A very decent junior supercar, then? Indeed, but also one that fulfilled its creators’ self-imposed brief, to be a supercar that was easy for a novice to drive, docile around town and, as Spectre’s brochures suggested, ‘a super sportscar that is no more expensive to maintain than a family saloon’. The R42 required oil and filter changes every 12,000 miles, rather than monthly ministrations by an overpriced exotics expert.

There is, however, rather a large elephant in the room: price. At launch in 1995, the R42 was stickered at £69,950 – £18k ahead of an Esprit S4S, £1705 more than an NSX and £1500 costlier than a Porsche 964 RS. And with the R42 taking more than 2000 man-hours to build, £70k wasn’t enough to stop Spectre losing money.

In that price bracket, even Lotus knew that well-heeled buyers didn’t want to see comedy glassfibre matting in the fuel-filler flap, ripples in the roof, nor Fiesta keys – still with Ford badges – and wipers that lifted off the ’screen at 95mph.

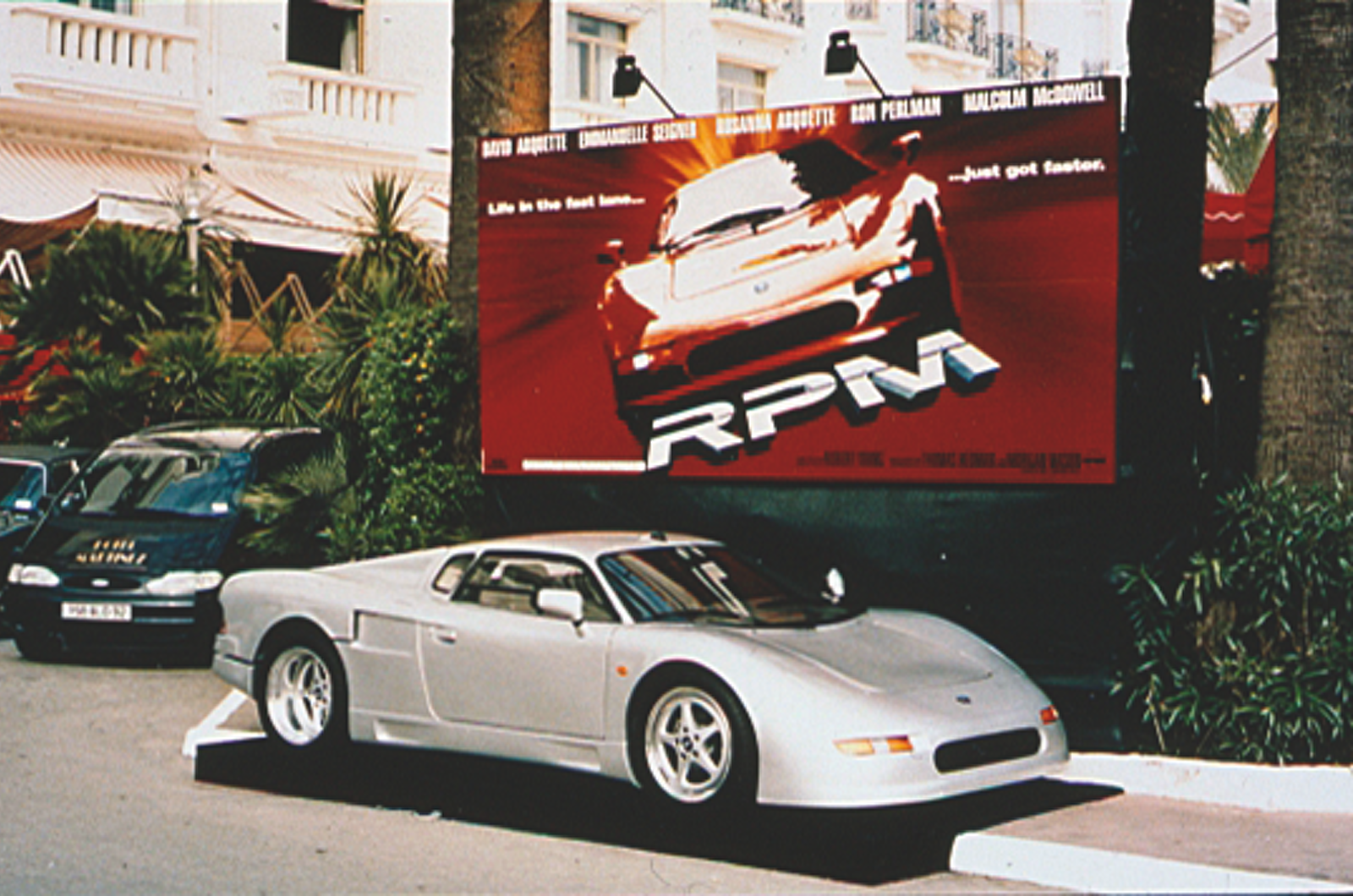

Spectre Supersports returned to the drawing board and came up with the R45, a higher-tech, easier to assemble and better-quality product that, crucially, could be sold at a higher (£90,000) price.

Spectre Supersports returned to the drawing board and came up with the R45, a higher-tech, easier to assemble and better-quality product that, crucially, could be sold at a higher (£90,000) price.

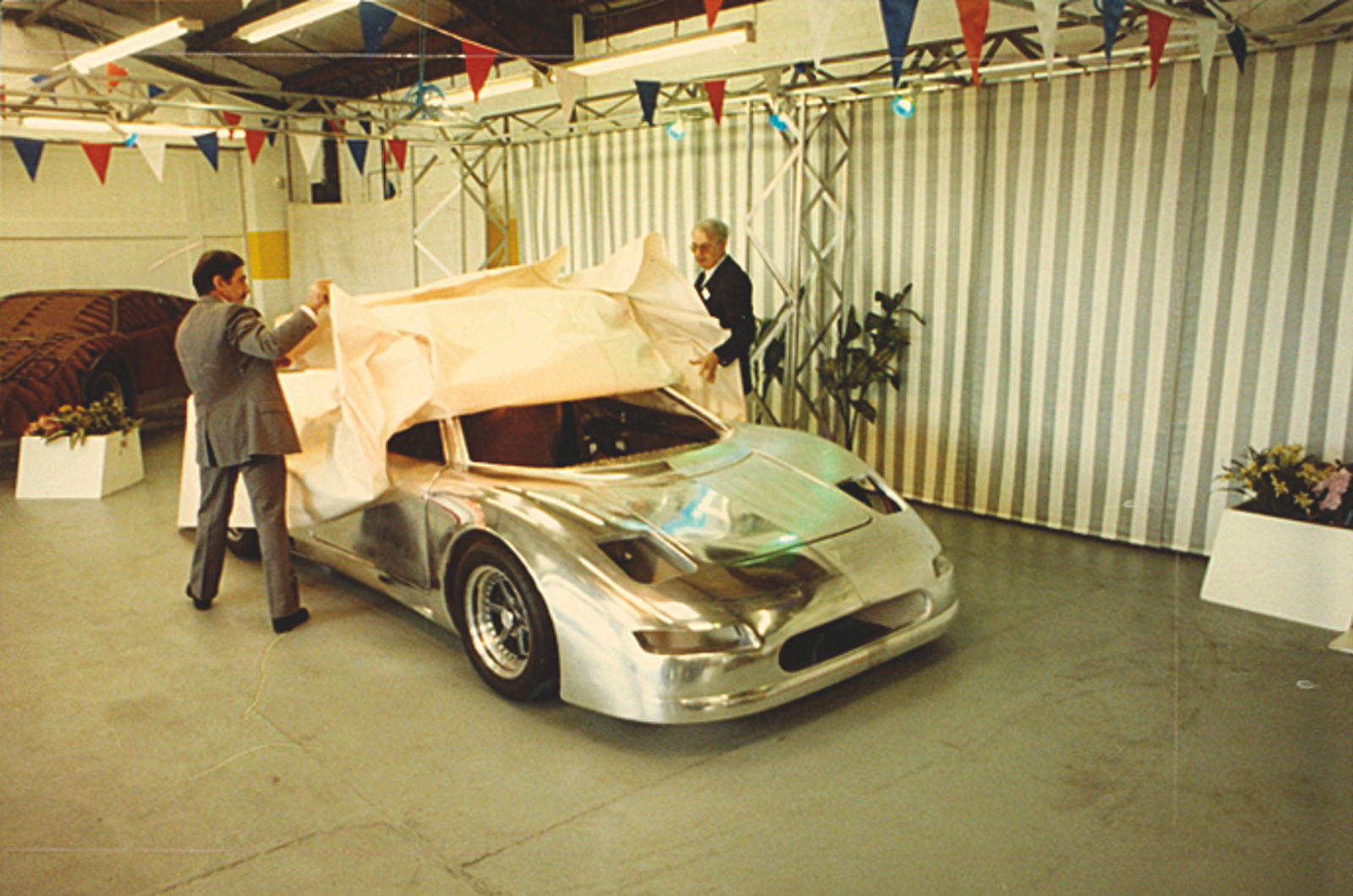

The R45 was unveiled by Desmond Llewellyn – better known as James Bond’s gadget expert Q – at the London Motor Show in October 1997, but the writing was on the wall. The Spectre coffers were empty and, with just two R45 prototypes completed, the firm went into receivership before the year was out.

The Spectre R42 came close to greatness

In 1997, you’d need to have really fallen for the Spectre to put up with its many and varied flaws. But it’s not 1997, it’s 2019. And, if you can find one, prices are now likely to be far more reasonable: one sold with H&H Classics in 2016 for £26,320.

Without a badge in sight the Spectre seems almost ashamed of its origins, yet there is no shame in coming so close to greatness. Today, the R42’s rarity and ability make it a more intriguing prospect than the cars it struggled to match when it was new.

Images: Malcolm Griffiths

SPECTRE R42 FACTFILE

- Sold/number built 1994-‘98/23

- Construction honeycomb-reinforced folded aluminium sheet monocoque with glassfibre body, steel roll-over bar and steel subframes

- Engine mid-mounted, all-alloy 32v quad-cam 4603cc 90˚ V8, with electronic fuel injection

- Max power 350bhp @ 5900rpm

- Max torque 335lb ft @ 4850rpm

- Transmission rear-mounted Getrag five-speed transaxle (optional six-speed), driving rear wheels

- Suspension independent, at front by double wishbones, swivel joints, adjustable anti-roll bar rear inverted wishbones, parallel radius rods, anti-roll bar; rising-rate coil springs and adjustable Spax gas telescopic dampers f/r

- Steering power-assisted rack and pinion

- Brakes 111/2in (295mm) ventilated discs, with servo

- Wheels/tyres 17in alloys, 235/45 ZR17 (f), 335/35 ZR17 (r) tyres

- Length 13ft 6in (4115mm) Width 6ft 1in (1854mm) Height 3ft 7in (1092mm) Wheelbase 8ft 2in (2489mm) Weight 3417lb (1550kg)

- 0-60mph 4 secs

- Top speed 175mph

- Mpg 14

- Price new £74,950 (1997)

READ MORE

How the Lola Mk6 annoyed Ford bosses and inspired the GT40

Why the Bristol Fighter is a supercar with a difference

Ford's Ferrari beaters

Why this charming Moretti 2300S leaves us wanting more

Alastair Clements

Alastair is Editor in Chief of Classic & Sports Car and has been associated with the brand for more than 20 years

Car described the R42 as ‘an example of how difficult it is to play Ferrari and Lamborghini’s game without players like Pininfarina and Gandini’, but perhaps that’s a little harsh.

Car described the R42 as ‘an example of how difficult it is to play Ferrari and Lamborghini’s game without players like Pininfarina and Gandini’, but perhaps that’s a little harsh.

The Blue Oval theme continues inside. It’s clear that several cows, a couple of Walnut trees and a circa 1994 Ford Fiesta gave up their lives to furnish what Spectre called its ‘Racing car in a dinner jacket’.

The Blue Oval theme continues inside. It’s clear that several cows, a couple of Walnut trees and a circa 1994 Ford Fiesta gave up their lives to furnish what Spectre called its ‘Racing car in a dinner jacket’.

First up, the R42 is unusual for its genre in that it doesn’t intimidate. The clutch is a bit heavy, but that knuckle-cracking gearchange is amazingly light considering the torque going through it and the gate – borrowed from the Lotus Esprit – is well defined for a cable set-up, probably due to the quality of the Getrag transaxle (developed for Audi).

First up, the R42 is unusual for its genre in that it doesn’t intimidate. The clutch is a bit heavy, but that knuckle-cracking gearchange is amazingly light considering the torque going through it and the gate – borrowed from the Lotus Esprit – is well defined for a cable set-up, probably due to the quality of the Getrag transaxle (developed for Audi).

Spectre Supersports returned to the drawing board and came up with the R45, a higher-tech, easier to assemble and better-quality product that, crucially, could be sold at a higher (£90,000) price.

Spectre Supersports returned to the drawing board and came up with the R45, a higher-tech, easier to assemble and better-quality product that, crucially, could be sold at a higher (£90,000) price.