You are surrounded by walnut veneers, but the door cards and furniture are restrained in design.

A modest instrument display is dominated by a 110mph speedometer and flanked by much smaller gauges for amps, fuel/oil pressure and water temperature.

A winder controls the glass division

Less familiar are the six chrome pull-out knobs for map and instrument lighting, and an independent switch for a reversing light.

A small lever marked ‘start’ and ‘run’ amounts to a choke, but it feels undignified to call it that.

A three-position switch offers the option of running on the left- or right-hand fuel pump, or both, and the left/right toggle in the centre of the dash operates trafficators that pop out of the centre pillars and which go largely unnoticed by modern motorists.

Twin horns mounted under the headlights have ‘high’ and ‘low’ settings.

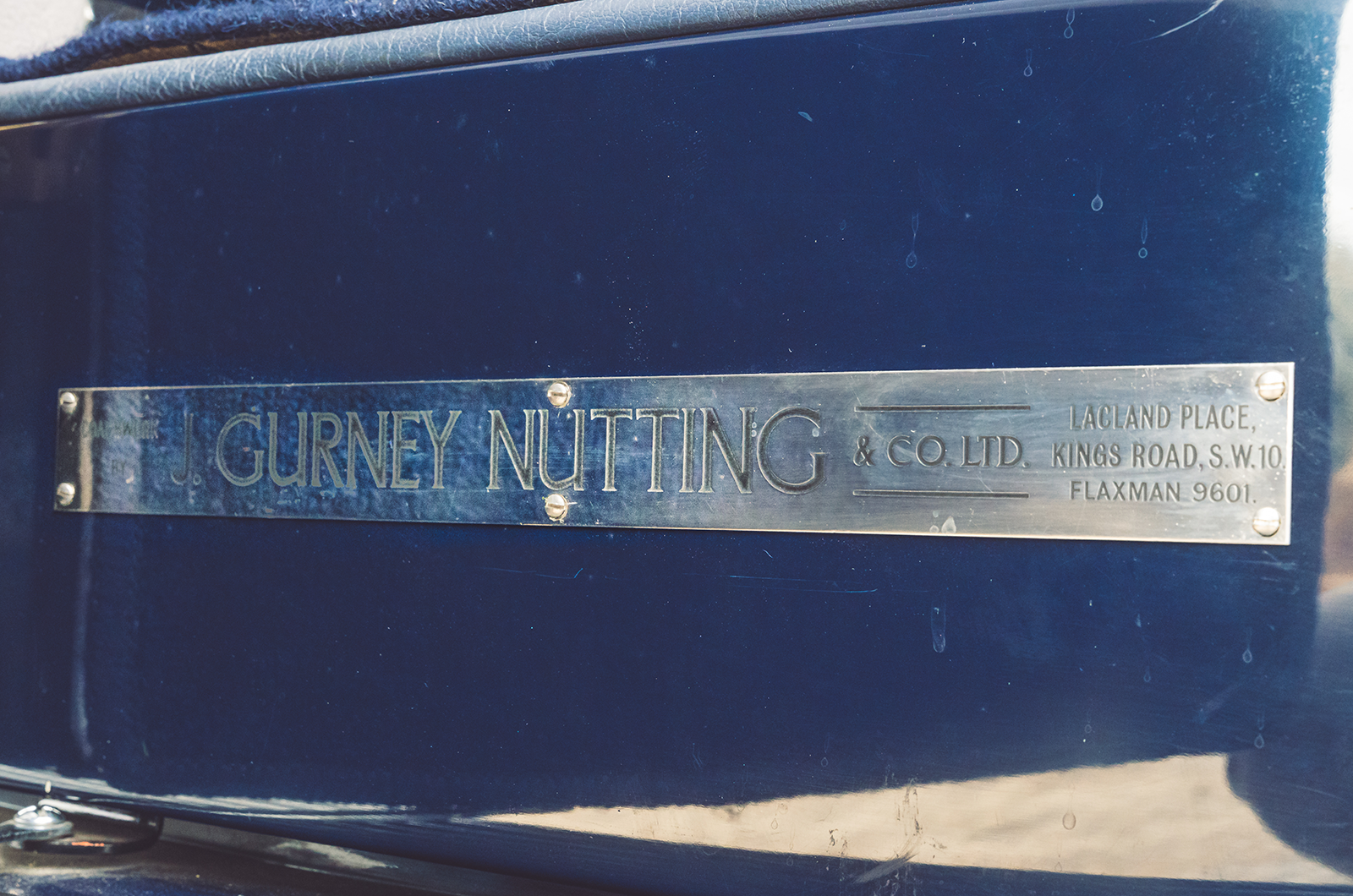

This elegant Rolls-Royce Phantom III was sent to Gurney Nutting in June 1937

The idea of a touring limousine was that owners could use their driver for formal duties – enjoying the rear compartment as a private space behind the wind-up glass division – or put the Phantom to use as a more ‘social’ conveyance and drive themselves.

With the division wound out of sight, it becomes a grand but reasonably intimate saloon, in which the front-seat accommodation is not entirely subordinate to the back-seat lounging room.

Rear occupants relax on soft, warm West of England cloth, feet supported on twin rests and privacy assured by deep C-pillars with uplit Art Deco companion mirrors built-in.

Some Phantom IIIs had electric windows and even powered rear blinds, but the only toys on this example are a radio built into the division and twin writing desks.

‘The Phantom III’s mission was to be a lighter, faster, more refined and easier-to-handle car than the outgoing Phantom II’

Those original owners who left the driving to the hired help missed out on something special: a car as effortless to drive as the technology of 80-odd years ago could make it.

You sit ‘on’ rather than ‘in’ the Phantom III, impressed by its smooth, relatively high-geared steering (three turns from lock to lock) and the way the massive sidewalls of the 18in tyres fail to acknowledge most of the realities of the road surface below.

The acceleration is fluent and majestic, a seamless waft of luxurious aspiration that motors you forward on a silky thread.

The Phantom’s natural brisk trot means that you never hold up modern traffic but keep station with it.

An Art Deco C-pillar mirror adds to the opulence in the cabin

It is far from agile – the swift accumulation of understeer when you first try to pour three tons into a meaningful turn with a good sight line hastily curbs your B-road ambitions – but neither does the Phantom III roll all that much for something quite so tall and so heavy.

That the workings of the potent, well-balanced brakes – massive drums boosted by the usual gearbox-driven servo – hardly crossed my mind is remarkable in a car approaching its 90th birthday.

The silent, handily placed gearchange has a buttery feel as it clicks home in its four-fingered gate.

The fold-out writing desks enhance the cabin’s office appeal

It is engineered to feed back the sort of well-damped delicacy of movement that permeates all the Phantom’s controls, yet they do so with a sense of robustness that tells you nothing is going to break.

First gear seems largely redundant and third is optional; you could probably have out-accelerated almost anything encountered on pre-war roads just using second and top.

This was the sort of flexibility buyers demanded in a time before automatic transmissions.

The Rolls-Royce Phantom III understeers, but body roll is well contained

It is a telling commentary on the Phantom III that the survival rate is 90%, although the huge cost of rebuilding the engine (a £1500 invoice even in the mid-’60s) has always made enthusiasts understandably cautious of the model’s complexity.

At five years in the making, even the parents of this magnificent statement of engineering prowess seemed to question the wisdom of its conception.

Mindful of the famous three-year Rolls-Royce guarantee, they were perhaps quietly relieved when WW2 brought chassis production to an end, although they were still being bodied in 1941 and the last car was not sold until 1947.

A kneeling Spirit of Ecstasy sits atop the radiator

This Phantom III has found a new home and will hopefully see some regular use; not using a Phantom III is probably the most expensive way of owning one, with so many complex systems requiring regular exercise.

The Best Car in the World? If you had the money to buy it – and the resources to maintain it – and needed a car in which to travel long distances as quietly, roomily and speedily as the prevailing technology allowed some 80 years ago, then I can’t think of anything better.

Images: Max Edleston

Thanks to: P&A Wood

Factfile

Rolls-Royce Phantom III

- Sold/number built 1936-’39/710

- Construction steel box-section chassis, custom bodywork

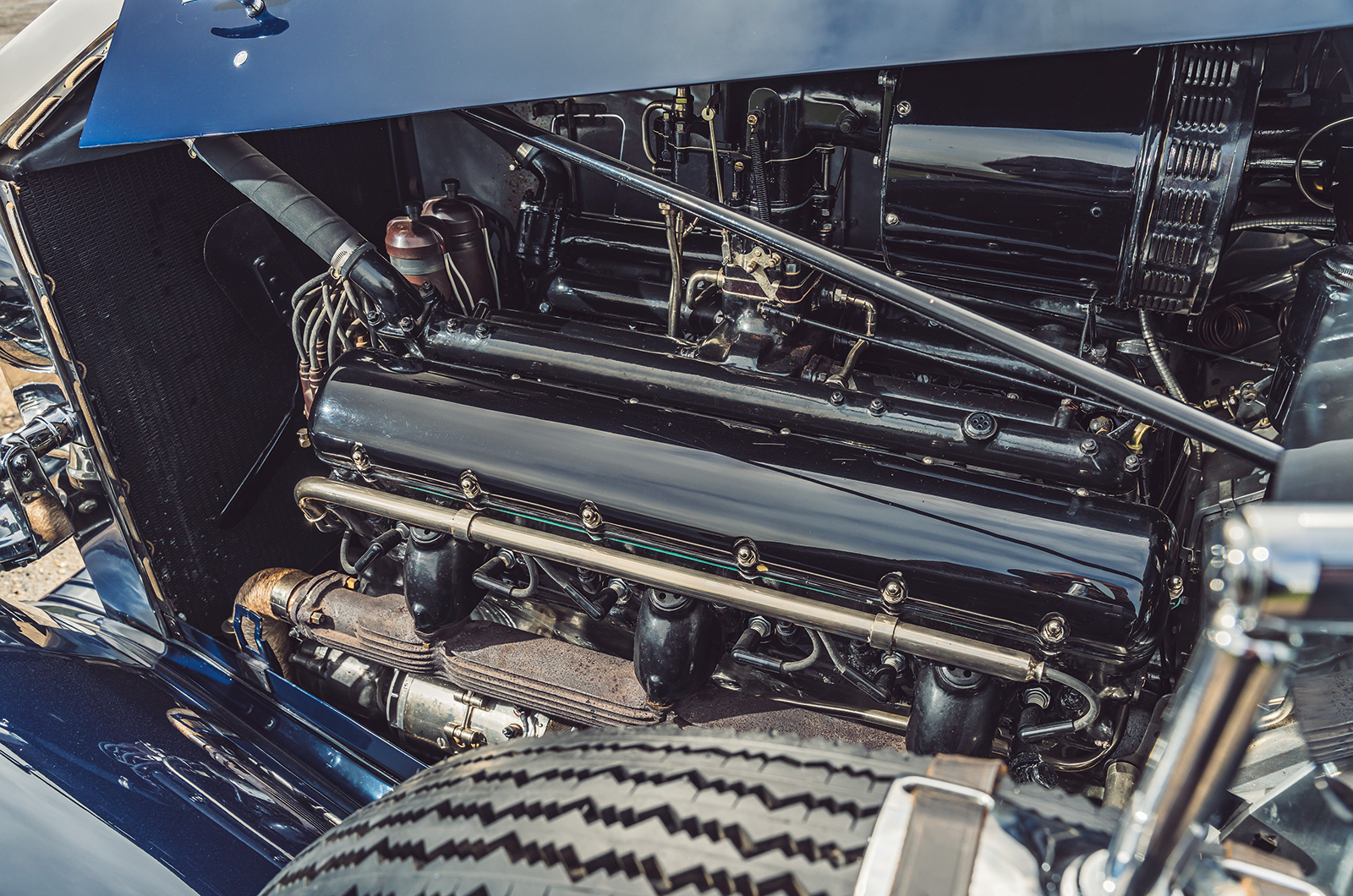

- Engine all-alloy, ohv, 7338cc V12, single twin-choke Stromberg carburettor

- Max power 165-180bhp @ 3500rpm

- Max torque n/a

- Transmission four-speed manual, RWD

- Suspension: front independent, by wishbones, coil springs rear live axle, semi-elliptic leaf springs, anti-roll bar; hydraulic dampers f/r

- Steering worm and sector

- Brakes drums, with servo

- Length 17ft 7in (5359mm)

- Width 6ft 5in (1958mm)

- Height n/a

- Wheelbase 11ft 10in (3607mm)

- Weight 6100lb (2770kg)

- Mpg 8

- 0-60mph 16.8 secs

- Top speed 92mph

- Price new £2600

- Price now £85-200,000*

*Prices correct at date of original publication

Enjoy more of the world’s best classic car content every month when you subscribe to C&SC – get our latest deals here

READ MORE

25 of the most luxurious classic cars ever

Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow II vs Cadillac Seville vs Jaguar XJ12 LWB: game of thrones

Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud III vs Cadillac Series 62: the sky is the limit

Martin Buckley

Senior Contributor, Classic & Sports Car