It had been a Grand Prix season dominated by tragedy, controversy and bitter feuding.

First, the drivers had gone on strike. Then some of the teams did. Gilles Villeneuve and Riccardo Paletti had been killed in accidents, and the cars had become not only dangerously fast, but punishing and unrewarding to drive.

At the end of 1982, the FIA therefore stepped in and banned ground-effect technology. With only a few months until the opening race of ’83, teams may have been caught on the hop, but few argued that it was anything other than the right thing to do.

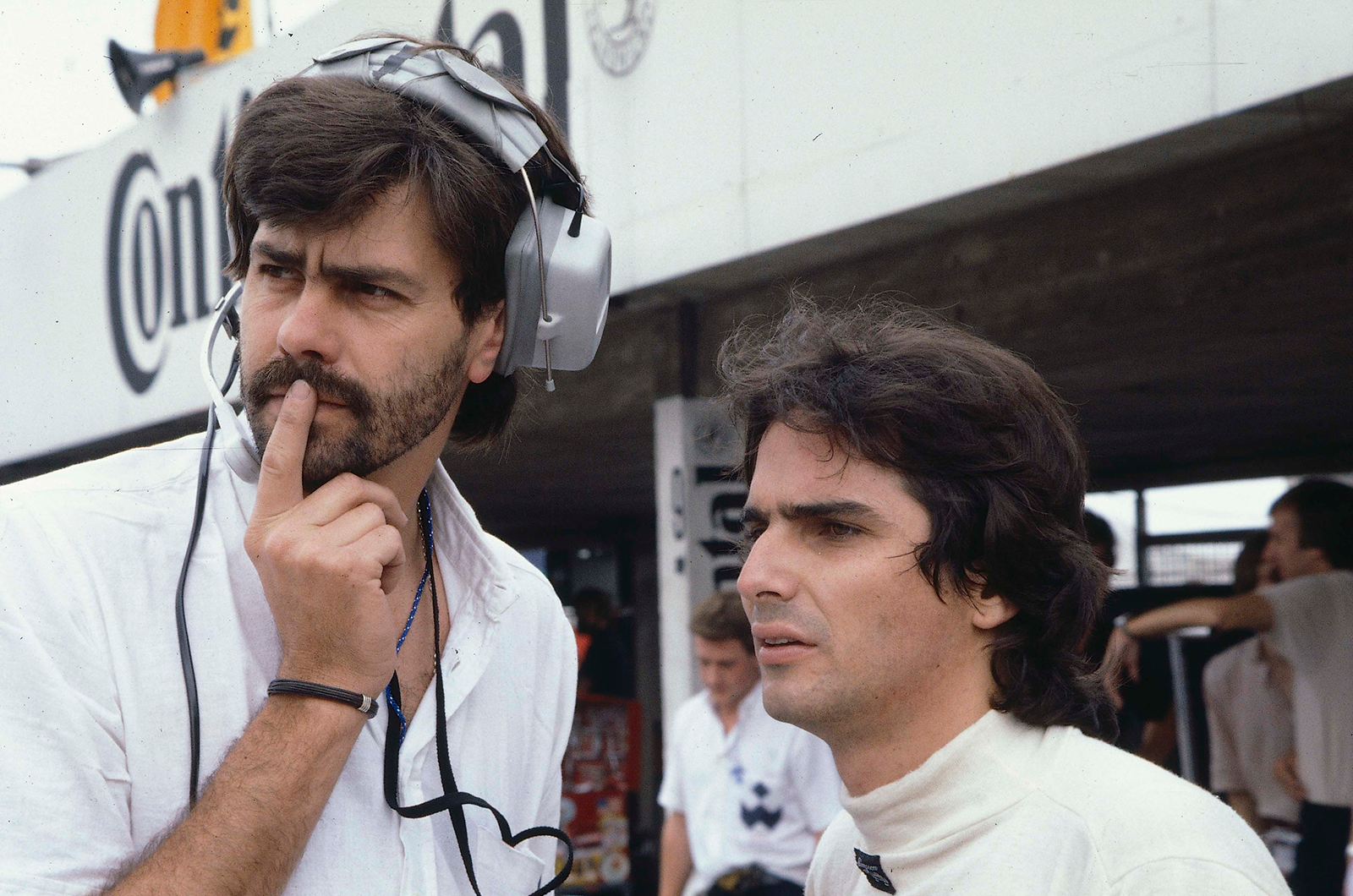

Lotus engineer Peter Wright and Colin Chapman were the architects of the ground-effect revolution

Perhaps not surprisingly, Formula One’s ground-effect revolution had started at Lotus.

At the end of the 1960s, teams had cottoned on to the benefits of wings – in other words, using the airflow over the top of the car to create downforce. As Colin Chapman later put it, during the following decade Lotus was the first team to also “harness the airflow underneath the car”.

The theory is simple: if you can shape the underside of a car in such a way to accelerate that airflow, you’ll create a low-pressure area. The car is therefore ‘sucked’ on to the road.