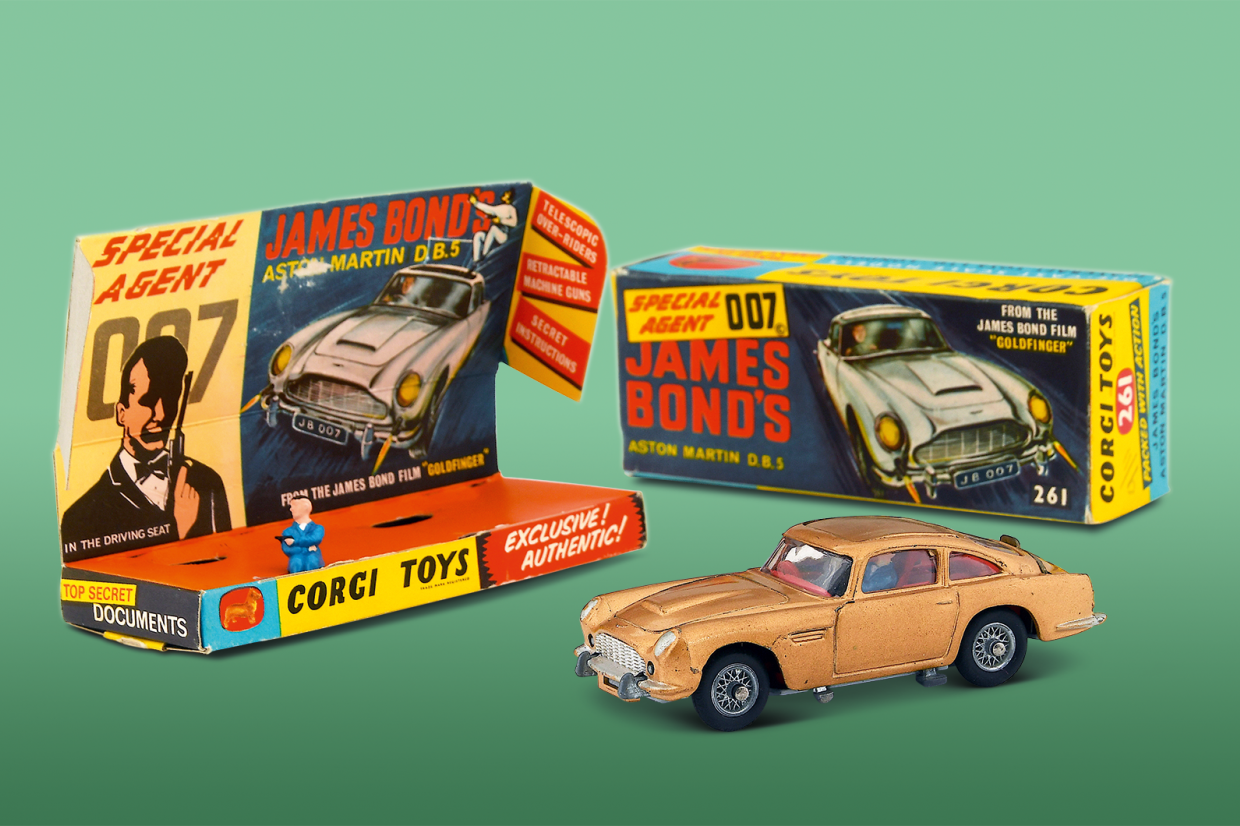

In October 1965, a 4in-long model car became the very first Christmas blockbuster toy, causing retail frenzy among parents desperate to get hold of one.

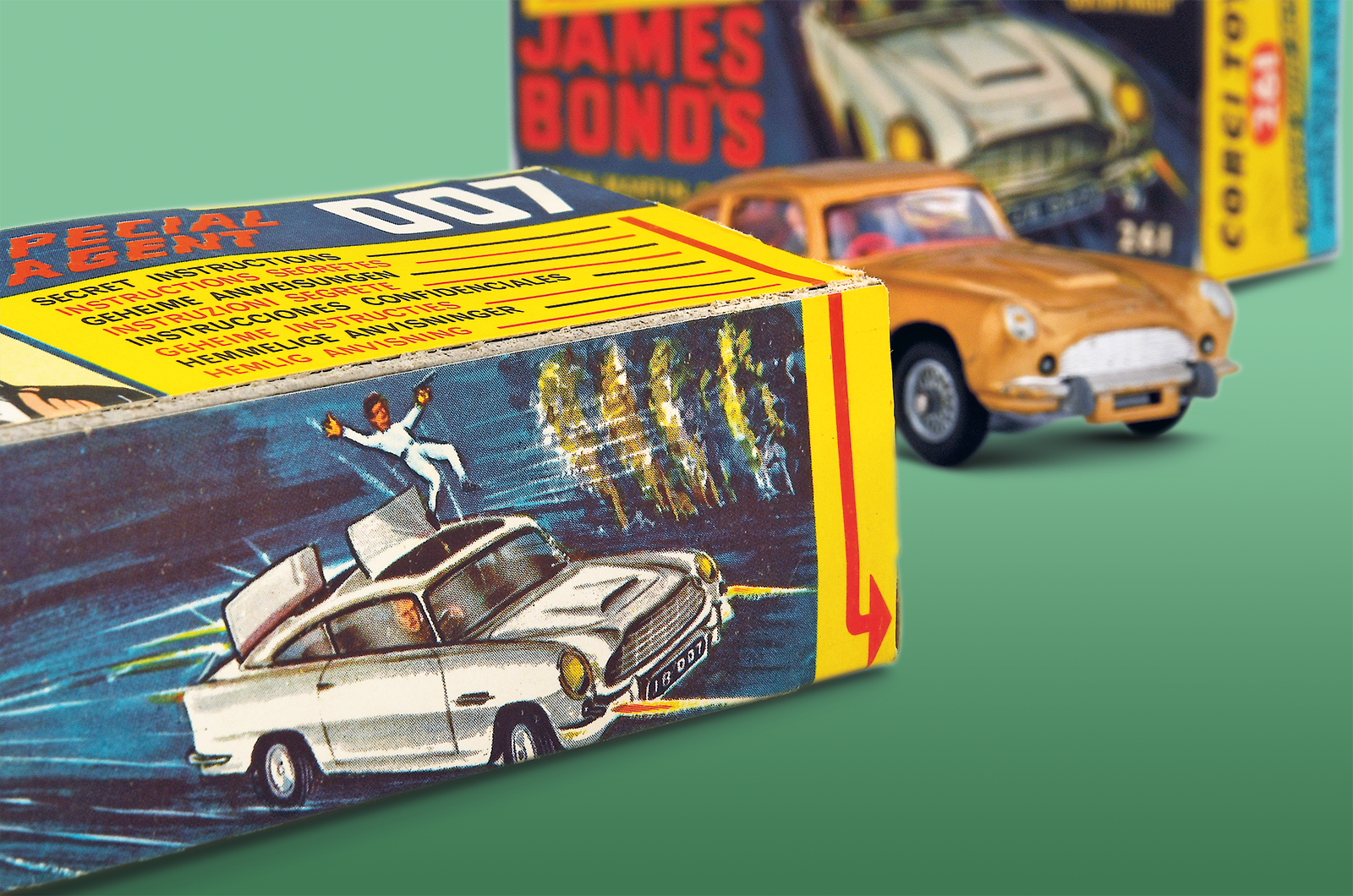

The Corgi Toys replica of James Bond’s Aston Martin DB5 from Goldfinger was made by Mettoy, the brand’s parent, at its Swansea factory. The clamour led to workers’ shifts extending late into the night, with lorries on standby to deliver by morning.

The factory could produce about 10,000 daily, each with 28 components. Fiddly assembly by hand was the only option. The cars were sprayed in gold enamel, rather than the authentic silver, which was perceived as unpainted and unworthy of the 10-shilling price.

Regardless, it suited the smash-hit’s title. The frazzled production line (almost entirely female, chosen for their nimble fingerwork) got 750,000 into shops before Christmas Eve. But that was only the start: almost four million had been sold by 1970.

Gold paintwork matched the name if not the car in the film

Improbably, the world’s most famous toy car almost didn’t happen at all. And but for the skills of these two men, reunited today, its joyful, action-packed features could never have sprung to life.