In the workshops at Neuilly-sur-Seine a flamboyant-looking cabriolet was created, the odd aesthetics trying to meld two eras with a defined rolling wing line matched to the all-enveloping main body and rectangular grille opening.

Saoutchik had to extend the main platform with outriggers, which resulted in an ungainly overhang around the wheelarches.

In contrast, Anderloni’s styling proposals at Touring created a stepped sill that wrapped under the body for a sleeker look.

Every Saoutchik body was handbuilt and no two designs were identical, with bespoke features usually incorporated.

Odd details included downturned doorhandles and various bumper designs, from individual overrider hoops, as here, to full-width body protection.

By then in his 70s, Jacques Saoutchik was leaving more responsibility to his son, Pierre. Aware of the firm’s outdated reputation, he had Philippe Charbonneaux and Paul Bracq produce a futuristic maquette of a streamlined coupé body for the second-series Z-102 that looked very like the Dual-Ghia.

The final result was more conventional, however, with a Jaguar XK-style pillarless roofline but with distinctive headlight pods, swept-back extended arches, side vents and – at last – flush doorhandles.

The best looking of all was the final BS2 coupé, which featured a lower, sleeker roofline. Pegaso would be Saoutchik’s last major contract – a year later the renowned coachbuilder closed its doors.

The most spectacular of the early Saoutchik-bodied BS1 Pegasos was chassis 126, which was a regular at concours events in France from 1953-’54 including Cannes and Deauville.

Finished in white with whitewall tyres, this showstopper featured a leopardskin interior and was often shown with a model in matching dress.

The first owner was Baron von Thyssen, the Swiss billionaire art collector. After the body eventually rotted away it became the basis for a replica of the ‘Rabassada’ spider race car.

One of the last Z-102s bodied by Saoutchik was a cabriolet based on a Series III platform. Finished in a cool Wedgewood-style blue, its unique body originally featured a low, speedboat-style ’screen with no frame top.

It was first shown at the 1954 Paris Salon and was later a star of the 1954 San Remo Concours d’Élegance, but eventually its first owner found the open body too flexible on rough local roads and had it converted into a coupé.

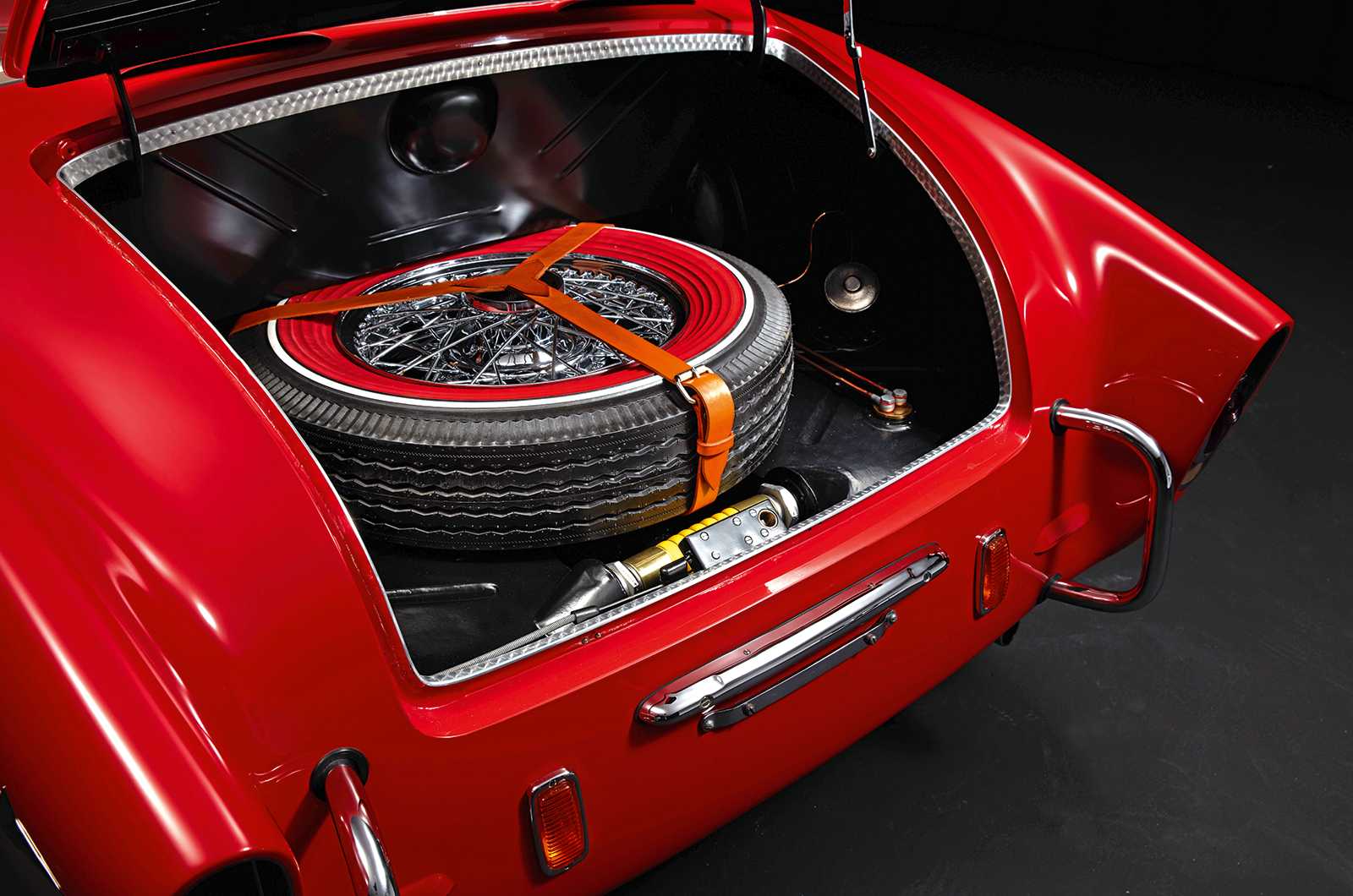

The Z-102B shown here, chassis 0146, was originally painted black with grey leather trim, and was also displayed at the 1954 Paris Salon in the Grand Palais, where local Jean-Claude Lamy was lured into purchasing it.

A keen enthusiast, he entered several competitions including the ’54 Rallye PanArmoricaine, and the following year’s Rallye Sablé-Solesmes.

Like so many European exotics, the Saoutchik coupé found its way to America where Don Rickert drove it around Alabama until May 1964, when it was sold to Bill Harrah, the gambling industry magnate who added the Pegaso to his ever-growing collection in Reno, Nevada.

Harrah kept the highly original Z-102B in his 1450-car museum until his death in 1978.

Holiday Inn took over the collection, which was greatly reduced through a series of auctions, and the Pegaso was acquired by Ralph Engelstad for the ImperialPalace Auto Collection in Las Vegas.

In 2017 the museum closed and the Pegaso was sold on and totally restored to Pebble Beach standards.

The Saoutchik bodywork was enhanced with a more glamorous two-tone paint scheme inspired by the Series BS2 Éspecial.

In February 2019, 76 years after its debut in the Grand Palais, the Saoutchik coupé returned to Paris for Rétromobile, where it was displayed on the stand of dealer Thomas Hamann.

Noble failures have a unique appeal. Created without a national legacy of performance cars, this handmade GT was clearly influenced by other cultures, but still has a strong Spanish character.

Had Ricart been less ambitious, Pegaso could have succeeded and La Sagrera might today be as hallowed as Maranello.

Images: Uwe Breitkopf

Thanks to Hamann Classic Cars, where the Pegaso is for sale

READ MORE

It’s a Jaguar XK120 – but not as you know it

Open for business: Maserati A6GCS by Frua

Praho: the unique Alfa Romeo you might never have heard of

Mick Walsh

Mick Walsh is Classic & Sports Car’s International Editor