design preference for a rearward weight bias.

The 2.4-litre V8s that replaced the V10s in 2006 were much more proscribed: fixed vee angles (90º) and cylinder spacings, plus minimums for weight (95kg), bore (98mm), crankshaft centre-line height and overall CoG.

There were bans on variable inlets, reciprocating poppet-valves were made mandatory and fewer permitted materials were more tightly defined.

Renault’s 2001 comeback was with a 111º, hopeful of giant leaps in centre of gravity and aero advantage – but it tripped badly. For some, this slippery slope had begun long ago.

“Turbos were more challenging,” says Osamu. “More possibilities: fuel-consumption restrictions; different boosts, air/fuel mixtures and ignition timings; and less electronic assistance.

“It was very easy to break an engine. Naturally aspirated was more simple: optimising various minor tunings, and every year a 3% rise in revs and power.”

That’s easy for him to say.

Images: Getty

Enjoy more of the world’s best classic car content every month when you subscribe to C&SC – get our latest deals here

READ MORE

Porsche Carrera GT vs Dodge Viper vs Lamborghini Gallardo: V10 titans

How Renault turbocharged F1

Future classic: Audi R8 V10 RWD