Other than poor vision around those massive pillars it is an easy drive and feels immensely rigid, although there are quite a lot of groans and squeaks from the carbonfibre tub to suggest otherwise.

The muscle-car rumble from the side pipes grabs your attention at once.

With Drive engaged you don’t really think about the gearbox again, but the squishy brake-pedal feel – or lack thereof – seems immediately out of place, even if its epic ability to bring the SLR McLaren to a halt is never in question.

You get used to them, as you do the steering, which has a similarly once-removed Mogadon feel about it.

The SLR, with its 50:50 weight distribution, is very stable but also goes where it is bidden unfalteringly. Yet there is something simulated about what the steering wheel is telling you through your palms and fingertips.

Mercedes’ SLR McLaren weighs in at 3890lb (1768kg)

If the SLR McLaren has limits way beyond most drivers’ requirements (or nerve), it lacks clear signposts when you start to look for them.

Much is forgiven when you explore the straight-line performance. You suddenly have the sort of overtaking opportunities normally reserved for riders of big modern superbikes and you think twice before dipping into the last few millimetres of throttle travel.

Here, madness lives. With the blower spooled up and whining the thrust is as breathtaking as the noise, like a bandsaw cutting through logs.

And just as you think the rate of acceleration cannot get any more aggressive, the pull gets harder. It is exhausting, but you could get to like it.

The Bristol’s references to its past are more subtle than the Mercedes’ gills and exhaust pipes

The Fighter, to borrow estate agent patois, is more ‘approachable’ in every respect. The all-round vision, the ‘normal’ driving position and the airy sense of space inside its cockpit immediately put you at ease.

The interior is restrained with no contrivances – even the aircraft-style instruments above the windscreen and the cut-out drop glasses in the doors feel true to what the Fighter is all about.

The car is an exercise in soundly conceived suspension geometry, honest aerodynamics and balanced weight distribution carefully aligned with all the benefits of a giant engine and tall gearing in a strong, light, compact entity.

You can motor quietly through the Bristol’s six gears, which are largely optional in any case such is the massive torque, and enjoy the views through that wraparound windscreen.

The vast glass areas help form a crisp, evocative shape reminiscent of ’50s GTs

Dial up some chilled air and note that the dropped, serrated spokes of the pleasingly chunky steering wheel recall the aircraft-inspired helm fitted to the 1950s cars.

It is connected to a powered rack that never expects you to second-guess cornering set-ups. The nimble Fighter turns in beautifully, flatters your judgements and rewards your attention without requiring total concentration all the time.

At cruising speeds the aerodynamics cause the car to double down on the feeling of stability that pervades it at all times, without recourse to silly gadgets such as the SLR’s ‘airbrake’ that pops up out of nowhere in your rear-view mirror.

The Fighter’s nose doesn’t dive under braking, the tail doesn’t squat under acceleration. All your physical inputs are of equal weight, a heft appropriate to the job in hand.

‘The Fighter’s gearchange moves neatly through its gate as you explore the performance, fully comparable with the SLR but much less frantic’

The gearchange moves neatly and precisely through its gate as you explore the performance, fully comparable with the SLR but a much less frantic experience.

With a smooth rumble, then a muted howl, the V10 merely summons a flow of acceleration that is primal, a velvet shove into the middle distance riding a sublime bow-wave of torque.

You can’t imagine wanting much more urge but apparently some customers did: there was an ‘S’ version of the Fighter with 628bhp and a ‘T’ (turbo) with an alleged 1000bhp, although none of the latter were ever completed.

The wide dihedral-doored Mercedes dwarfs the gullwing-doored Bristol

Many more extreme statements of early 21st-century motoring excess have emerged since the Mercedes-Benz SLR McLaren died in 2009, but everything about it, from its £330,000 price-tag to the fact that a change of plugs will reportedly cost you £15,000, still seems marvellously over the top.

To drive one is an event; to own one, I suspect, a burden. It is exciting but not satisfying; dramatic to behold but not beautiful. It is not even all that rare.

It was a committee design rather than the vision of one man and his team, created in an atmosphere of competing tensions between the commercial instincts of Stuttgart and the purist sensibilities in Woking that was never going to result in an entirely happy car.

The Fighter, meanwhile, is much easier to warm to.

The Bristol wins the battle for our Buckley

As the first Bristol to dispense with the BMW chassis concept the Fighter was, in a sense, only the second truly all-new car Filton had ever produced. Everything else was an extrapolation of the 1947 400.

As well as being a radical departure from the firm’s traditional Chrysler V8-engined saloons, the Fighter was also much more than just another hopeful British specialist ‘comeback car’ of over-reaching ambitions and doubtful merit.

Here was a vehicle true to a firm’s traditions that, had it been conceived 10 years earlier, might have achieved the critical mass required to keep Bristol Cars alive.

There was science and substance behind the Fighter, but not enough money or marketing. It was too radical to appeal to existing Bristol customers, its message too subtle to get attention amid the lurid excesses of the 21st-century supercar landscape.

Images: Luc Lacey

Thanks to SLJ Hackett; Cotswold Classic Car Restorations

Factfiles

Mercedes-Benz SLR McLaren

- Sold/number built 2003-’09/2282

- Construction carbonfibre composite monocoque with carbon composite crash structures and aluminium subframes

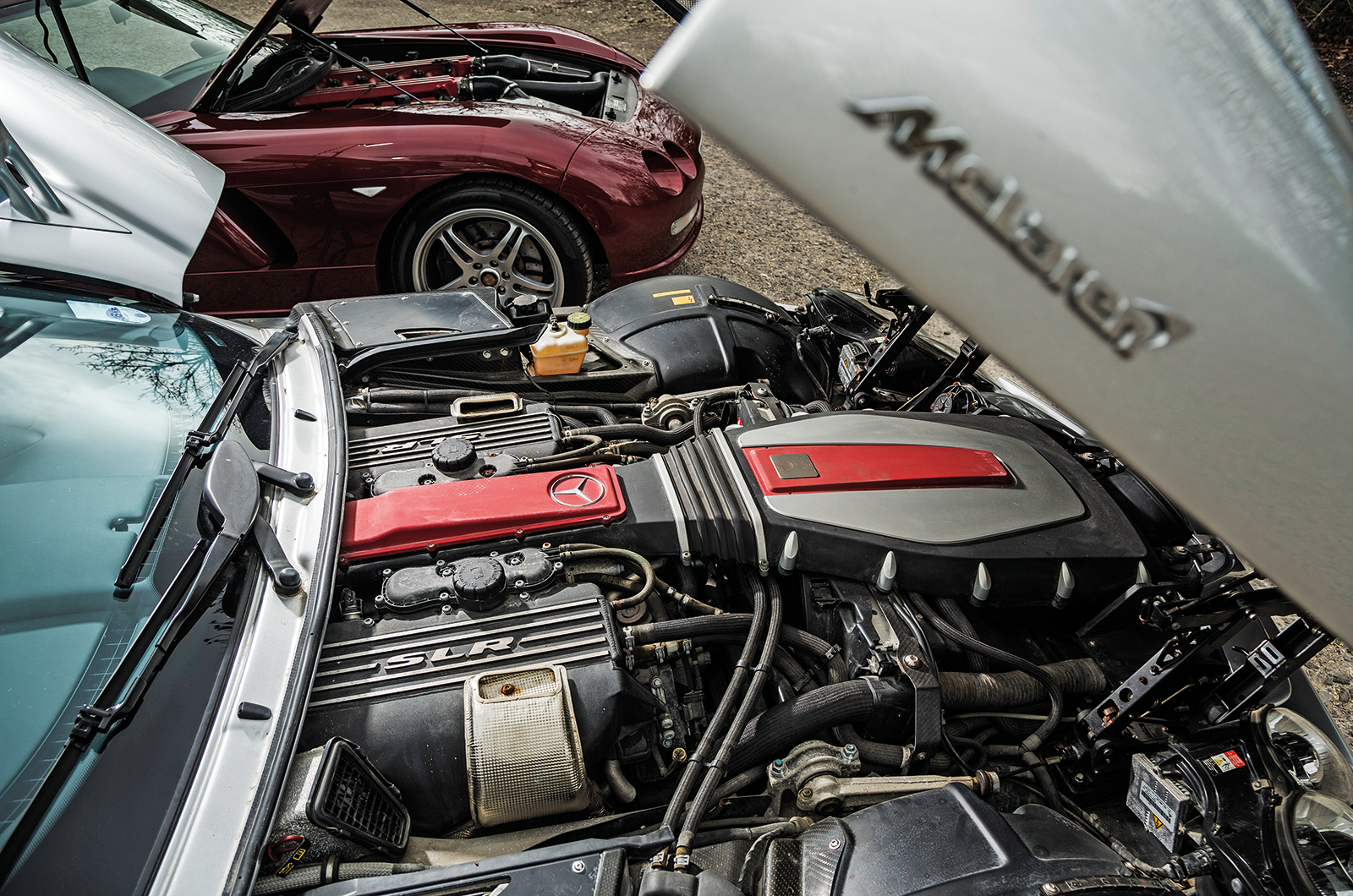

- Engine all-alloy, sohc-per-bank 5439cc V8, with screw-type supercharger and air/water intercooler

- Max power 626bhp @ 6500rpm

- Max torque 575lb ft @ 3250-5000rpm

- Transmission five-speed automatic, RWD

- Suspension independent, by double wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers; front anti-roll bar

- Steering power-assisted rack and pinion

- Brakes electro-hydraulic carbon-ceramic discs with anti-lock and brake assist; computer-controlled airbrake

- Length 15ft 3¼in (4656mm)

- Width 6ft 3in (1905mm)

- Height 4ft 1¾in (1261mm)

- Wheelbase 8ft 10¼in (2700mm)

- Weight 3890lb (1768kg)

- 0-60mph 3.8 secs

- Top speed 207mph

- Mpg 19.5

- Price new £330,000

- Price now £2-250,000*

Bristol Fighter

- Sold/number built 2004-’11/c11

- Construction steel box-section chassis with integral front bulkhead and rollover protection, carbonfibre/aluminium body

- Engine all-alloy, ohv 7990cc V10, with multi-point fuel injection

- Max power 525bhp @ 5500rpm (550bhp at speed due to ram-air effect)

- Max torque 525lb ft @ 4200rpm

- Transmission six-speed manual, RWD

- Suspension independent, by double wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar f/r

- Steering power-assisted rack and pinion

- Brakes ventilated discs, with servo and anti-lock

- Length 14ft 6in (4420mm)

- Width 5ft 9¾in (1795mm)

- Height 4ft 5in (1346mm)

- Wheelbase 9ft ¼in (2750mm)

- Weight 3527lb (1600kg)

- 0-60mph 4 secs

- Top speed 210mph

- Mpg 21.5

- Price new £229,125 (2006)

- Price now £2-300,000*

*Prices correct at date of original publication

READ MORE

Behind the scenes of the last days at Bristol Cars

Transatlantic hybrids: Bristol 407, Jensen C-V8 and Gordon-Keeble GK1

Unique McLaren F1 could top $15m

Mercedes-Benz 450SLC 5.0: the world’s least likely rally car?

Martin Buckley

Senior Contributor, Classic & Sports Car