First away was DePalma’s Ballot alongside the sluggish Émile Mathis, while down the grid patriotic blues contrasted with the dashing white American machines.

Chassagne in ‘our’ car and Albert Guyot’s Duesenberg were second and third away, followed by Jimmy Murphy – his torso strapped because of injury in a practice shunt avoiding a horse – and young Henry Segrave’s Talbot.

The Duesenbergs set a lightning pace from the moment Commission Sportive Internationale president Chevalier René de Knyff dropped the flag, and by the second lap Murphy had taken the lead with teammate Joe Boyer in second.

The Ballots were chasing hard, headed by Chassagne and a downbeat DePalma. The leading Duesenberg’s speed was mighty, as Murphy set a 7mins 46 secs lap, but his pitstop to change rear tyres dropped him behind Chassagne, the quickest Ballot setting a strong pace.

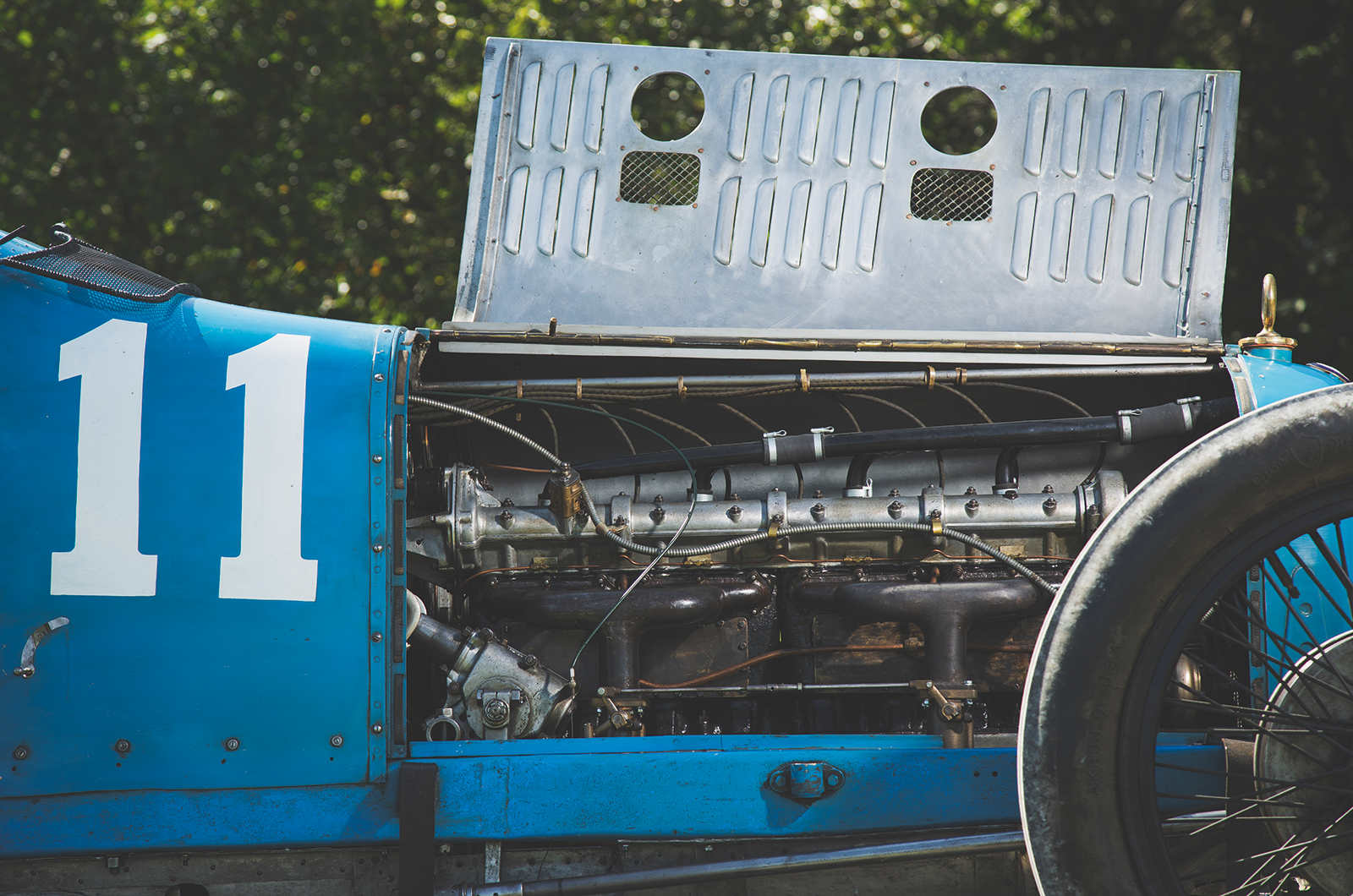

Powering along in this evocative racer

The French team had chosen straight-sided Pirelli tyres, which ran the full distance without problems, while others lost time with pitstops.

With a French car and driver now out in front, the huge crowd was greatly relieved and cheered Chassagne around the sandy course, while down in sixth DePalma struggled with carburettor problems and lost 5 mins to his teammate.

By half distance all French hopes were focused on Chassagne in car number eight, the tension mounting when Murphy regained the lead only to drop back after more pitstops to leave Boyer giving chase.

With each lap the lead varied between 19 and 30 secs, as Boyer pushed harder to catch the leading Ballot, but with every advantage gained Chassagne responded.

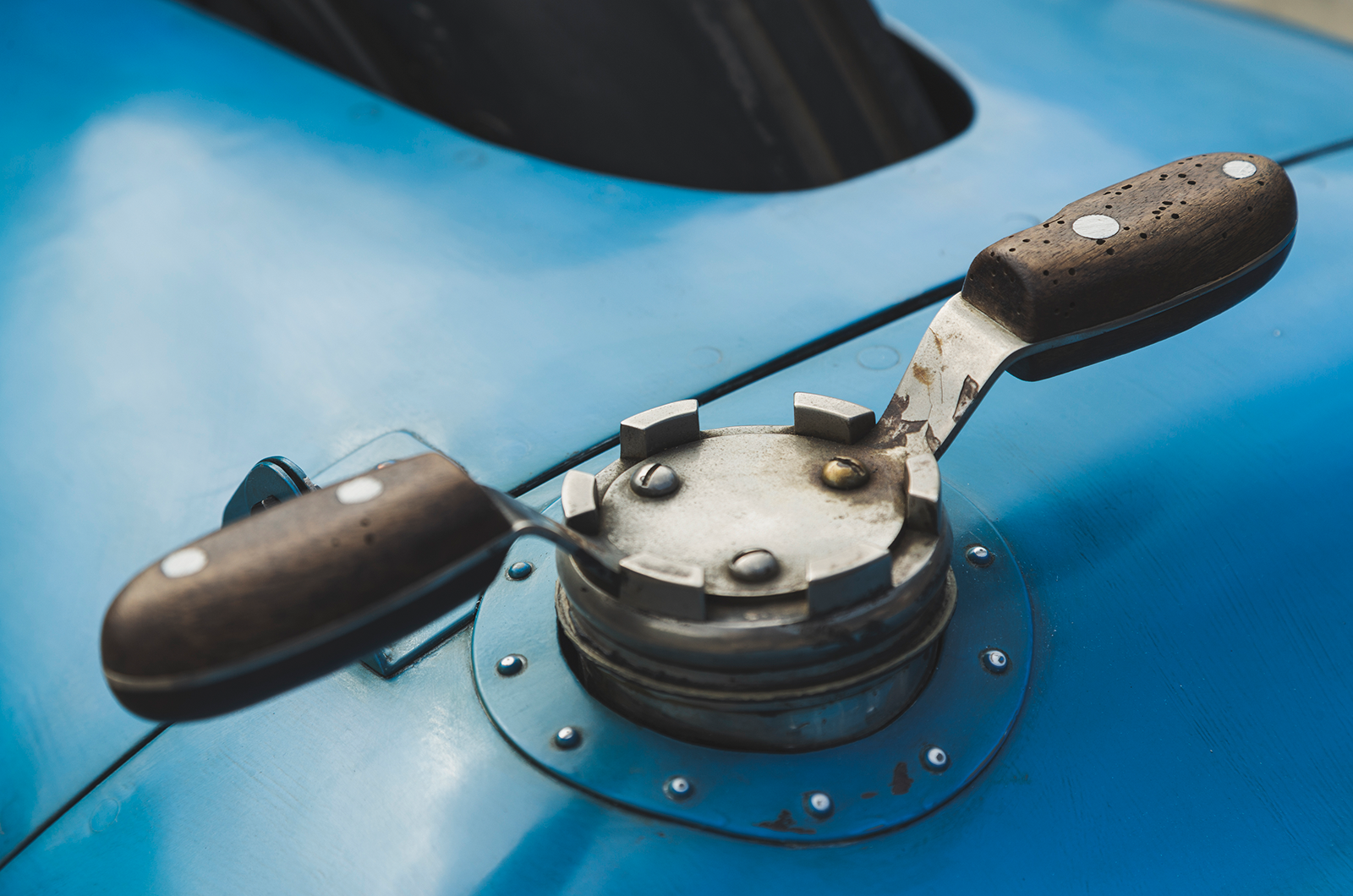

The ‘EB’ badge shows early nautical links

Then, on lap 18, a deep sigh was heard all along the packed pit straight as the leading Ballot slowed into its box with petrol pouring from beneath the car.

After the high-speed pounding, the tank mounts had fractured and dropped it on to the driveshaft, creating a hole and rapid fuel loss.

The crowd was stunned that the Ballot was out when the news came through that Boyer had also stopped with a broken engine.

With 12 laps to go, Murphy found himself back in the lead with teammate Guyot close behind. Ballot’s hopes rested only with DePalma, by then 8 mins further back behind the Duesenbergs.

The winged fuel cap saved time

As Murphy set a regular pace at the front, the drama played out behind in the chasing pack.

Guyot was now plagued with tyre problems, made worse when a piece of flying rubber knocked his riding mechanic unconscious.

Once back in the pits, the stunned passenger was lifted out and a team supporter, still in casual clothes and without protective goggles, stepped in for the remainder of the race.

The shocking state of the track was best highlighted by an incident with Segrave’s car. As the frustrated Talbot pit crew resorted to borrowing tyres from rival teams, the valiant young Englishman battled on.

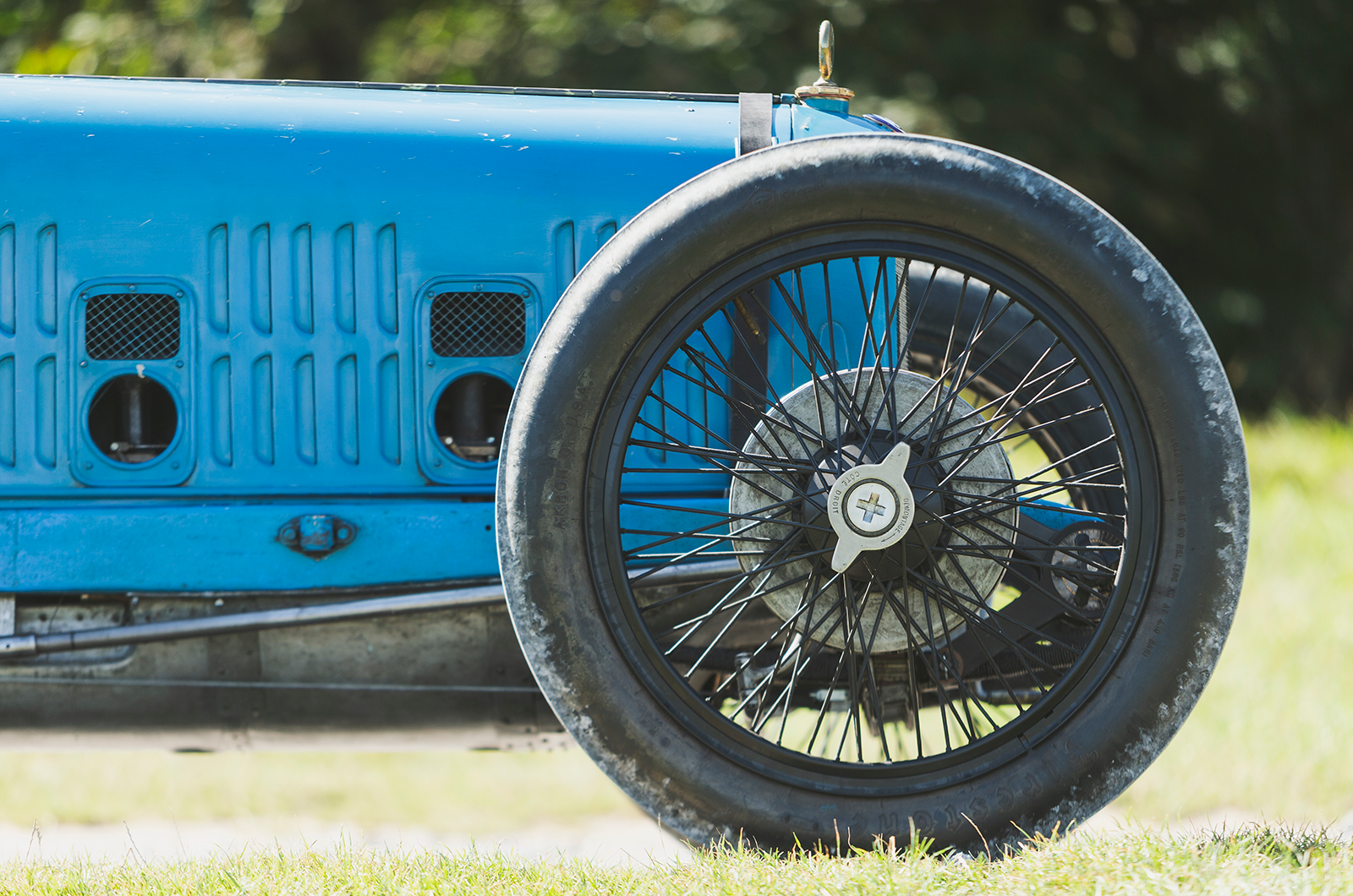

Exquisite details, perfectly preserved

When leader Murphy roared past, the Duesenberg’s rear wheels spattered the Talbot with more stones.

One large rock bounced off the scuttle and ricocheted off his mechanic Jules Moriceau’s forehead, gashing his temple and knocking him out.

Segrave motored on, determined to finish, for five miles unaware of his mechanic’s unconscious state.

Only when he next pitted and the roused Moriceau wiped his face of blood did Segrave discover the plight of the plucky Frenchman, who insisted they continue.

“You call this bunk a road race,” exclaimed charismatic Duesenberg ace Boyer, who had retired with a broken conrod. “I call it a damn rock-hewing contest!”

The distinctive body is in France’s racing blue

Amazingly, by two-thirds distance 10 cars were still running and the crowd was gripped by the drama.

The pits were continually full of incident, with repairs and tyre changes, but the leaderboard showed the American team well clear – Murphy leading teammate Guyot, with DePalma in the Ballot more than 14 mins behind in third.

Just as everyone thought the result was set, Murphy’s Duesenberg arrived in the pits on the penultimate lap with a flat tyre and a dry radiator after a rock had smashed the core.

The American team had chosen not to carry a spare because Murphy maintained it was safer to limp back than to attempt to change a tyre on the course, not to mention the weight saving.

A nearly century-old view

The Ballot team’s hopes were briefly raised by DePalma running fastest of all, but his challenge came too late.

On the final lap, Murphy nursed his boiling Duesenberg home, 3 mins slower than his previous pace.

At the flag he was still 15 mins clear of DePalma, with Goux’s 2-litre, four-cylinder Ballot finishing an impressive third.

Segrave, after changing tyres 14 times through his five-hour endurance run, finished ninth and last, an hour after winner Murphy.

A rough Le Mans in 1921 brought defeat to Ballot

The disappointed spectators didn’t applaud Murphy and showed little emotion for the US hero’s remarkable performance.

No national anthem was played and that evening the first toast was for Goux in third. Not until the awards dinner in Paris were the Duesenbergs honoured.

As reports were transmitted around the world about the great American victory, none showed less sporting spirit than Ernest Ballot, who in the evening related to a crowd how his team was cheated.

Story has it a soapbox was provided and in the Le Mans main square he ranted to listeners, proclaiming that the American cars had been reduced to junk while his racers were ready to start another 30 laps. “Let’s do it again,” Ballot bellowed, “and we’ll see who wins.”

Ballot scored a 1-2 at the 1921 Italian Grand Prix

Later in the year the 3-litre Ballots would finally win a major event, the first Italian Grand Prix, with a 1-2 over the Fiat 802 team around the fast Brescia road course.

After a third place at the 1922 Indianapolis 500, the three magnificent Grand Prix cars became redundant as Ballot focused on producing a new sports car, the fabulous twin-cam 2LS.

The GP cars were sold off to privateers, with chassis 1006 coming to England to become a regular at Brooklands in the hands of Campbell, ‘Bentley Boy’ Jack Dunfee and Australian racer Joan Richmond.

With the formation of the Vintage Sports-Car Club, the Ballot was preserved by a succession of eminent enthusiasts including Cecil Clutton and Humphrey Milling.

Walsh savours the experience from behind the Ballot’s wheel

The 3/8 was little seen in recent decades before Schaufler brought it out of hiding and refreshed it for selected outings.

His dream is to demonstrate the Ballot at the centenary of the Italian Grand Prix: driving the vintage straight-eight around Monza cheered on by the tifosi will be a huge moment.

A reunion with the winning Duesenberg from the Indy museum at the Le Mans Classic would perhaps be more appropriate, but for me a run in the legendary Ballot around a dusty, deserted country estate is as good as it gets.

Images: Luc Lacey

Ballot, by Daniel Cabart and Gautam Sen, is priced at $350 from Dalton Watson

READ MORE

Original is best: ex-King Leopold Bugatti Type 59

Keeping the faith: restoring a Duesenberg Model SJ

Tourer de force: Maserati Tipo 26

Mick Walsh

Mick Walsh is Classic & Sports Car’s International Editor