-

© Tony Baker/Classic & Sports Car

© Tony Baker/Classic & Sports Car -

© Classic & Sports Car

© Classic & Sports Car -

© British Motor Industry Heritage Trust

© British Motor Industry Heritage Trust -

© Citroën

© Citroën -

© Classic & Sports Car

© Classic & Sports Car -

© Ford

© Ford -

© Classic & Sports Car

© Classic & Sports Car -

© British Motor Industry Heritage Trust

© British Motor Industry Heritage Trust -

© Citroën

© Citroën -

© Haymarket Automotive

© Haymarket Automotive -

© Tony Baker/Classic & Sports Car

© Tony Baker/Classic & Sports Car

-

Those eleventh-hour tweaks

For most of the history of the motor car, there have been examples of last-minute changes to improve a product before it reaches the public – often when tooling is well down the line.

Perhaps the most obvious is the decision by Alec Issigonis to widen the Morris Minor by 4in, at that very stage, resulting in a flat raised section in the bonnet of exactly that width… plus bumpers cut in two and extended with a crude bolted-in fillet. And Austin nearly went down the same route: the two-door Dorset was going to have a body 4in narrower than that of the four-door Devon.

These are the sort of things that make production engineers – and cost-accountants – tear their hair out.

When the wedge-shaped rear side window approved for the Ford Capri was altered to become that emblematic horseshoe shape – after much of the tooling had been finalised – the Dagenham bean-counters must have been crying into their light and bitter.

The point, though, is that in all – or almost all – of the instances quoted here, the result has been a better car. In most cases, indeed, the company concerned has pulled itself back from the brink of likely disaster.

First thoughts aren’t always best – read on!

-

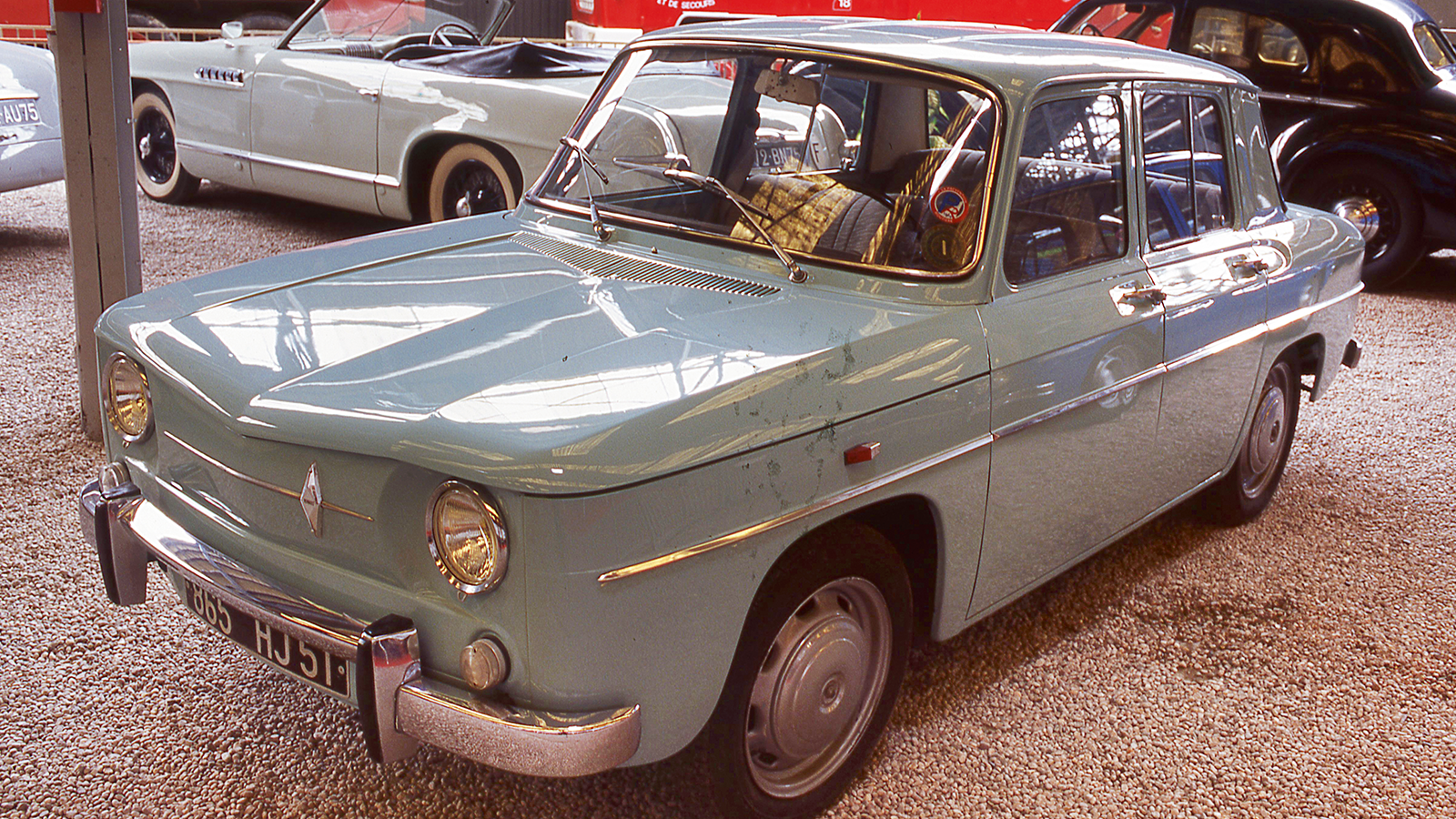

1. Renault 8

When the production-ready R8 was shown to the sales department in September 1960, the gawky prototype was given a unanimous thumbs-down.

With the rival Simca 1000 on the horizon, and a mid-’62 start-up planned, a panic-stricken Renault called in independent designer Philippe Charbonneaux to do a drastic restyle, keeping all the existing hard points. In just three weeks, Charbonneaux rejigged what he described as “a complete hash-up”, working day and night with a team of fabricators.

“Not a single measurement was made,” he recalled in a 1996 interview. “I had a big blackboard and explained with chalk lines how to change things, and all the new panels were formed by hand. When it was finished, the sales department accepted it unanimously.”

Anorak fact: Charbonneaux was a prolific industrial designer, creating everything from toothbrushes and fountain pens to television sets. One of his most famous creations, still in production, is the Nénette car-polishing brush

-

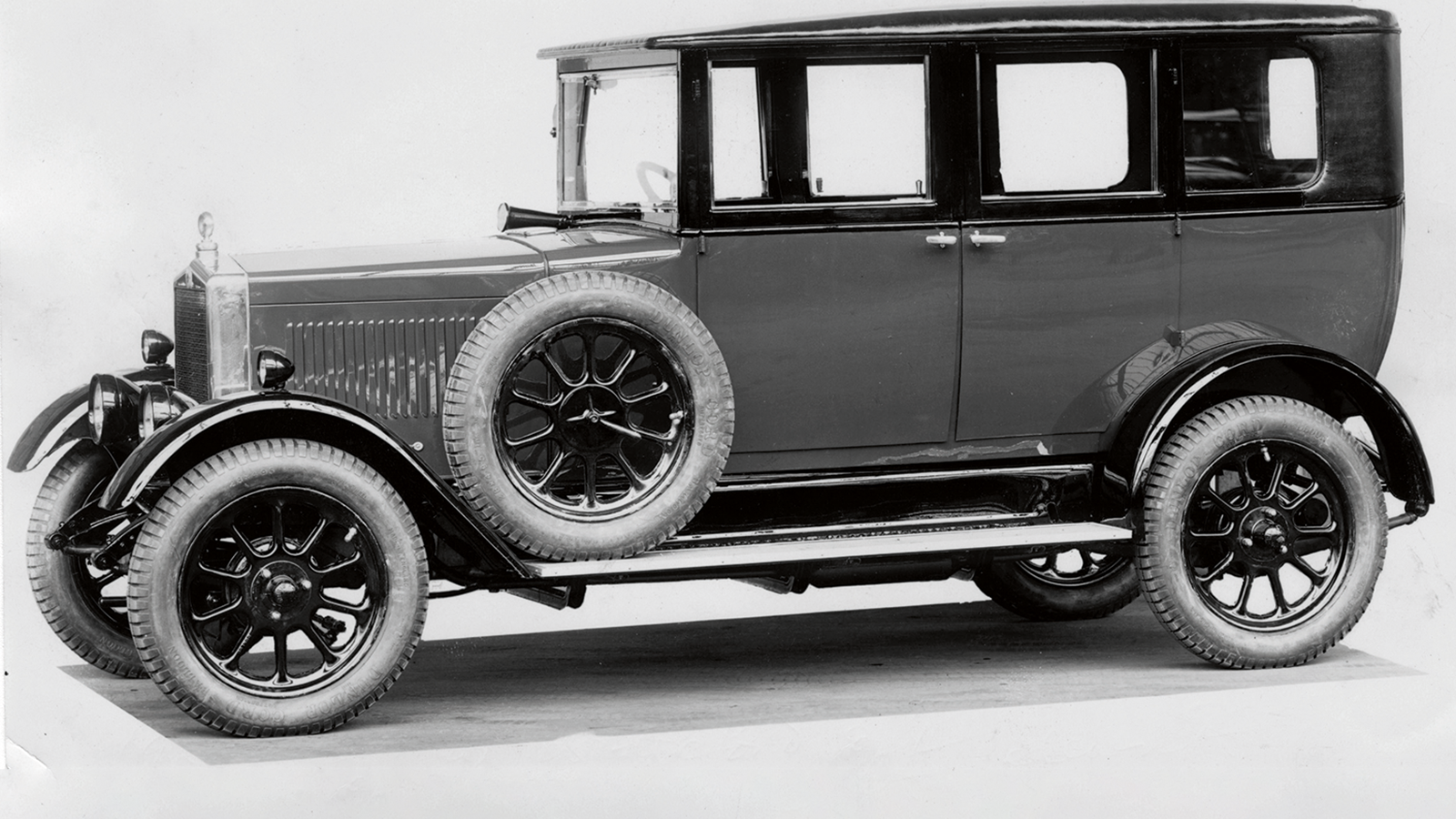

2. Morris Six

After an attempted six-cylinder version of the Bullnose had proved a catastrophe, Morris tried again in 1927, with a six-pot Flatnose called the Light Six. It had a new overhead-cam engine, but the rest was cobbled together from existing componentry.

The chassis was the basic Oxford ladder frame, its wheelbase stretched but with the track unchanged. At 4ft front and rear, it was a narrow-gutted car that wouldn’t hold the road.

After its unveiling at the Motor Show, the Light Six was rapidly tweaked, being given a new lower-slung chassis with tracks a full 8in wider. Relaunched in March ’28 as the Morris Six, the car had a mixed reception from the press, the brakes and steering in particular being criticised.

Just 3470 were made, over two model years, before the Six gave way to the Isis in mid 1929.

Anorak fact: The narrow-chassis Light Six formed the basis of the MG 18/80, but with a new and suitably rigid frame

-

3. Citroën Traction Avant

André Citroën knew he had to launch the Traction Avant before his money ran out. He also knew that he had to invest heavily in a new plant, and that the car had to be so technically advanced that it would not need replacing for many years.

Part of the spec was to be a fully automatic single-speed transmission devised by Dmitri Sensaud de Lavaud, Citroën springing this decision on his engineers in autumn 1933. But the ‘turbine’ didn’t work: the prototypes couldn’t climb hills without substantial performance loss and massive overheating of the transmission oil.

In March 1934, just one month ahead of the Traction’s announcement, the ‘turbine’ was abandoned in favour of an orthodox three-speeder.

Hurriedly designed using parts from the rear-drive Citroëns, and crammed into the housing intended for the automatic gearbox, it was to constitute one of the car’s enduring weaknesses.

Anorak fact: Sensaud de Lavaud was an inveterate inventor, whose patents spanned a rotary engine to a way of moulding handbags

-

4. Goggomobil T600/700

Re-engineering a car from front- to rear-drive at the last stroke of the clock is pretty radical. But that’s what Goggomobil maker Glas did.

At the Frankfurt show in ’57, the prototype T600 – there was then no T700 – had front-wheel drive and independent rear suspension. Yet the lightly restyled model that was put on sale nine months later had drive to the rear wheels and a leaf-sprung live back axle.

Front-wheel drive had been abandoned supposedly because of nose-heavy handling – but rear drive would also have lowered production costs.

It made the Goggo the only German small car with this configuration: a marketing advantage, it was felt, because it aligned the T600 with bigger and more prestigious cars.

Anorak fact: The T600/700’s flat-twin was the work of former BMW engineer Leonhard Ischinger, responsible for the all-alloy V8 fitted to the 501/502 ‘Baroque Angel’

-

5. Ford Cortina MkI

Part of the Cortina’s success – against porky competitors such as the Minx and Cambridge – was down to strong styling. A key component was the round tail-lights, with their three-part ‘Ban the Bomb’ design echoing the emblem of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

The car nearly went into production with a more anodyne rear treatment, however. The Cortina’s lines had been signed off in November 1960, but in January ’61 a Ford high-up decreed that the slanting lights of the accepted cluster be replaced by round units – in tune with those on US Fords of the time.

Tooling for the rear panel was already under way, so the dihedral shape of the rear wing and bootlid was not changed. Despite this, Charles Thompson’s new round lamps looked as if they had been there from the start.

Anorak fact: Mock-ups before the dihedral lamps featured slanting vertical units along the lines of those on the big MkIII Fords

-

6. Kaiser and Frazer saloons

When construction and shipbuilding magnate Henry Kaiser and motor-industry dynamo Joe Frazer got together, the idea was that there would be two contrasting cars using the same body pressings.

The monocoque Kaiser would have front-wheel drive and all-round torsion-bar suspension, while the rear-drive Frazer would sit on a separate chassis with a coil-sprung front and a leaf-sprung rear.

Prototypes were shown in January 1946, but the Kaiser suffered from transmission problems and dramatically heavy steering. Nor did it make sense to offer two models with totally different engineering.

Notwithstanding K-F having over 250,000 orders for FWD Kaisers in its corporate top pocket, front drive was abandoned – at a stage when the body dies had arrived. When the cars reached production, the Kaiser was merely a lower-cost Frazer.

Anorak fact: It seems the decision to drop FWD was taken only in May 1946, yet manufacture of rear-drive cars began the following month

-

7. Mini Metro

By summer 1977, the long-awaited replacement for the Mini was in effect signed off. Fully engineered prototypes were being built, on temporary tooling.

Then came three styling clinics in Europe – British Leyland being latecomers to this way of validating or otherwise the acceptability of a car’s styling. At each one of these clinics, ADO 88 bombed. With a planned autumn ’79 launch, key tooling had already been commissioned.

Yet BL could not afford to have its life-saving new model anything but as right as possible. So a crash redesign took place over three months, under the direction of ex-Rover man David Bache. The car was made more stylish and more upmarket by modifying every skin panel, while keeping the maximum unchanged underneath.

As a consequence, the launch of what was by then coded LC8 was delayed by a year.

Anorak fact: To keep the press guessing, much final development testing of the Metro was carried out using the older ADO 88 prototypes

-

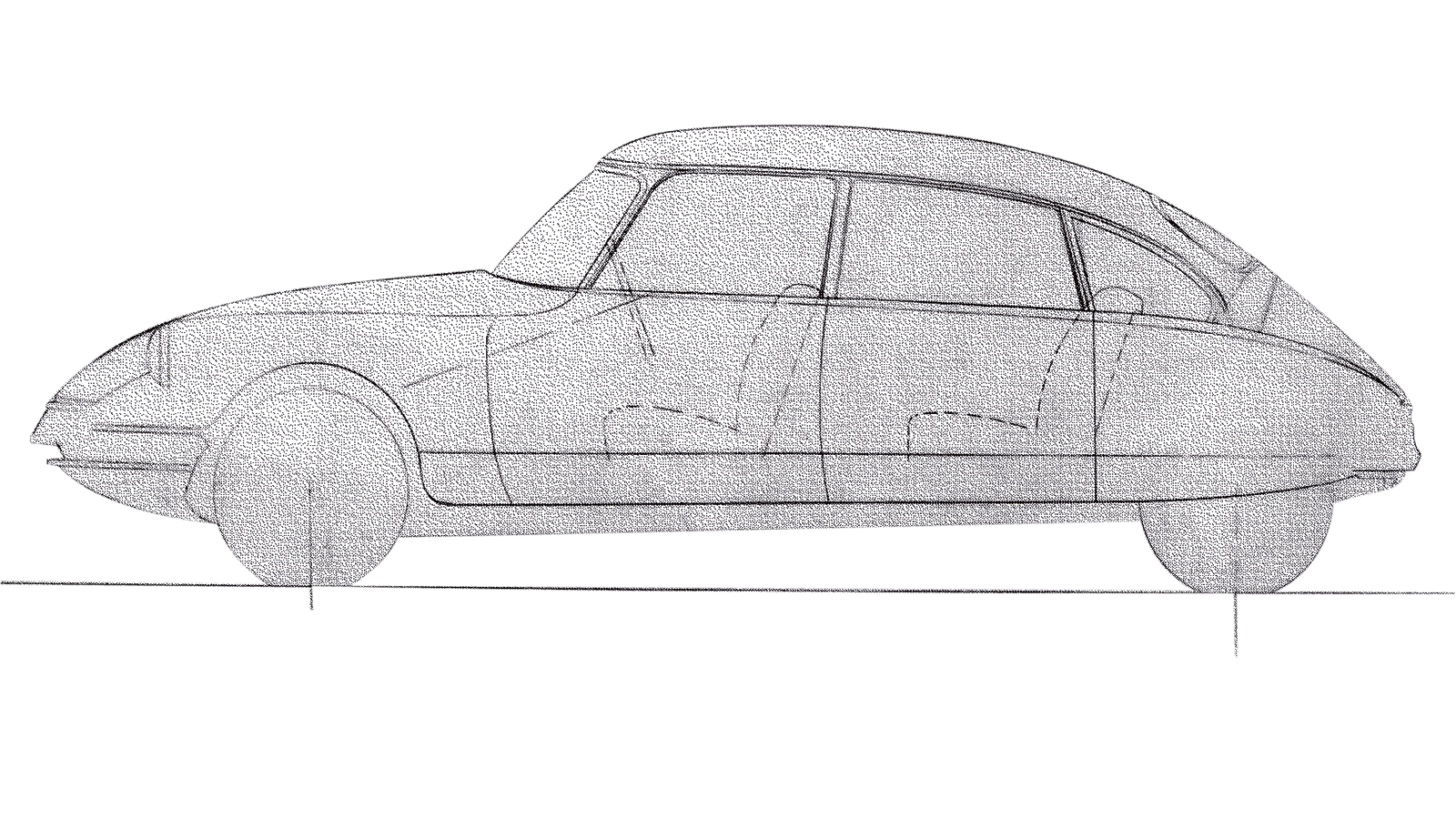

8. Citroën DS

With tooling well down the line, in summer 1954 Citroën got cold feet about the styling of the DS. At this stage it had a six-light fastback configuration with a beetle-back rear, but company top brass was worried that softer shapes were on the way out.

A last-minute revamp by stylist Flaminio Bertoni – begun in late 1954 – accordingly transformed the DS from a slightly bulky profile into a rather more elegant four-light treatment. Requiring minimal tooling changes, this brought with it a raised rear roofline that sat ill with the shallow rear window.

The solution was a stroke of genius: roof-mounted ‘chip-cone’ indicators that took the eye away from this visual step and at the same time added definition to the rear of the car.

Anorak fact: Some early versions of the DS had longer chromed indicator housings that flowed into the guttering; these were nicknamed trompettes de Jéricho

-

9. Triumph TR2

In early 1952, Standard-Triumph boss Sir John Black ordered his engineers to come up with a sports car in time for that year’s Motor Show – only months away.

The result was an ugly little pug cobbled together in eight weeks from whatever was available: a chassis based on that of the ’36 Standard Nine, a Vanguard engine and gearbox, plus Mayflower front suspension and rear axle. This unholy mish-mash was never going to compete with the Healey 100, and it drove like a pig.

Having given his forthright views, former BRM test-driver Ken Richardson was drafted in to supervise an overhaul. All the mechanicals were revised, a new chassis was drawn up, and the body was restyled to eliminate the prototype’s stubby tail.

Unveiled at Geneva in ’53, this was the definitive TR2 – and the start of a long and successful line.

Anorak fact: A Nine chassis was used because a stock was unearthed in the bowels of the plant

-

10. Jensen Interceptor

Jensen knew that it had to replace the oddball CV-8 coupé with something less aesthetically controversial. The result was a resolutely dated convertible that revived the Interceptor name.

Unveiled at the 1965 Earls Court show, under its aluminium skin it had a Chrysler V8 and a de Dion rear axle. A hardtop version followed, but by the time it was registered in January 1967, the project, coded P-66, was as dead as could be.

Quite simply, the young new guard at Jensen, led by much-respected chief engineer Kevin Beattie, felt that the Jensen brothers and their long-time stylist Eric Neale were too far out of touch with modern trends.

They had their way, and Touring came up with the delightful glassback Interceptor/FF for the 1966 show.

Anorak fact: The Interceptor and P-66 employed a windscreen and side glasses adapted from those of the Big Healey