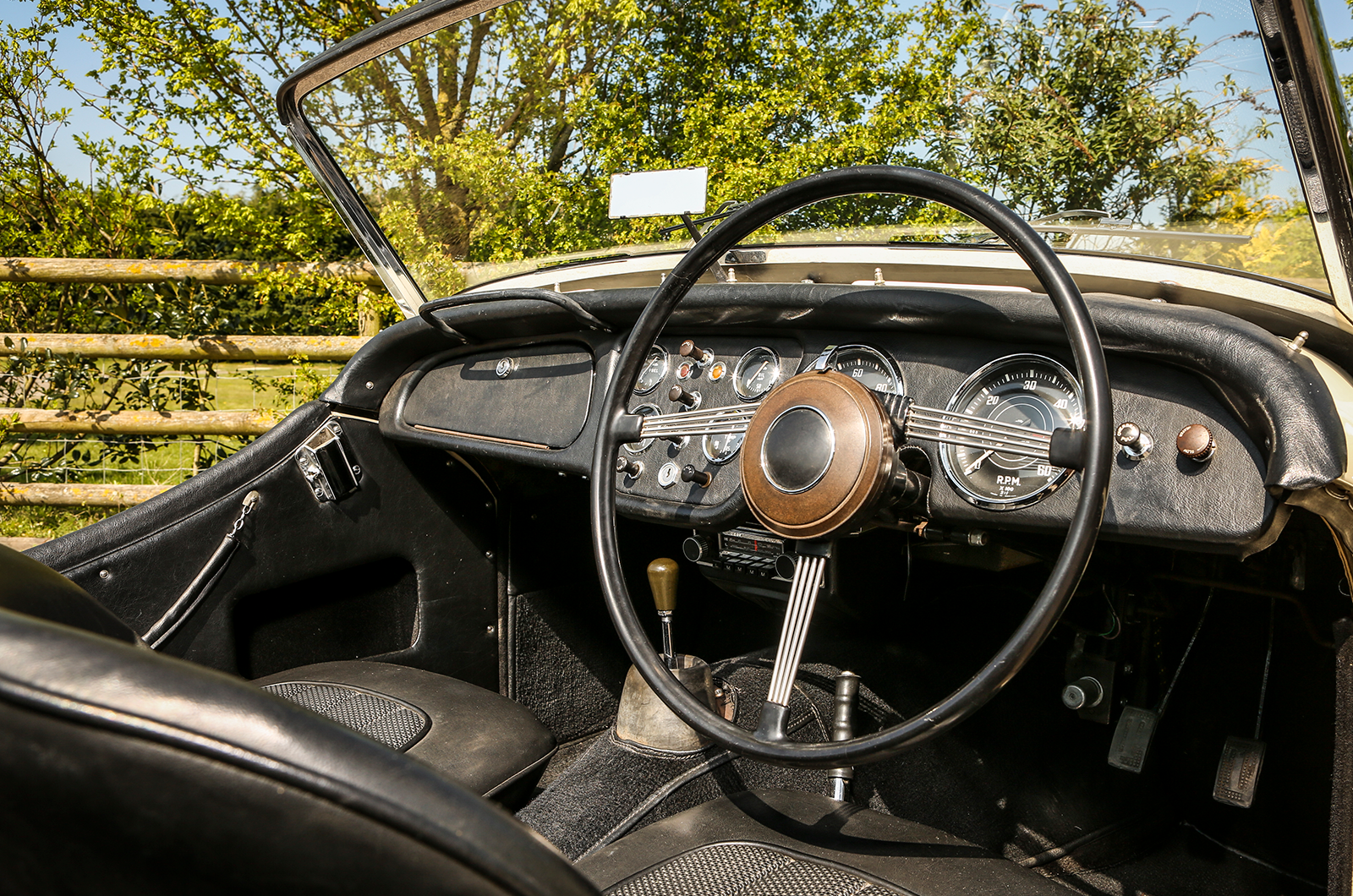

Squeeze yourself into the narrow cabin of the Triumph, in contrast, and you feel every inch the ’50s rally hero, battling the weather on the RAC or storming an Alpine col.

The simple, rugged design of the cockpit is purposeful rather than graceful, with cutaway doors and close-set wheel that feel very vintage, as do the thinly padded bucket seats.

You want to grab it by the scruff and hurl it up a mountain pass, or hunch down low as you blast along a route nationale, with that lovely sprung wheel shimmying like a drunken sailor as the car finds its own way down the road.

It’s not a precision tool, but it feels wonderfully evocative.

There’s a hint of Ferrari 166MM in the Swallow’s front end

As you spend longer with the two cars you come to appreciate their individual characters, and have time to ponder how different they feel, in spite of sharing so many parts.

Although both feature identical instruments and switchgear, the dashboard of the Doretti feels much classier and less workmanlike – even if the rev-counter is all but useless, being positioned over to the left well beyond the driver’s natural line of sight.

The impression of being in a sports tourer is heightened by the Swallow’s practical and easy to erect hood, which is a far cry from the Triumph’s draughty lift-the-dot tarpaulin on sticks.

The Doretti feels more modern to drive than the TR2

The Doretti’s effective weatherproofing does highlight the incongruous lack of proper windows, though, while any pretence at being a tourer is quashed the instant you open the boot.

It really is tiny, as are the footwells.

‘Our’ car has a modified TR2 gearbox cover, but the Walsall original was inexplicably wide.

The Swallow is a bigger car in every direction, but the additional bulk doesn’t translate into extra passenger space.

Just 276 Swallow Dorettis were produced

TR2 owners will rejoice in the lack of that car’s sidescreen mounts, because the evil chromed wedges are ideally positioned to kneecap the unsuspecting.

The Swallow’s handbrake is also more usefully placed on top of the transmission tunnel rather than rubbing up against your left shin.

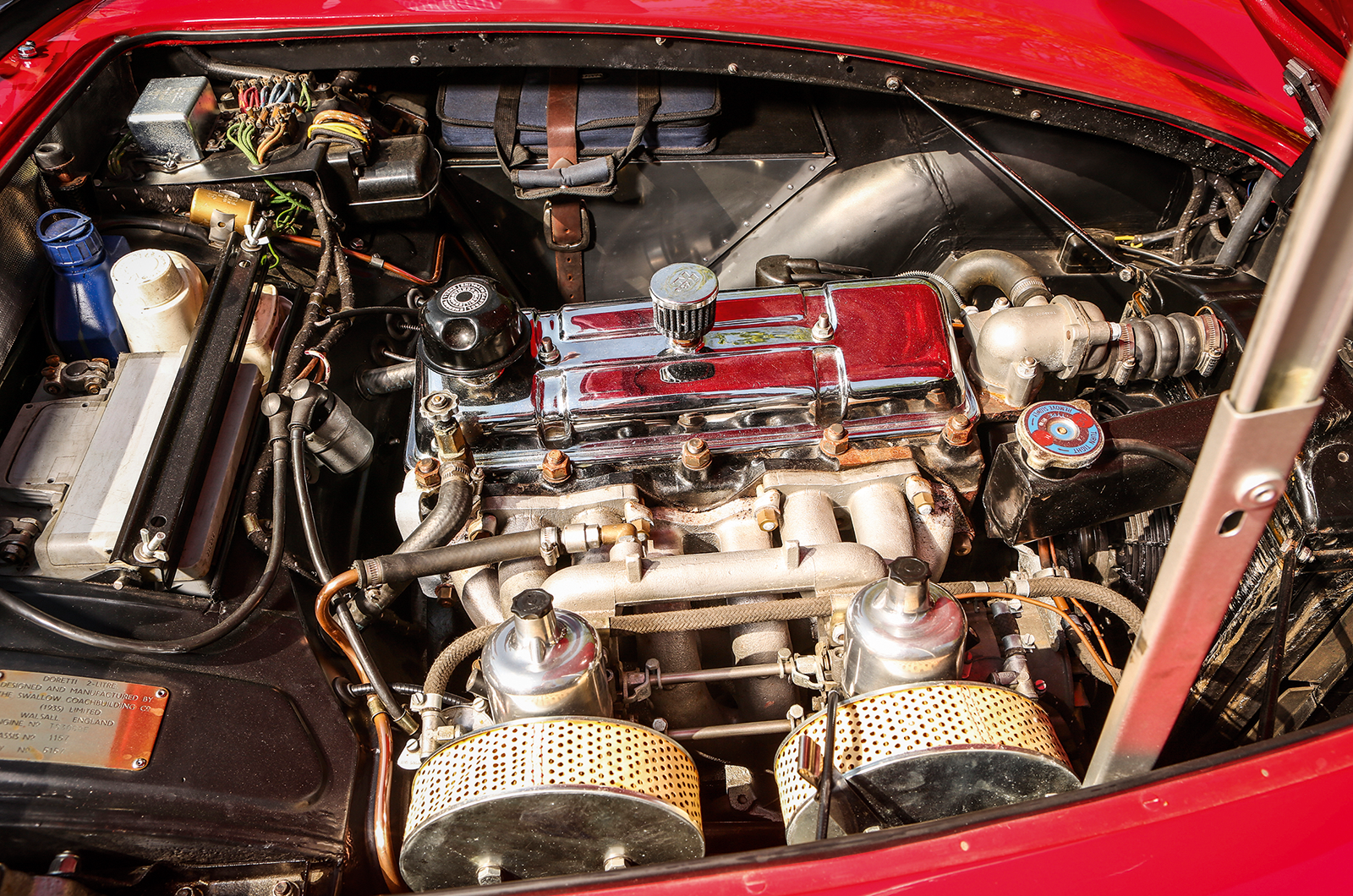

With a noticeably stiffer chassis, a longer wheelbase (the engine is mounted 7in further back in the frame) and radius arms at the rear, the Doretti does without the Triumph’s shake, rattle and roll.

A pair of unusual fins on the Swallow’s tail

The result was not only more civilised but, according to Don Truman, who, as well as being a TR2 owner, briefly raced a works Doretti in period, it was also a superior car in terms of usable performance. It was safer, too.

Sir John Black was a staunch supporter of the Swallow and keen to adopt it as a Triumph product.

As such, the first production car, finished in metallic silver with red interior trim to match his Bentley, was delivered to him in November ’53.

Keen to explore the car’s performance, Black had Richardson take him for a high-speed run in it, but the experiment ended abruptly when a lorry turned across their path.

Unusually, the tachometer is located on the far left of the Swallow’s dash

Black was seriously injured in the accident and was forced into retirement as a result, although he had the strength of the Doretti to thank for his survival.

A few miles behind the wheel of the Doretti is enough to confirm that it is a good design, and that it was full of potential. So what went wrong?

Alas, it was just a bit too good.

Tube Investments’ primary business was as a components supplier, and when it became clear that the Doretti was capable of stealing its rivals’ thunder the manufacturers, among them Jaguar, began to grumble.

In an alternate reality, the planned MkII Swallow Doretti might have replaced the Triumph TR2

Drop the Doretti, or we’ll take our business elsewhere, was the message.

Given that the car was little more than an indulgence for TI, it’s not surprising that it was quietly withdrawn from production in February ’55 after only 276 had been built.

Ironically, Rainbow was just readying an improved MkII version.

It’s easy to speculate, but had Sir John still been running Standard-Triumph by then, perhaps the Swallow might have been considered as the TR2’s replacement.

It’s difficult to escape the Triumph’s old-school appeal

Which is the better car? Objectively, it has to be the Doretti.

It feels more modern, more accomplished and has far more elegant styling.

Alongside the Swallow, the TR2 looks and feels like a dated lash-up, a decade or so older.

Yet sports cars are an emotive subject and it’s rarely possible to be objective.

Driving the Triumph TR2 and the Swallow Doretti back to back reveals their differences

It may lack the Doretti’s added level of sophistication, but the Triumph is a car that I have long coveted and, of the two, irrational though it may be, the masochist within can’t get enough of its vintage charm.

The Swallow’s life may have been unfairly cut short, but the Triumph’s success was fully justified.

Images: Tony Baker

Thanks to: Phil Collins; Nigel Wilcox; the TR Register

This was originally in our July 2015 magazine; all information was correct at the date of first publication

Dorothy Deen

The Doretti name was bought from Dorothy Deen for $1

One name that is inextricably linked to the Swallow Doretti is that of Dorothy Deen.

She was the driving force behind both the Swallow and the TR2 in the western half of the United States. Her company – Cal Sales Inc – marketed both cars there.

Before moving into the import business, Deen had been involved with another company – Cal Specialties – which had sold a range of accessories under the Doretti brand, a go-faster Italianised version of her name.

When the Swallow project got under way, the British firm bought the trademark for $1.

An enigmatic figure in the male-dominated 1950s American motor industry, there were rumours in the US that she had designed the car herself, but there was no truth to them.

Competitive edge

Of the two cars, the Triumph garnered the more impressive competition record.

Its first major success came on the 1954 RAC Rally, when TR2s finished first and second, as well as clinching the ladies’ prize.

The Triumph gained an enviable reputation in rallying, but also did well at Le Mans: a near-standard car came a creditable 15th in ’54, averaging 75mph and an astonishing 34mpg.

In the same year, another mostly stock TR2 took 27th place out of a field of about 500 cars on the gruelling Mille Miglia, while a works entry in the ’54 Tourist Trophy landed the team prize for Triumph.

On this side of the Atlantic, the Doretti was largely absent from racing – an exception being at the car’s UK launch in July ’54 where eight journalists took to the track at Silverstone.

Competition was actively encouraged in the US, with tuning kits widely available.

For owners craving a serious power boost, Max Balchowsky built a handful of V8 monsters boasting 300bhp.

Four had Buick motors, one was Cadillac-powered and the other sported a Chevy lump.

Factfiles

Triumph TR2

- Sold/number built 1953-’55/8628

- Construction steel cruciform chassis, pressed-steel body with bolt-on panels

- Engine all-iron, ohv 1991cc ‘four’, twin SU carburettors

- Max power 90bhp @ 4800rpm

- Max torque 117lb ft @ 3000rpm

- Transmission four-speed manual with optional overdrive, RWD

- Suspension: front double wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers rear semi-elliptic leaf springs, lever-arm dampers

- Steering Bishop cam and lever

- Brakes drums

- Length 12ft 7in (3840mm)

- Width 4ft 7½in (1410mm)

- Height 4ft 2in (1270mm)

- Wheelbase 7ft 4in (2240mm)

- Weight 2100lb (953kg)

- 0-60mph 11.9 secs

- Top speed 105mph

- Mpg 32

- Price new £886

Swallow Doretti

- Sold/number built 1954-’55/276

- Construction tubular steel chassis, steel body with aluminium panels

- Engine all-iron, ohv 1991cc ‘four’, twin SU carburettors

- Max power 90bhp @ 4800rpm

- Max torque 117lb ft @ 3000rpm

- Transmission four-speed manual with optional overdrive, RWD

- Suspension: front double wishbones, coil springs, telescopics rear semi-elliptic leaf springs, top radius arms, lever-arms

- Steering Bishop cam and lever

- Brakes drums

- Length 13ft (3962mm)

- Width 4ft 4½in (1334mm)

- Height 5ft 1in (1549mm)

- Wheelbase 7ft 11in (2413mm)

- Weight 2156lb (978kg)

- 0-60mph 12.8 secs

- Top speed 101mph

- Mpg 30

- Price new £1107

Enjoy more of the world’s best classic car content every month when you subscribe to C&SC – get our latest deals here

READ MORE

The greatest ’50s sports cars: XK120 vs MGA, AC Ace, Healey 100 & TR3A

Shared heart: MG Midget 1500 vs Triumph Spitfire 1500

Buyer’s guide: Triumph Spitfire

Malcolm Thorne

Malcolm Thorne is a contributor to – and former Deputy Editor of – Classic & Sports Car