Turbo engines, with onboard diagnostics and individual coil packs for each cylinder, were made available to Rolls-Royce customers in the Flying Spur and the end was in sight for the non-turbo L-series, the last of them being fitted to the short-lived Silver Dawn version of the SZ in 1997.

The extent of the personalisation options in the 2020 Mulsanne is incredible

As much as 408bhp was now quoted for the Continental T with its water-cooled turbo, but a light-pressure version, at 300bhp, was fitted to the niche 1997-’98 Bentley Brooklands S and R, and the 1997-2000 Rolls-Royce Silver Spur.

The decision by parent company Vickers to move engine production from Crewe to Cosworth in Northampton in 1996 looked like the endgame for the L-series, which by that stage was only used in the Continental and the Azure, having been replaced in the latest four-door cars by BMW-sourced V8s and V12s.

Sadly, the Bentley and Rolls-Royce marques were pulled apart by the various intrigues surrounding the Vickers deal.

But whatever you might think about selling off the two most famous names in British motoring to foreign multinationals, one of the happier outcomes was VW’s decision to continue with the old V8 in its most importantly revised form yet for the Arnage R and T, the latter marketed as the fastest four-door car in the world from 2007 with the twin-turbocharged 500bhp incarnation of the L-series, for which it even claimed better fuel consumption.

The evocative ‘Flying B’ survives to this day

A 530bhp version of this engine was developed for the 2008-’11 Brooklands coupé, a low-volume flagship model replacing the Continental Rand T.

At the time it had the highest torque value of any production petrol engine yet built for road use.

The final VW-era Mulsannes were available in standard form, with a mere 500bhp, or as the 530bhp Mulsanne Speed.

At the very top of the range is the extended-wheelbase model, a 180mph-plus tycoon’s office on wheels.

None of these are to be confused with the W12 and V8-engined Continental GTs or the new twin-turbo 6-litre W12 Flying Spur that effectively replaces the handbuilt Mulsanne.

This tech-heavy cabin is impressive, but not our Buckley’s natural environment

In profile, the Mulsanne is as handsome as you could reasonably expect a 21st-century super-luxury saloon to be in a world where such cars are built to impress oligarchs and billionaires rather than the likes of you and me.

It is faultlessly detailed and finished inside, where the customer is encouraged to customise the cabin to his or her taste – or lack of it.

Among the options are scatter cushions, illuminated tread plates and some horrifying marquetry possibilities, should you feel the need to embellish the flawless veneers in your £239,000 limousine with the sort of imagery normally reserved for the menu in a takeaway restaurant.

This near-190mph, aluminium-bodied, eight-speed behemoth looks as if it should weigh more than its 6000lb and certainly makes light of it.

In many ways, the V8 has been developed to a level of refinement and organ rearranging acceleration that buyers of the latest Teslas take for granted.

That anything so large should move so fast seems almost wrong: time and distance are compressed, the aim being to transmit the occupants – suitably entertained by the Wi-Fi and infotainment systems –seamlessly between climate-controlled environments.

The Mulsanne ‘face’ echoes that of the S2, without appearing to be a pastiche

It is a superb technical achievement, built for a different world than the one the S2 inhabited in 1959.

In those days, the difference between a £600 family car and a £5000 Bentley was huge; today, even the least-expensive cars are so fast, safe and capable that all the modern supersaloon can do is add size, ostentation, extra refinement and endless gadgets to soothe your progress.

Though dwarfed by the Mulsanne, the suavely elegant S-type has more presence. It is built on a more human scale in context with its surroundings, conveying benevolent nobility rather than brutish arrogance.

Inside, electric windows are its only nod to decadence but it smells wonderful and feels as welcoming as a favourite armchair.

In general terms it is still a quick, quiet car in which long distances can be covered with minimal effort, but to compare this Edwardian locomotive with its 2020 equivalent is neither fair nor particularly relevant.

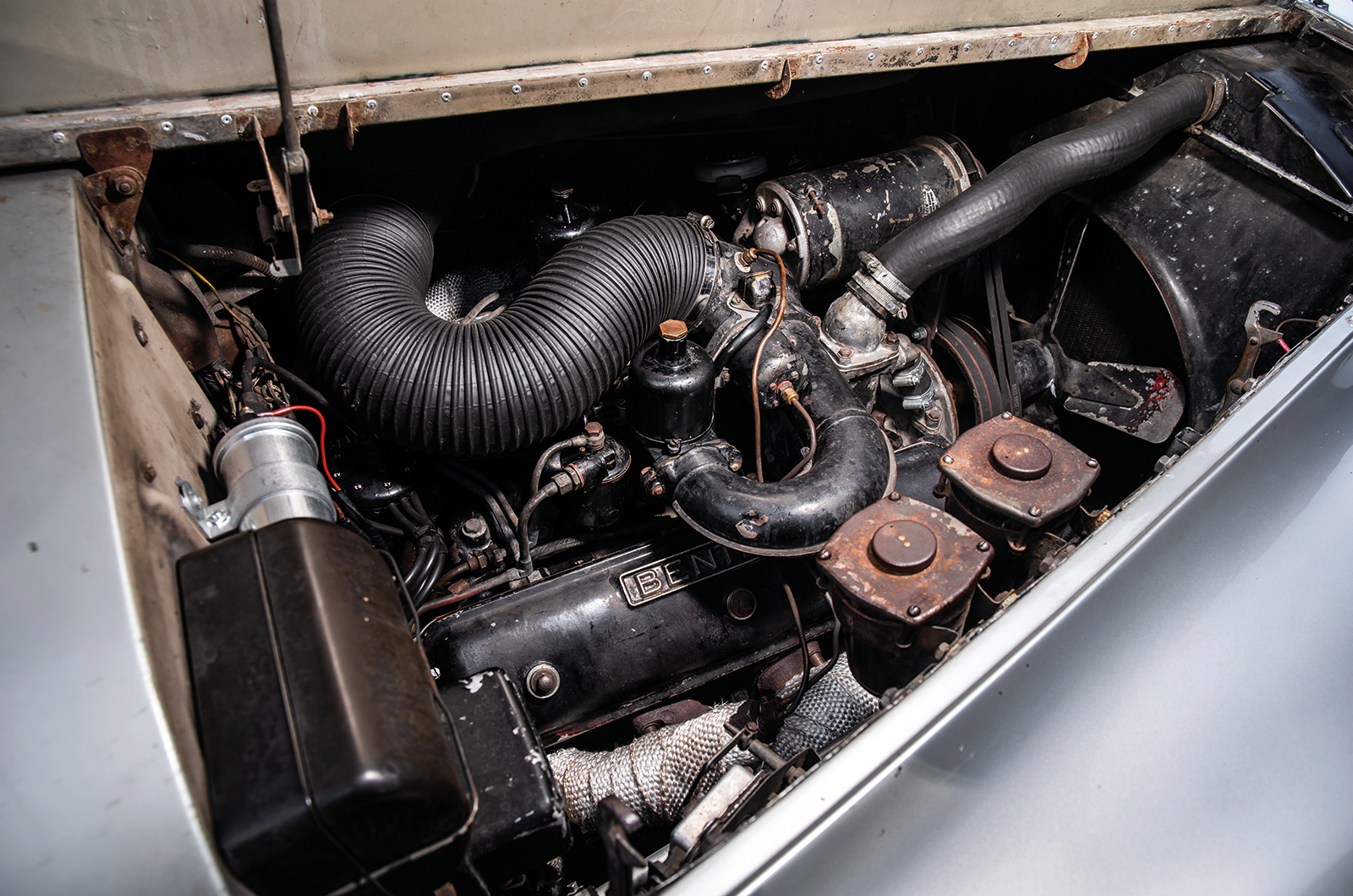

The long-serving L-series V8 was and is a massive technical achievement

Let’s just celebrate the resilience of this greatest of all ‘survivor’ engines.

With its neat plastic covers it looks very different today to the 1959 edition, whose shiny black enamelled finishes link it to its six-cylinder predecessor and even the Merlin V12.

I’d be surprised if they have even a single washer in common, but it is the continuity of development that counts.

And consider this: despite a 200% increase in power, the 2020 Mulsanne V8 still has the same bearing surface area specified by Rolls-Royce engineering chief Harry Grylls, while meeting emissions requirements that are 1000 times more stringent than they were in 1959.

Images: Luc Lacey/Jonathan Fleetwood

READ MORE

The conundrum of this unique Pinin Farina Rolls-Royce

Don’t buy that, buy this: Rolls-Royce Corniche vs Mercedes-Benz 280SE 3.5 Coupé

Bentley R-type Continental vs Continental R

Martin Buckley

Senior Contributor, Classic & Sports Car