The clutch is smooth and there’s a sportily short-throw gearlever – although a column change could be specified.

The unservoed brakes come in more softly – lacking the immediacy of those on the Wolseley – but are up to the job.

Despite the Singer’s flexible engine, it’s trumped by the Wolseley in the steering department

Yet if the Singer makes a convincing case with its drivetrain, it doesn’t have it all its own way.

The steering is slower and less communicative than that of the Wolseley, while, despite a front anti-roll bar, the Gazelle leans more and rides in a softer and slightly under-damped fashion.

The Singer holds the road well enough, although it feels bigger and less poised than the Wolseley – albeit more modern, faster and ultimately more sporting, at least as far as performance goes.

Which to choose? In some ways the Singer is identifiably superior – and from youthful experience, I know how these cars can be dramatically improved by fitting Koni dampers or similar.

As it stands, though, the Wolseley may lack the Singer’s verve but it has its own sporting side, thanks to its crisp steering and general tautness of feel.

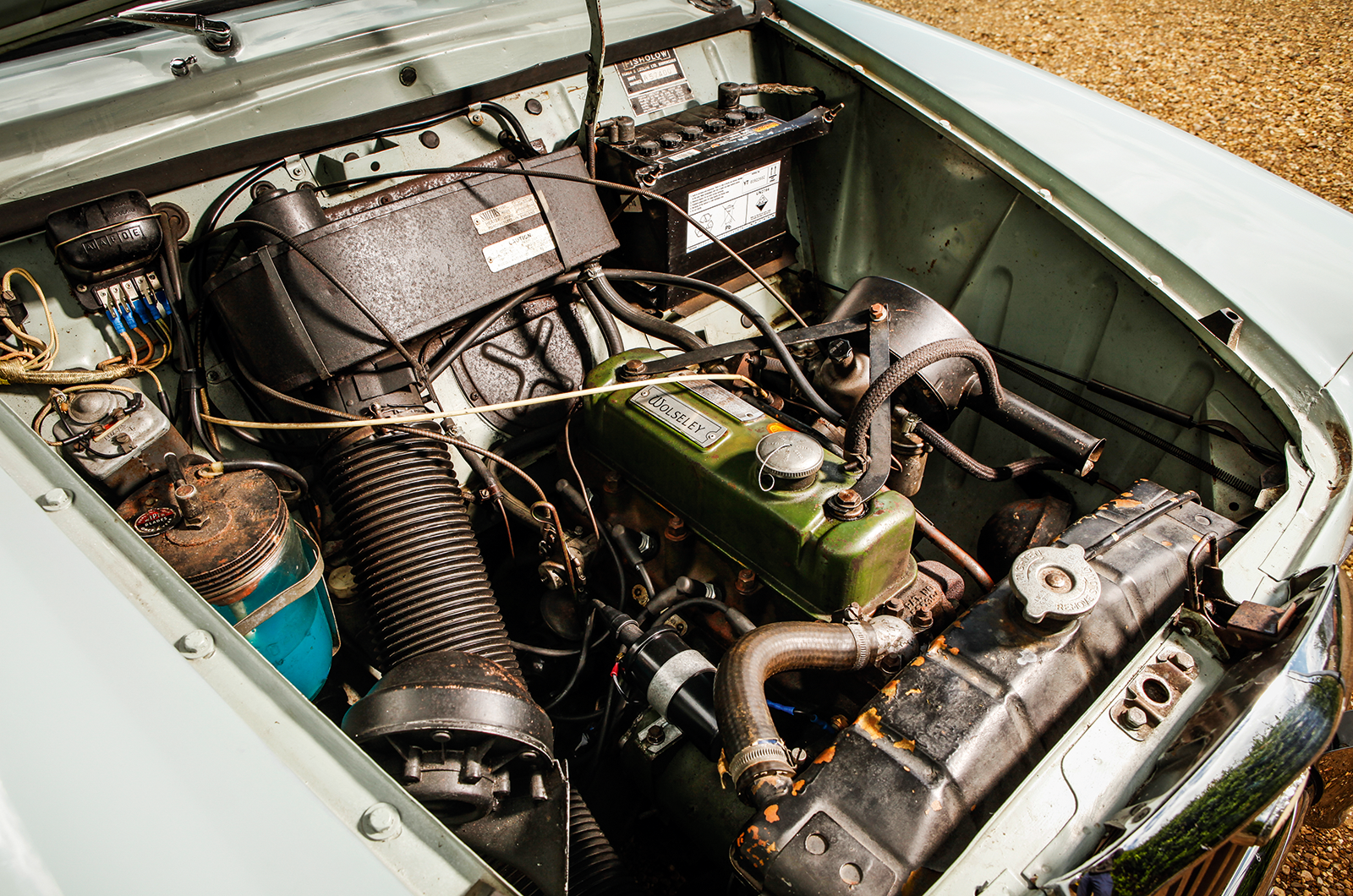

It also has a certain old-fashionedness that I find appealing, and for me that tips the balance in the BMC car’s favour.

Others, of course, might be tempted by the Singer’s more contemporary character, and vote differently.

Images: Tony Baker

Thanks to: the Wolseley Register; the Wolseley Owners’ Club; the Association of Singer Car Owners and the Singer Owners’ Club

This is from our October 2014 magazine; all information was correct at the date of original publication

Evolution not revolution

The Singer (right) and the Wolseley remained largely the same and received few updates during their lives

Both the Singer and the Wolseley changed little during their lifetimes.

The 1500 in particular underwent barely more than a few minor cosmetic tweaks.

In May 1960, the bonnet and boot gained concealed hinges; in October 1961, the model was given lowered suspension, new side grilles with round indicator/sidelight units, and Austin A40 Farina tail-lights; for 1963, there was a stiffer crankshaft and a stronger gearbox, albeit still with an unsynchronised first gear.

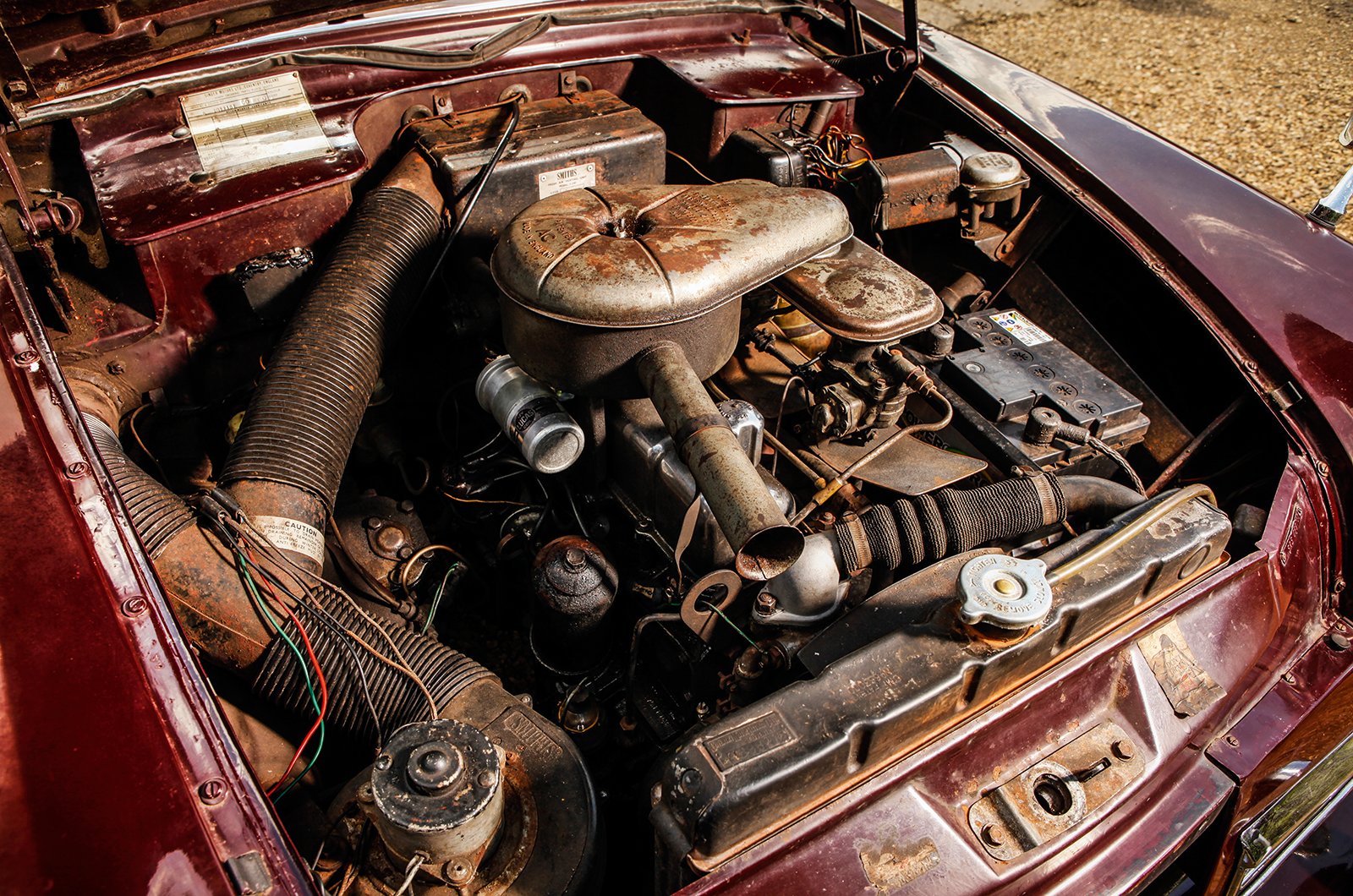

As for the Singer, after the overhead-cam Series I and Series II Gazelles and the physically identical pushrod Series III, the Series IIIA received roll-over fins and a larger front windscreen, as well as having the twin-carb engine.

After the single-carb but otherwise unchanged IIIB of August 1960 to July ’61, the IIIC of the ’62 and ’63 seasons had a 53bhp 1592cc engine.

This was carried over to the Series V, introduced in September 1963, which had a revised square-roof glasshouse, plus front discs and 13in wheels, along with a new dash.

An all-synchro ’box came in for ’65 and, for the Audax Gazelle’s last year, the Series VI had a 1725cc engine and a new lowline grille.

Convertible Gazelles were available until February 1962, and estates in Series II through to Series IIIC formats.

Enjoy more of the world’s best classic car content every month when you subscribe to C&SC – get our latest deals here

READ MORE

The battle for middle England: Rover 3-Litre vs Wolseley 6/99

Keeping up appearances: Ford vs Vauxhall vs Hillman vs Singer vs Humber vs Riley

Also in my garage: a fascination for the ’50s

Jon Pressnell

Jon Pressnell is a contributor to Classic & Sports Car