-

© Will Williams/Classic & Sports Car

© Will Williams/Classic & Sports Car -

© RM Sotheby’s

© RM Sotheby’s -

© Ford

© Ford -

© Tom Gidden/RM Sotheby’s

© Tom Gidden/RM Sotheby’s -

© Kev22/Creative Commons licence https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode.en

© Kev22/Creative Commons licence https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode.en -

© Thesupermat/Creative Commons licence https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode.en

© Thesupermat/Creative Commons licence https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode.en -

© James Mann/Classic & Sports Car

© James Mann/Classic & Sports Car -

© Darin Schnabel/RM Sotheby’s

© Darin Schnabel/RM Sotheby’s -

© Darin Schnabel/RM Sotheby’s

© Darin Schnabel/RM Sotheby’s -

© Darin Schnabel/RM Sotheby’s

© Darin Schnabel/RM Sotheby’s -

© Motorcar Studios/RM Sotheby’s

© Motorcar Studios/RM Sotheby’s -

© Ford

© Ford -

© Will Williams/Classic & Sports Car

© Will Williams/Classic & Sports Car -

© RM Sotheby’s

© RM Sotheby’s -

© Theodore W Pieper/RM Auctions

© Theodore W Pieper/RM Auctions -

© John Bradshaw/Classic & Sports Car

© John Bradshaw/Classic & Sports Car -

© Stellantis

© Stellantis -

© Renault

© Renault -

© Daimler AG

© Daimler AG -

© Classic & Sports Car

© Classic & Sports Car -

© Andy Morgan/Classic & Sports Car

© Andy Morgan/Classic & Sports Car -

© John Bradshaw/Classic & Sports Car

© John Bradshaw/Classic & Sports Car -

© Julian Mackie/Classic & Sports Car

© Julian Mackie/Classic & Sports Car -

© Tony Baker/Classic & Sports Car

© Tony Baker/Classic & Sports Car -

© RM Sotheby’s

© RM Sotheby’s -

© Lyndon McNeil/Classic & Sports Car

© Lyndon McNeil/Classic & Sports Car -

© Tony Baker/Classic & Sports Car

© Tony Baker/Classic & Sports Car -

© Tony Baker/Classic & Sports Car

© Tony Baker/Classic & Sports Car -

© Stellantis

© Stellantis -

© Tony Baker/Classic & Sports Car

© Tony Baker/Classic & Sports Car -

© Tony Baker/Classic & Sports Car

© Tony Baker/Classic & Sports Car

-

Motoring mania

“Cars all look the same nowadays!” is a cry you often hear, usually emitted by people who really mean that cars don’t look the way they used to when they were younger.

In fact, at any time and in any field, human artistic endeavours tend to converge to the point where non-enthusiasts find it difficult to tell them apart, whether you’re talking about aeroplanes, bars, thrash metal music, Cubist paintings or TikTok videos.

While you’re pondering over that one, here are 30 examples of automotive styling trends adopted (and sometimes, but not always, later dropped) by designers over more than a century of motoring.

For the avoidance of doubt, the cars we’re using to demonstrate each point are representative of the trend, but not necessarily the first examples.

-

1. Horseless carriage

‘Horseless carriage’ is often used as a joke term to describe a primitive early car, but in at least one case it was quite true.

Daimler’s prototype of 1886 was a carriage built by German coachbuilder Wilhelm Wimpff & Son, from which Gottlieb Daimler removed everything necessary for the attachment of a horse before adding an engine and transmission.

This was an extreme example, but many later cars – including the Oldsmobile Curved Dash (pictured), which went into production 15 years after the Daimler was built – still looked as if they had been designed on much the same principle.

-

2. Spoked wheels

For many centuries, all road vehicles had wheels which consisted of a rim and a central hub joined together by radial spokes.

The early cars used the same type, sometimes with thin steel spokes – as in the original Benz Patent Motorwagen and the 1889 Daimler Stahlradwagen – but far more often with thicker wooden ones.

The latter type was used on the Ford Model T (pictured), and indeed on so many popular cars of the same era that it’s almost impossible for a non-expert to tell one from another by its wheels alone.

-

3. Front engine

The early convention in motoring was to drive the rear wheels of a car, and to place its engine conveniently close to them.

Mounting the motor further forward was first tried in 1891 by Panhard, and is so closely associated with the French company that the front-engine, rear-wheel-drive layout is still sometimes referred to as the Panhard system.

The engine of that car was so tiny that its location made very little difference to the overall shape, but that soon changed, as demonstrated by the 1900 Panhard et Levassor pictured here.

The positioning of the engine at the front and the passengers behind it became one of the starting points of automotive design, from which almost everything else followed.

-

4. High wheelers

Some early manufacturers, particularly in the US, persisted for several years with very large-diameter wheels of the type used on horse-drawn carriages.

The cars were known colloquially as high wheelers, and examples include International Harvester’s Auto Buggy (pictured), the De Schaum Seven Little Buffaloes and the Reliable Dayton.

High wheelers became unfashionable as other marques – notably Ford with its enormously successful Model T – began using much smaller wheels, and the trend had faded away by about the time of the First World War.

-

5. Tall bodies

One of the more alarming early automotive design trends was a tendency to put very tall bodies on short and narrow cars.

In the US, Baker and Detroit Electric both adopted this style for their battery-powered models, while on the other side of the Atlantic Renault did the same for some of its petrol-engined cars, including the 1899 Type B pictured here.

The Danish composer Carl Nielsen, given one of these Renaults by a fan after being told by his doctor that his worsening heart condition made it unwise for him to continue riding horses, nicknamed his vertical vehicle the ‘sentry box’, which sums up the situation nicely.

-

6. Round headlights

Unless a coachbuilder succumbed to a wild flight of fancy, car headlights were almost always round, whether they were small units placed wherever they would fit or, as on the Bentley 3 Litre Super Sports pictured here, large affairs mounted on either side of the radiator.

With exceptions which we’ll come to later, large-scale car makers saw no reason to stray from the norm until the early 1960s, when first the Ford Taunus P3 (nicknamed Badewanne, or bath tub) and then the Citroën Ami appeared with lozenge-shaped headlights.

At the time, this would have been impossible in the United States, where round headlights were mandatory until 1975.

This long-standing trend has now all-but disappeared – today, headlight shape is a significant part of car design, and roundness is almost nowhere to be seen.

-

7. Long bonnets

Large, round headlights, mentioned earlier, were among the features which make expensive cars of the early 1910s to 1930s difficult to tell apart if you’re not already familiar with them.

Another is the long bonnet, which was forced on designers by the prevalence of lengthy engines mounted entirely behind the front axle.

Examples include the two V16s used by Cadillac during the 1930s, the V12s frequently employed by Packard (Twin Six pictured) and innumerable straight-eights, the most dramatic being the 12.8-litre unit fitted to the Bugatti Royale.

Made necessary by the engines they covered, the bonnets became stylistically distinctive – no luxury car of the period was without one, suggesting that in at least one sense, size does matter.

-

8. Prominent radiators

To large headlights and long bonnets we can add prominent radiators as the third major design feature of the classic era.

Almost perversely, Renault, and sometimes fellow French marque Clément-Bayard, hid their radiators out of sight behind the engine for many years, but nearly everyone else mounted them very visibly up front, where they could easily catch the air.

At least in this case the shape makes it easier to identify the car – even a non-expert can soon appreciate that a Rolls-Royce radiator looks quite different from one made by Bugatti or Delage (D8-100 pictured).

As aerodynamics became an increasingly important part of car design, the disadvantage of plonking a large piece of metal smack in the airstream became obvious, and radiators were eventually brought inside the bodywork, where only as much air as was absolutely necessary was channelled towards them.

-

9. Underslung chassis

We now divert briefly from the main point of this feature to highlight a trend which, for some reason, was almost ignored for many years – that of placing a car’s chassis under the front and rear axles rather than above them, in the interests of lowering the centre of gravity.

Wolseley and Renault tried this with their racing cars in 1902 and 1905 respectively, but soon abandoned the idea.

Shortly afterwards, US companies American (1908 50hp Roadster pictured) and Regal both began producing underslung road cars which, because of their unusual stance, looked far sportier than almost anything else available at the time.

The benefits of building such low cars were either ignored – probably because the highways of the time were so rough that it was advisable to have plenty of ground clearance – or not understood, and it would be a long time before such road-hugging machines became common.

-

10. Custom bodies

In the days when bodies could be removed from cars without undue disturbance, it was common for wealthier customers to have them replaced by ones produced by specialist coachbuilders, or in many cases for manufacturers to assume this was going to happen and not supply a body at all.

Companies such as Figoni et Falaschi (1938 Talbot-Lago ‘Teardrop’ Coupé pictured) and Saoutchik produced extravagant designs, and it’s possible at least to make a reasonable guess about their creators once you’ve seen a few examples of their work.

This becomes harder when the bodies, while still elegant, have a more sober design, so today it takes experience to able to tell a Barker from a Mulliner from a Park Ward as easily as motorists were able to when they were fashionable.

Coachbuilding became impossible when unibody construction (in which the body is the basic structure to which everything else is directly or indirectly attached) became almost universal after the Second World War.

-

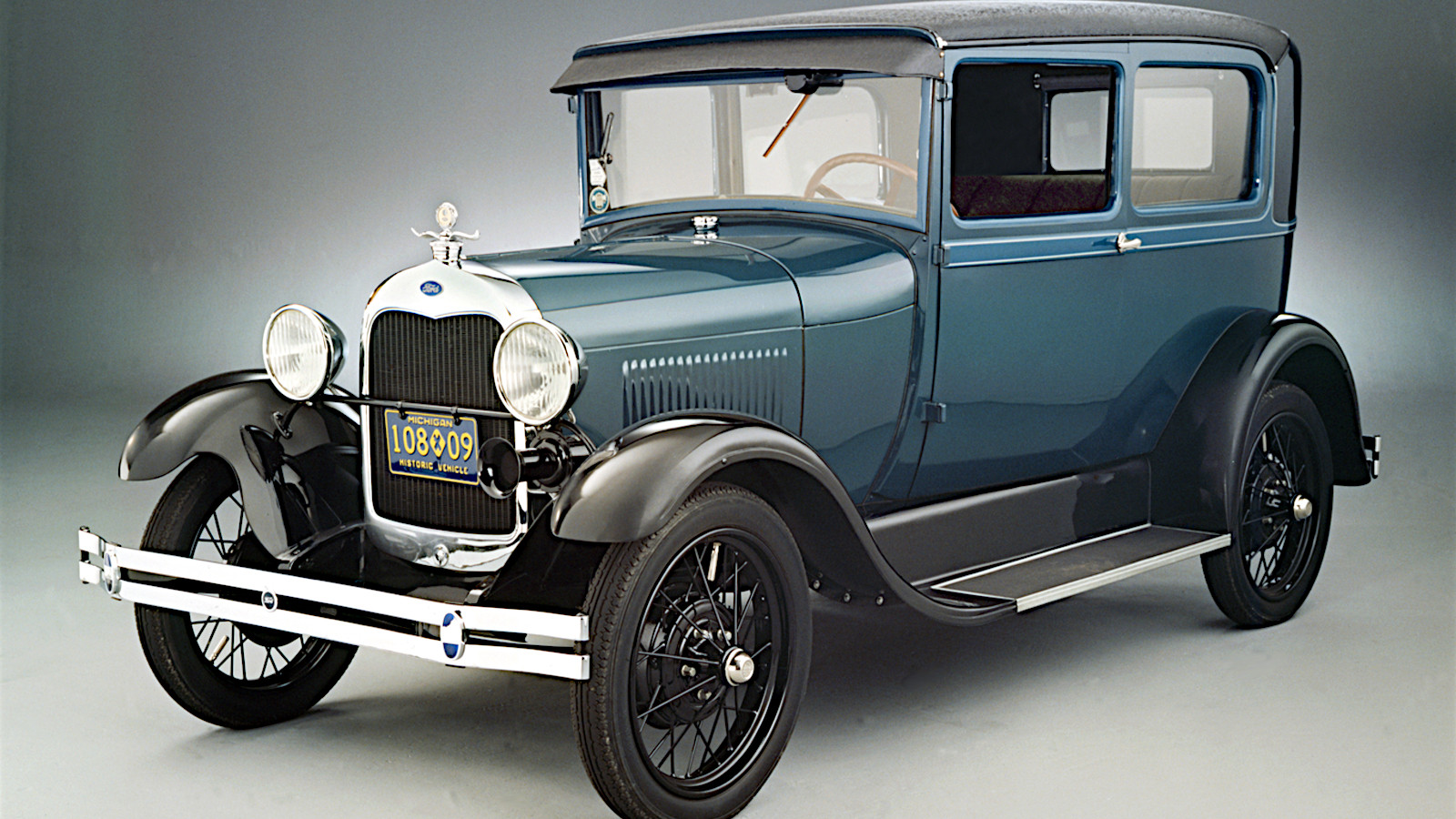

11. Running boards

Now used mostly on pick-up trucks and large SUVs, running boards were once so common on cars in general that it was impossible to identify a particular model simply because it had them.

At first, running boards, such as those seen on the Ford Model A pictured here, made it possible to get from a high body mounted above the chassis to the ground without having to jump.

As bodies became lower, the need for running boards became less obvious, but with rare exceptions (such as the Cord 810 and 812 of the 1930s) manufacturers continued to fit them – partly, no doubt, because the public expected this to happen.

-

12. Streamlining

After some experimenting in the previous decades, streamlining hit the motor industry in a big way in 1934 when the Chrysler and De Soto Airflows, the Hupmobile Model J and the Tatra 77 were all introduced, with the Volvo PV 36 Carioca (pictured) following a year later.

The design of the rear-engined Tatra was quite distinctive, but the others, with the same mechanical layouts and the same intention to disturb the wind as little as possible, looked at first glance as if they were closely related, though Volvo has insisted that its car was not influenced by any of the American ones.

They would all look out of place on today’s roads, but aerodynamic considerations have made cars of other eras look similar to each other.

For example, the point has been made that family saloons of the 1990s (or repmobiles as they were often known) such as the Ford Mondeo, Nissan Primera, Toyota Carina and Vauxhall Cavalier were difficult to tell apart, even when they were on sale, if you removed their badges, largely because the same aerodynamic goals strongly influenced their designs.

-

13. Integrated headlights

All the early streamlined cars had headlights either fully or partly integrated into the bodywork, but this was also true of the resoundingly unaerodynamic 1934 Pierce-Arrow 840A (pictured).

The change from previously accepted practice was therefore at least partly a matter of styling, and it was largely completed in the 1940s, when some older motorists no doubt grumbled that cars now all looked the same as each other.

There were exceptions, though. The Citroën Traction Avant, Ford Popular and MG TD, for example, still had separate headlights in the 1950s, by which time they were looking very old-fashioned, while Citroën’s 2CV never lost them, despite remaining in production until the final decade of the 20th century.

-

14. Estate

Whether you call it estate, station wagon or shooting brake, this body style has one purpose – to provide as much room as possible for luggage behind the driver and passengers.

The best way of doing this is to extend the roof as far back as you can, and then add a rear window (the closer to vertical the better, in practical if not necessarily styling terms) at the last moment.

By the end of the Second World War, estate bodies were already familiar, having been used in, for example, the Buick Super (pictured) and Chrysler Town & Country, and of course they are still around today, though rapidly being superseded by SUVs.

Automotive design has changed tremendously in that period, but estates of any given era are all approximately the same shape at the rear, and you have to look for other styling cues to tell which is which.

-

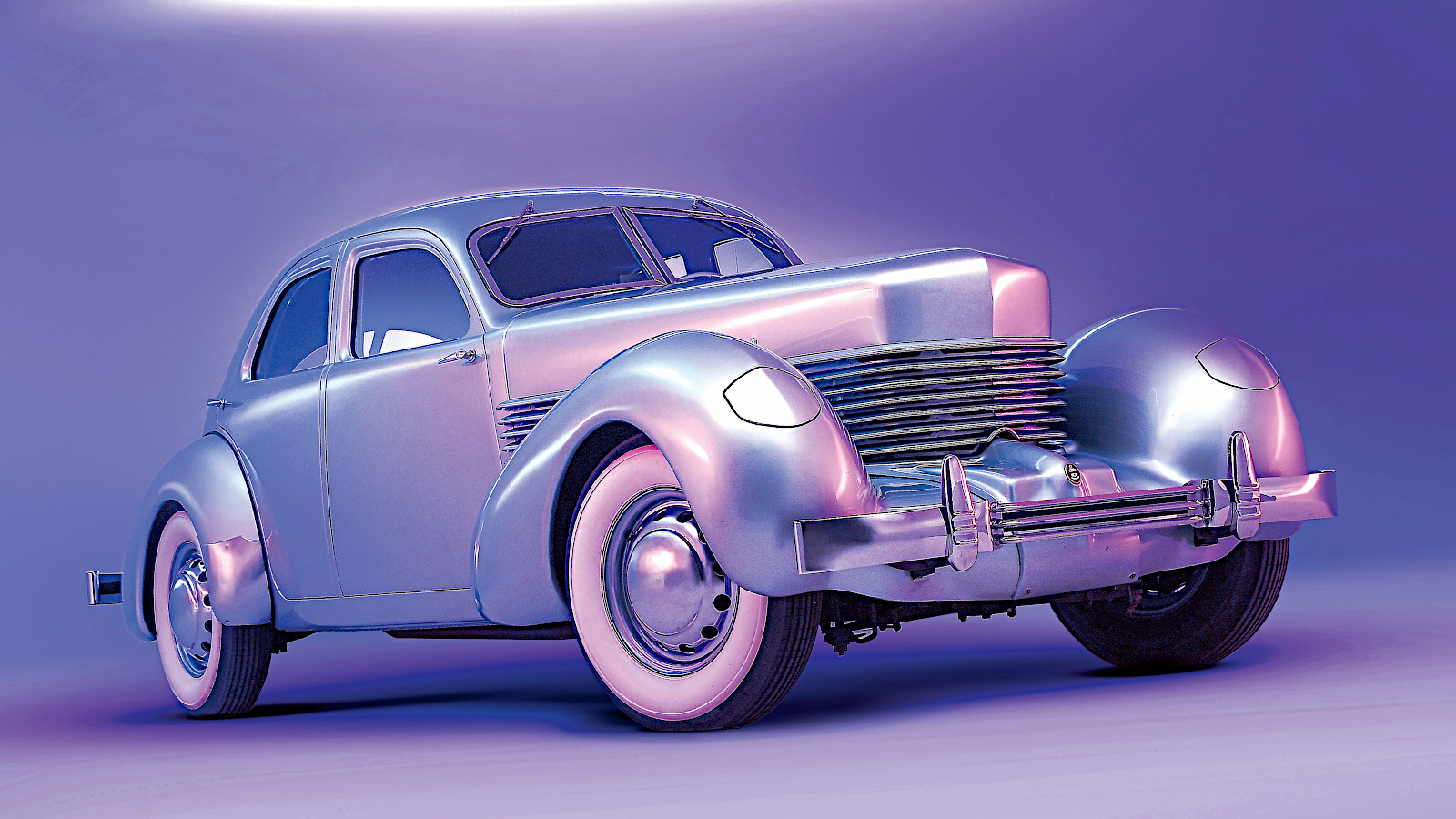

15. Hidden headlights

If the front end of a car is its face, the headlights are its eyes, but in the mid 1930s two manufacturers decided, with unusual and perhaps disturbing results, that they did not have to be clearly visible when not in use.

In the 402 and later models, Peugeot mounted them behind the radiator grille, while Cord concealed them completely within the front wings of its 810 (pictured), from which they emerged only when turned on.

Buick added concealed headlights to the Riviera for the 1965 model year, while pop-up lights became increasingly popular in sports cars, the Lotus Elan being an early example.

Pop-ups lights would later be used on sportier mainstream cars such as the Mazda 323F, Toyota Supra and Volvo 480.

-

16. Retractable hardtop

As well as having partially hidden headlights, the Peugeot 402 of the 1930s was, in Eclipse form, the first production car with a powered folding metal roof.

The idea didn’t catch on for a long time, but Ford helped to popularise it with the Fairlane 500 Skyliner produced in the late 1950s.

After that, interest grew gradually, and retractable hardtops became more common, though Audi was steadfast in refusing to use them on its convertible models.

In the first decade of the 21st century, retractable hardtop versions of what were normally produced as hatchbacks (now referred to as coupé-convertibles) enjoyed a brief vogue, examples including the Ford Focus CC, Nissan Micra C+C and Vauxhall Astra TwinTop.

-

17. Hatchback

Arguments have raged for years, and will probably continue to rage, about the identity of the first hatchback car.

There’s a case for saying it was the 11CV Commerciale version of the Citroën Traction Avant, but part of the problem is that even as late as 1965, when the Renault 16 (pictured) – indisputably a hatchback in the modern sense – was launched, no single word yet existed to describe a car with a tailgate functioning as an extra door at the rear.

Putting a label on something draws attention to it, and when the term hatchback was finally coined, the body style became dominant among family cars, at least in Europe if not in other parts of the world.

-

18. Ponton

Ponton is the word for a body style which looks old-fashioned now, but seemed radical when it was introduced, and remained popular for a very long time.

Ponton cars are three-box saloons with fully enveloping bodywork and, as might be unkindly said, slab sides lacking running boards.

The term is used unofficially for a series of Mercedes-Benz models including the 180 launched in 1953 (pictured), which looked almost unrecognisably different from its predecessors.

Although the name is rarely used to describe them, several small European rear-engined saloons of the 1960s with horizontal bootlids, such as the Hillman Imp, Renault 8 and Simca 1000, essentially have ponton bodies, whereas the Volkswagen Beetle, and Fiat 500 and 600, whose engine compartments are much curvier, arguably don’t.

-

19. Off-roader

The military 4x4s used by the US Army in the Second World War inspired several non-military versions which we’re describing here as off-roaders, rather than SUVs.

Like the civilian Jeeps introduced by Willys-Overland after peace returned, they are all notable for their ruggedness and simplistic body design, which tends to involve a lot of straight edges.

Toyota and, surprisingly, French luxury car manufacturer Delahaye, both put Jeep-like vehicles on sale in the 1950s, while the original Land-Rover (pictured), which didn’t look anything like a Jeep but was similar in concept, was launched in 1948.

In its final form as the Defender, the Land Rover lasted until 2016, and the Mercedes-Benz G-Class (originally the G-Wagen), a late starter with a launch date of 1979, is still with us, though in substantially developed form.

-

20. MPV

Multi-Purpose Vehicles, known as minivans in the US and colloquially as people carriers in the UK, eased gently into motoring history.

The first is reckoned to have been the Stout Scarab of the late 1930s, but this was never put into full-scale production, whereas the DKW Schnellaster, manufactured from 1949 to 1962, definitely was.

Among modern MPVs, the first were the closely related Dodge Caravan and Plymouth Voyager introduced in 1983 – and subsequently branded as Chrysler Voyager in Europe – and the following year’s Renault Espace (pictured), which had been developed by Matra.

Since the whole point of them is to provide as much interior space as possible, MPVs are usually large, boxy vehicles with short noses, though there are considerable differences in their design details.

-

21. Reverse-angle rear window

The first production car with a reverse-angle rear window appears to have been the 1958 Lincoln Continental.

The idea did not catch on in a big way, but enough manufacturers adopted it over the next few years for us to be able to describe it as a short-lived styling trend.

The more famous examples include Ford of Britain’s Consul Classic and last-generation Anglia (pictured), the Citroën Ami, the Reliant Regal and the Mazda Carol kei car.

A similar design was used for the Yaris-based WiLL Vi, built in 2000 and 2001 by Toyota, but not branded as such.

-

22. Bubble cars

Tiny roadgoing passenger vehicles have been known through the ages as cyclecars, microcars, quadricycles, voiturettes and, in a very specific Japanese case, kei cars.

The term bubble cars refers mostly to miniature machines of the 1950s and ’60s, whose designers opted for a round shape, no doubt in some cases to maximise interior space in a model which by its very nature couldn’t have very much of this.

The Isetta, initially conceived by Iso and later developed by BMW, is possibly the most recognisable of them, but the Heinkel Kabine (UK-built Trojan version pictured), and the Messerschmitt KR175 and KR200 are also well known.

The Peel Trident, built on the Isle of Man, is also quite bubbly, but the even smaller P50, sometimes referred to as a bubble car, isn’t.

-

23. Gullwing doors

The first and most celebrated production car with gullwing doors was the Mercedes-Benz 300SL coupé (pictured), produced from 1954 to 1957.

Mercedes returned to the idea when it developed the C111 concept cars around 1970, and later for the SLS AMG production car of 2010.

In general, gullwing doors have mostly been used for competition cars or concepts, but the small list of those on sale to the public includes the Bricklin SV-1, the De Lorean DMC-12 and the Wartburg-engined Melkus RS 1000 sports car produced in the then East Germany throughout the 1970s.

-

24. Tailfins

The golden age of tailfins lasted from approximately the mid 1950s to the early 1960s, a time when people were already familiar with aeroplanes and becoming accustomed to spacecraft.

The Cadillac Eldorado gives a good example of how fins progressed – small but noticeable in 1953, they became enormous in 1959 (as pictured here), but were very much reduced by 1963.

Tailfins were popularised in North America, but the trend was copied in Europe, for example on the Peugeot 404 and the various BMC Farina models.

-

25. Beach cars

Although some of them were originally intended for military uses, beach cars are better known for being suitable, not necessarily for actually being driven across sand, but certainly for use in coastal areas in warm climates.

None of them had structural roofs (flimsy upper coverings were available instead), and all were based on small and usually popular production cars.

For example, Ghia produced Jolly versions of the Renault 4 CV, Fiat 500 and, as pictured here, Fiat 600, while Vignale used the 500 as the basis for its Gamine.

From France, the Citroën Méhari and Renault Rodeo were based on the 2CV and R4 respectively, while the UK’s contribution to the genre was the Mini Moke.

-

26. Removable roof panels

Convertibles are all very well, but if you want to enjoy open-air motoring without radically altering the profile of the car you’re doing it in, removable roof panels are the way to go.

The arrangement is often known as a targa top, after Porsche introduced it in the 911 targa of 1966 with great success – in the early 1970s, 40% of all 911 sales were accounted for by these models.

However, Triumph got there first with the conceptually similar Surrey top, which was available on the TR4 (pictured) from 1961.

Some cars, famously including the third-generation Chevrolet Corvette, have been available with two removable roof panels, one each side of the centre line, a system usually referred to as a T-top.

-

27. Mid-engined sports cars

Although it had been tried decades before, mounting an engine between the passenger compartment and the rear wheels became a regular part of roadgoing sports-car design in the 1960s, not long after it had been adopted in Formula One.

The car known in its lifetime by several names, but now usually referred to as the Matra Djet (pictured), led the way, and was soon followed by the De Tomaso Vallelunga, the Lamborghini Miura and the Lotus Europa.

None of them looked anything like today’s supercars in detail, but the basics have not changed in 60 years.

Cars of this type are all low, they usually have space for only two seats (the McLaren F1 being one of the rare exceptions) and there is no need for long front or rear overhangs, though these may be used for aerodynamic or stylistic purposes.

-

28. Aerodynamic aids

Wind-guiding appendages became common in competition cars in the 1960s, and soon filtered through to roadgoing vehicles.

Two particularly eye-catching early examples were the Dodge Charger Daytona (pictured) and Plymouth Superbird – collectively known as the Winged Warriors and used as the basis for NASCAR racers – both of which had long, aerodynamic noses and extraordinarily large rear wings.

The purposes of those items were to smooth out the airflow and create downforce respectively.

They both worked well, but as the years went on, aerodynamic aids were increasingly fitted because they looked good rather than because they were effective, regardless of claims made by the car manufacturers.

-

29. SUVs

You may search in vain for agreement on the exact definition of a Sports Utility Vehicle, but broadly speaking they started out as off-roaders designed to be suitable for everyday road use.

Early Land-Rovers are not referred to as SUVs, but the original Range Rover (pictured) could be, even though the term wasn’t used when it first appeared.

Since then, SUVs have become outstandingly popular, to the point where they are being built by manufacturers as unadjacent to each other as Dacia and Rolls-Royce.

Regardless of size, cost, whether or not they have four-wheel drive, or any other consideration, they all share a few key attributes.

They have body shapes which give plenty of space for passengers and luggage, and ride heights which allow drivers to see further than they could in a lower-slung conventional car.

-

30. Crossovers

There was a time when every major motor show featured several crossovers which were either ready for production or soon would be.

The term suggests a cross between a regular car and an SUV, and replaced the earlier ‘lifestyle SUV’, which implied a vehicle that looked as if it might perform well off-road but usually didn’t.

The Simca 1100-based Matra Rancho of 1977 (pictured) and the slightly later AMC Eagle could both be described as early crossovers, though their designs were very different – the former was a rugged-looking vehicle with no off-road pretensions at all, while the latter had a much more conventional appearance combined with considerable ride height and four-wheel drive.

A more obvious ancestor of today’s crossovers is the first Toyota RAV4, which went on sale in 1994.