-

© Classic & Sports Car archive

© Classic & Sports Car archive -

© Classic & Sports Car archive

© Classic & Sports Car archive -

© Classic & Sports Car archive

© Classic & Sports Car archive -

© Classic & Sports Car archive

© Classic & Sports Car archive -

© Classic & Sports Car archive

© Classic & Sports Car archive -

© Classic & Sports Car archive

© Classic & Sports Car archive -

© Classic & Sports Car archive

© Classic & Sports Car archive -

© Classic & Sports Car archive

© Classic & Sports Car archive -

© Classic & Sports Car archive

© Classic & Sports Car archive -

© Classic & Sports Car archive

© Classic & Sports Car archive -

© Classic & Sports Car archive

© Classic & Sports Car archive

-

Wacky cars from France

There’s no particular reason to believe that the French are any more unorthodox than anyone else.

Until, that is, you get to their cars. Only the French could have devised the Citroën 2CV and sold it like hot croissants.

No other country could have accepted so readily the quirkiness of planes-to-cars luminary Gabriel Voisin, or Panhard body man Louis Bionier.

Maybe it’s something to do with a nation that has always valued its engineers, or its pioneering role in both the automotive and aeronautical industries.

Indeed, it was when these two strands were woven together – most notably in the aero-fetishist 1930s – that some of the wildest Gallic creations saw the light of day.

France was not unique in going streamline-crazy, but it can legitimately claim to have flown the flag of eccentricity with more vigour than any other country in the years straight after WW2.

Of all the major car-making nations, France was worst affected by the war, being defeated, occupied, divided, oppressed and bled dry.

Back on its feet and with a degree of optimism, it perhaps expressed this in an exuberance more untrammelled than anything in back-to-business Britain’s newfound socialist austerity.

Historians can debate that one. Meanwhile, here’s the evidence that some weird (and wonderful!) classic cars have been created in France.

-

1. Renault 600/900 (1957-’60)

These bizarre proposals explored how much passenger room could be crammed into the least space, while retaining a rear engine.

The 600 (on right), powered by a Dauphine ‘four’ moved ahead of the back axle, looked like the product of an illicit liaison between a Fiat Multipla and a Floride.

Credited to Ghia, it was followed by two 900s, using a bonded aluminium monocoque.

Power came from a 1700cc V8.

The first car was rear-engined and apparently had scary roadholding, so the V8 was moved amidships in the ‘MkII’.

But the forward-control design meant that the driver and passenger were too close to any potential crash.

Anorak fact The V8 was in effect a pair of 850cc Dauphine top ends united around a new alloy block

-

2. Brandt Reine (1948)

A hyper-large six-seater Isetta is one way of describing the Brandt Reine 1950, to give the car its full name.

Sitting on an impressively long wheelbase, the Brandt had no side doors.

Instead, the front and rear panels swung up to allow access to two rows of single seats, separated by a central aisle.

The powerpack was literally that: a cylindrical package, mounted transversely and driving the front wheels, and based on an opposed-piston 935cc fuel-injected two-stroke.

The Brandt also sported a windscreen angled so that rain was supposedly dispersed by wind pressure alone, ellipsoid ‘anti-dazzle’ headlamps, and brakes with novel radial linings.

Just the one car was built.

Anorak fact The Reine’s engine was claimed to develop up to 75bhp. This was said to give the 1300lb (590kg) Brandt a top speed of more than 100mph

-

3. Voisin Biscooter (1949-’58)

The rump of his firm absorbed into a nationalised aero-industry combine, Gabriel Voisin carried on designing vehicles after WW2.

The only one to see production was the Biscooter.

The ultra-lightweight aluminium monocoque runaround was powered by a Gnome et Rhône ‘twin’ driving the front wheels.

Anorak fact Parent company SNECMA refused to make Voisin’s ‘rollerskate’ and he sold the rights to Spain, where c12,000 Biscuters were made from 1953-’58

-

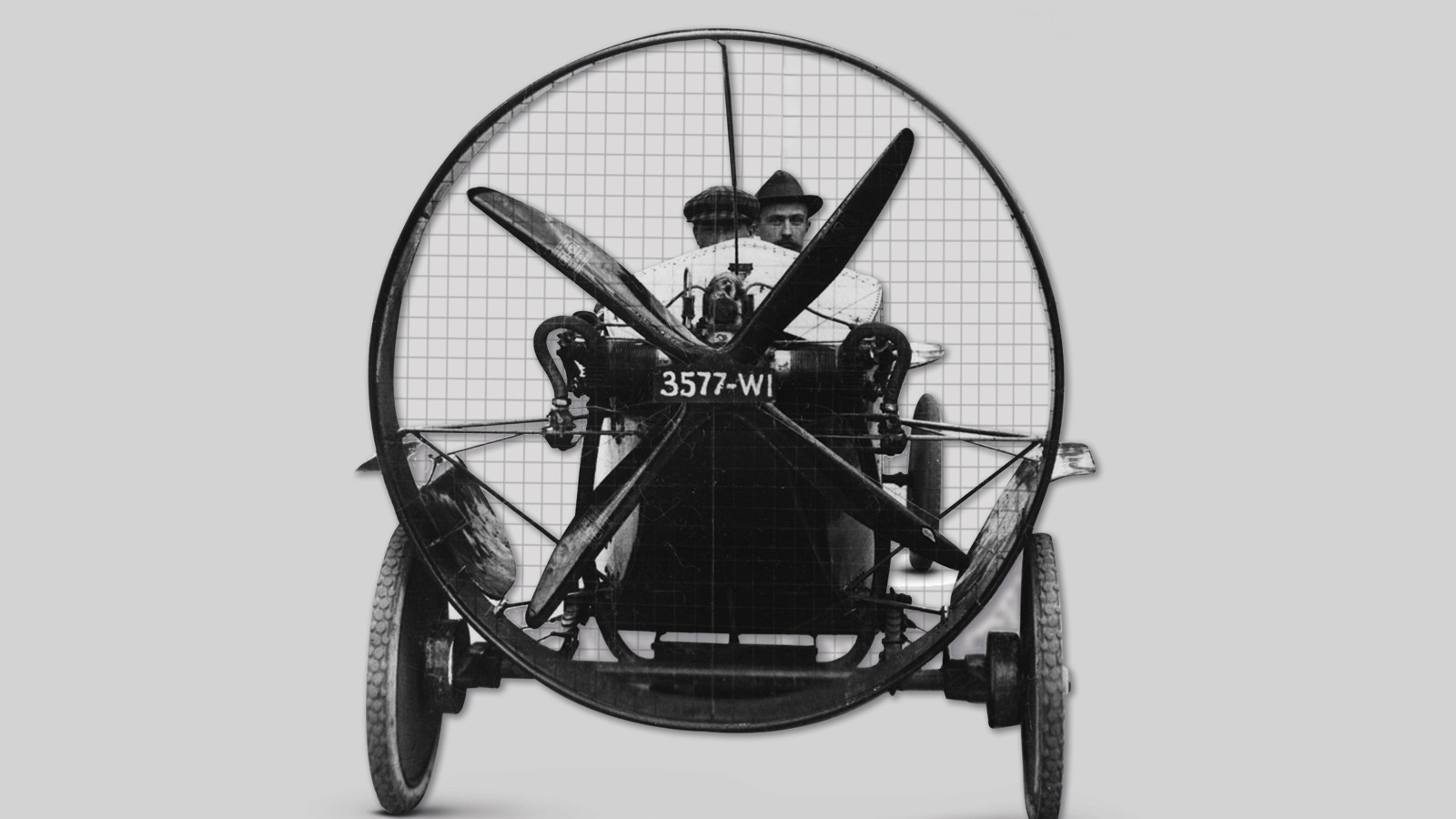

4. Leyat (1919-’25)

Few ideas are madder than a propeller-powered car.

But for Marcel Leyat his Hélica was eminently logical.

Drive by propeller meant no need for a transmission; a fuselage-like wooden monocoque meant light weight and aerodynamic efficiency; steering from the rear was simpler, with less chance of losing control after a blowout; brakes on only the front axle meant stable braking uncorrupted by steering reactions; and the narrow rear axle improved manoeuvrability.

Despite an alleged 600 orders, only about 30 Leyats were built.

I’ve driven the sole working survivor; it was one of the scariest experiences of my life.

Anorak fact Leyat mooted versions that could be converted into an aeroplane or hydroplane, or fitted with flanged wheels or snow-skis

-

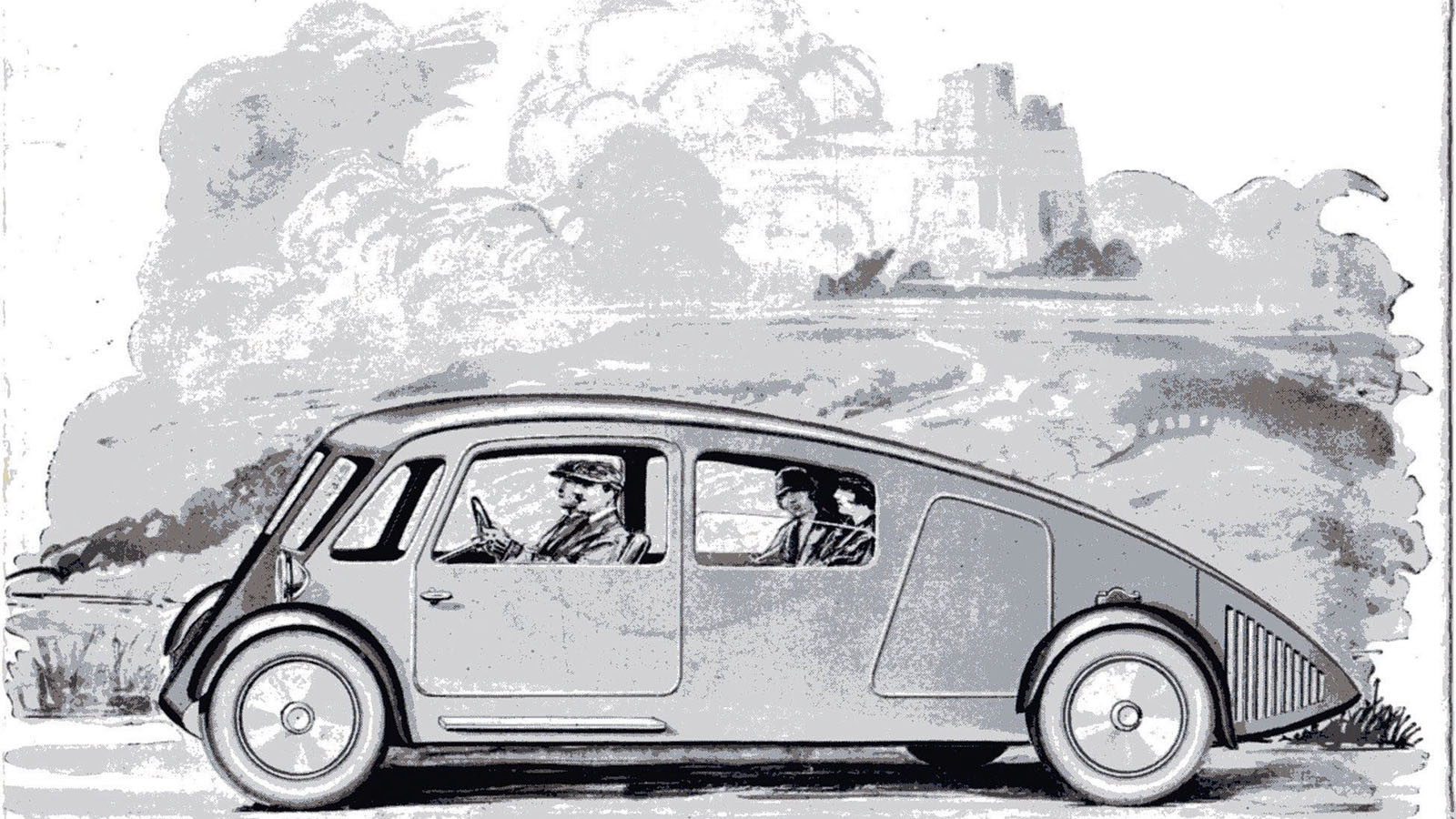

5. Peugeot 402 Andreau (1936-’38)

Dominated by its huge dorsal fin, Peugeot’s extraordinary 402-based streamliner plays the functional-purity card for all its worth, ticking every box in the lexicon of aerodynamic correctness.

It’s the real deal, too.

In 1986 the car was wind-tunnel-tested, and clocked a 0.364Cd: better than the 0.37 of a late-model Citroën DS.

Top aerodynamicist Jean Andreau was behind the car, the first example of which was shown at the 1936 Paris salon.

Possibly seen as having a V8, were it ever to reach series production, the Andreau was admirable publicity for the aero-look 302 and 402.

Sober old Peugeot was more concerned with launching its small 202 than taking a risk on a futurist V8 supersaloon, though.

Anorak fact It was decided to make a few customer cars after the 1936 show. Of the six chassis numbers allocated, it seems only two vehicles were built

-

6. Citroën C1/C10 Coccinelle (1956-’58)

While Renault was tinkering with prototypes that put everything at the rear, Citroën’s André Lefèbvre was doing exactly the opposite.

With his C1 he put all the weight to the front and reduced the rear to two tiny unbraked wheels not even 2ft apart – all very Leyat.

When a tester put the car on its roof, Lefèbvre realised he’d gone a bit too far and, after rejigging the suspension of the C1, he moved on to the more practical C10.

This featured a bonded aluminium structure and boasted a mathematically calculated form that gave a Cd of 0.23.

Suspension was hydropneumatic, as on the C1, and the C10 was good for 70mph or so with an enlarged 2CV ‘twin’.

But despite its many clever features, the C10 was never going to be more than a testbed.

Citroën had its hands full trying to make the DS reliable, and certainly couldn’t afford to take the wild leap into the future the Coccinelle represented.

Instead it reclothed the Deux Chevaux as the Ami 6, and laughed all the way to the bank when the oddball Ami became France’s best-selling car.

Anorak fact The front of both vehicles incorporated a curved Plexiglas dome with a full-width opening at eye level and a flat fold-down windscreen behind. Above 30mph the dome directed wind – and rain – over the ’screen, which could then be folded flat for open-air motoring

-

7. Claveau CIR9 (1926-’27)

Emile Claveau specialised in quirky no-hopers: his last design was 1955’s streamlined DKW-powered 56, said to have a 0.23Cd, preceded by the elephantine V8 Descartes saloon of ’48.

Claveau’s water-cooled Autobloc prototype of 1926 – rear-engined, monocoque and of the school of Rumpler – gave way to an air-cooled design in ’27.

At this stage the deliciously avant-garde closed CIR9 was shown, powered by the same 1500cc flat-four.

Its fuselage-style looks were just too freaky to fit in to a world of sit-up-and-beg Renaults, Peugeots and Citroëns.

Anorak fact In 1930 Claveau showed a front-wheel-drive runabout, but it never reached production

-

8. Wimille (1945-’50)

A smooth-lined mid-engined GT powered by a V8 and seating three abreast, with a central driving position: doesn’t sound all that dodgy an idea, does it?

In fact there are shades of the McLaren F1 about the car, created by top French racer Jean-Pierre Wimille.

But the problem with the Wimille, styled in its definitive form (above, on right) by Philippe Charbonneaux, was that it was simply too ahead of its time, and too irrelevant to the needs of the French market.

Even without Wimille’s death in ’49 the project would inevitably have run out of steam.

Anorak fact It was hoped that the car would be sold as a range-topper by engine supplier Ford of France

-

9. Mathis 666 (1948-’49)

Having abandoned his 333, Emile Mathis turned to a more conventional approach for his 2840cc water-cooled flat-six 666.

With a strange mix of straight lines and curves, the body incorporated a Vutotal pillarless windscreen and a panoramic rear window.

Perhaps the rear-drive 666 was aesthetically too radical, because for the 1949 Paris Salon Mathis showed a chassis with a Studebaker-like ‘spinner’ front, plus artwork of altogether more conservative coachwork, drawn up by Chapron and by Saoutchik.

Anorak fact The name 666 signifies six seats, six cylinders and (thanks to overdrive) six speeds

-

10. Symétric (1951-’58)

Leg-pull, hoax, or just the product of a bunch of eccentrics? Nobody’s quite made their mind up about the Symétric.

The design initially lived up to its name, having a symmetrical cylinder-shaped glasshouse with full-height sliding doors.

A Simca Eight engine was mounted transversely at the front, and transmission to all four wheels was said to be ‘thermo-electric’: the engine drove a dynamo that fed electricity to a motor at each wheel.

The project was taken over by a new enterprise, Arbel, which showed a restyled Symétric in ’58 (above), supposedly with a choice of a rotary internal-combustion engine, a diesel-powered electric generator... or a nuclear source.

The body was said to be of Polystic, the electric transmission was tagged Electric-Drive, and the rubber-and-aluminium suspension revelled in the name Thermogum. Trippy stuff!

Anorak fact There was just one pedal on the original car: when pressed, the hydraulic and electric braking systems released, whereas lifting one’s foot applied the anchors