Ian Davis and panelbeater/sprayer Adrian Neale excelled themselves with the body.

The coachlines on the flanks were applied freehand by signwriters, with matching beauty lines on the hubcaps.

These were done, logically enough, on a potter’s wheel initially, then by hand when that method didn’t prove accurate enough.

“He only wanted to charge £80,” says Rees, “but for the time and skill he put in I insisted on giving him a much more appropriate amount.”

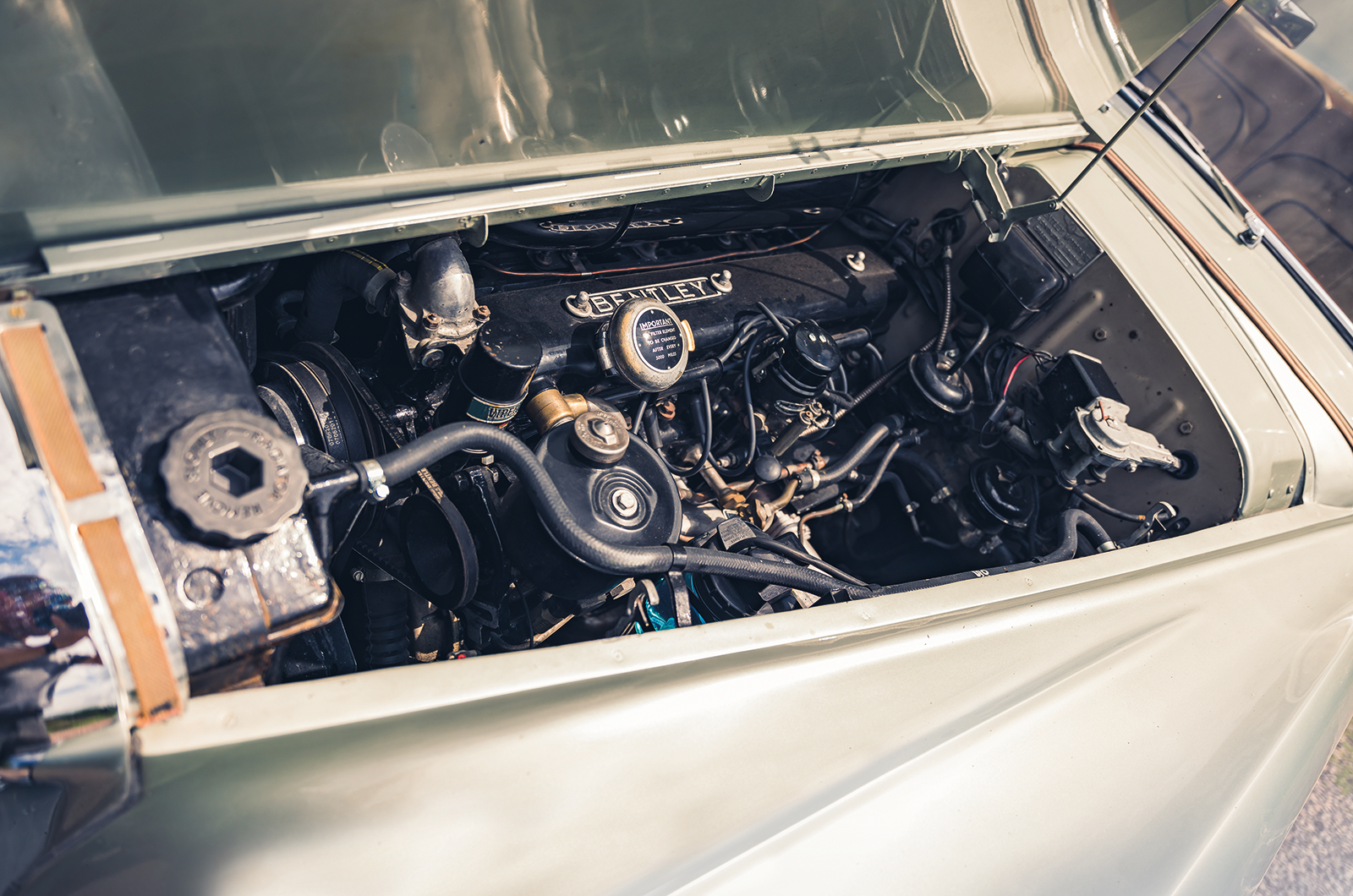

The Bentley’s fettled ‘six’

Getting the engine running was no real problem.

Retired 79-year-old master mechanic Alun Davis – father of painter Ian – tuned it by ear, and was so chuffed to be working on such a beautiful piece of machinery that he wouldn’t take any money – so Warrender bought him the finest malt whisky he could find.

As light began to appear at the end of the tunnel, more information about the history of the Bentley started to emerge.

This Bentley is a car with a great deal of history behind it – this sticker is testament to its time spent in the US

The original buyer, Victor Ercolani, made himself a pile of money producing television cabinets.

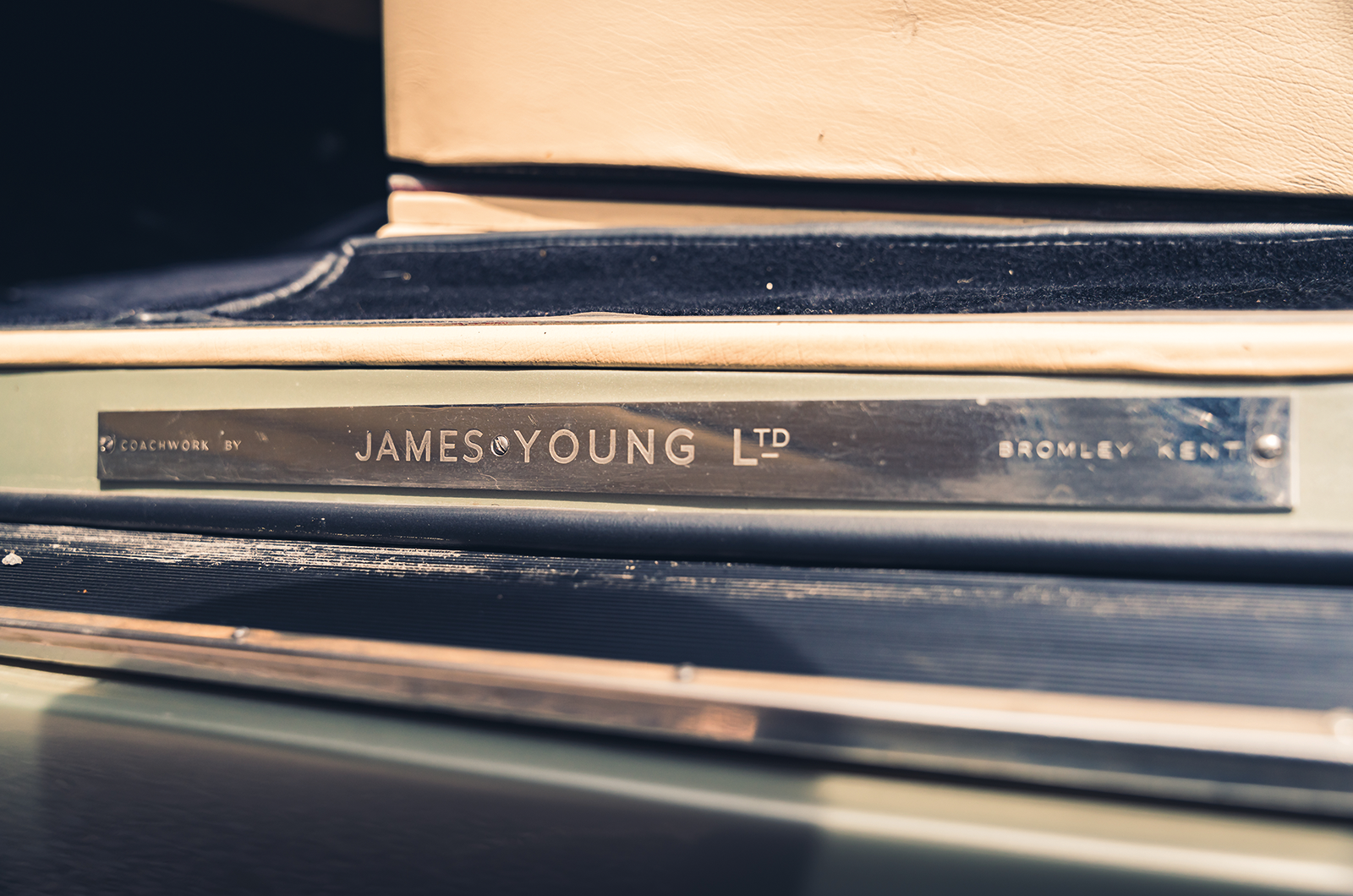

A scion of the famous furniture-making family, Ercolani had a preference for James Young bodywork and presumably had no trouble finding the £8000 required to buy the Continental.

At some point his wife reputedly suffered some kind of life-changing injuries while riding in the Bentley: there was evidence of some very well-repaired damage on one front wing to corroborate this.

The mileage was supported by contacting the dealer whose sticker was still in the rear window. He serviced the James Young for the Ecrolanis and confirmed that they rarely used it.

Marchal parking lights show the Bentley has also lived in France

At the time it wore Victor’s private number, VE25, which is now on a modern Mercedes.

It was also established that at some point the S1 lived in France – hence the Marchal parking lights – and was one of the many Rolls-Royce and Bentley models exported to America in the early ’70s, when the weakness of sterling against the dollar made such cars look temptingly inexpensive.

The elegance of the £2500-cheaper Standard Steel S-types and Silver Clouds probably contributed to the demise of coachbuilt models such as the James Young Continentals as much as the technical challenges of monocoque construction.

Even so, this Bentley is a leaner-looking car in the metal than any factory body.

Rear head- and legroom are at a premium in this Bentley

Inside, the dash – refurbished with the help of Michael’s Wood Restoration in Brighton – sweeps elegantly into the door cappings, with delicate figuring of the gleaming walnut and instruments behind the steering column for a more rakish feel.

The column itself was bespoke, 2in shorter, for the not notably tall Ercolani.

The seats recline and are surprisingly slim, but there is still not much head- or legroom in the rear.

As in the Mulliner Flying Spurs, the dinky rear doors make elegant ingress and exit tricky.

“It accelerates briskly, with a remote hiss of discreet power”

This car has the later combination of an 8.2:1 compression engine with 2in SU carburettors.

Warrender prefers the simplicity of this 4.9-litre, c180bhp straight-six to the later V8s, which are thirstier and marginally less refined in some ways.

It accelerates briskly, with a remote hiss of discreet power and only a suggestion of slur between third and top in the automatic gearbox.

There was no particular attempt to make the Continental radically lighter than the Standard Steels, so extra speed comes by way of a higher compression ratio and less frontal area.

“You can control its bulk with surprising delicacy through the power steering”

Hills are irrelevant, and it throttles down to 800rpm in top.

Massive and powerful, the twin-master cylinder, twin-front-circuit drum brakes will put this hefty, rather firm-riding car on its nose when asked, and you can control its bulk with surprising delicacy through the power steering, which really does just assist rather than take over.

Warrender reckons he can get 20mpg from his S1 fastback; the James Young returns a touch less, but is still very usable and driveable with a tight, rattle-free feel.

Complemented by 20kg of modern soundproofing, the quality of that much-agonised-over sound system is exquisite.

A delighted Warrender with the finished Continental, nearly a decade after he began taking it apart

Tenacity and attention to detail were the routes to success in this job, which was finished in a remarkable 10 months.

“You could never say ‘that will do’ because James Young’s craftsmen would never have said that,” says Rees, who admits to some eerie feelings while building the car.

“I could occasionally feel a sort of guiding hand, almost as if those craftsmen were willing the Bentley back to life.

“Such as when I realised I was short of a unique fixing for the front wing, one I had never seen in the 4500 nuts, bolts and screws I’d already sorted: somehow, I found it immediately in the first box I opened.”

Rees is satisfied that the S1 is now as close to a new car as possible, as tight as if it had just left the factory yesterday: “Working with Ernie was a joy, and I must have done something right because I’ve now got three years’ work ahead of me doing his AC Ace and S1 fastback!”

Images: Max Edleston

James Young Coachbuilders, 1863-1968

Like most of the great names, James Young of Bromley started out building bodies for horse-drawn vehicles.

On merging with Gurney Nutting as part of the Jack Barclay group in 1937 the firm was exclusively aligned with Rolls-Royce, although it had already bodied a variety of exotic Continental makes: for a while it was the official Alfa Romeo coachbuilder for the UK market.

It was an innovative firm pre-war, listing firsts such as a headliner that reduced drumming and a sliding-door patent that was later sold to VW for its vans.

It was the last official independent coachbuilder for Royce and Bentley chassis and, with 120 staff making 60 bodies a year, was second only to HJ Mulliner in producing bespoke MkVIs and R-types in the 1940s and ’50s.

James Young flourished in the 1940s and ’50s, before a slow decline in the following decade

Having achieved a peak of elegance with its 1959-on Phantom V Touring Limousines, in the ’60s the firm struggled to adapt to monocoque technology. It also lost the light touch and feel for proportion of gifted stylist AF McNeil.

The firm disappeared with a whimper in 1968, with a plain-Jane interpretation on the two-door Silver Shadow/T1 theme, of which just 50 were sold.

A decade earlier, the launch of the S-type Continental resulted in a flourish of creativity. Where R-types had been the preserve of HJM and Park Ward, for the S-type official sanction was given to a James Young four-door.

Design number CT29 was a handsome four-light shape first seen in 1957 and built to the tune of 16 cars.

There were a further four two-doors, and in both cases they are similar to the Mulliner Flying Spurs: the only real giveaways are the unbroken swage line and JY’s famous square door buttons.

Most HJM S1 Flying Spurs were six-lights, and when the S2 was introduced James Young followed suit.

It built a further 61 four-doors (and a handful of Silver Clouds with the same body) through to the demise of the S3 in 1966.

Factfile

Bentley S1 Continental James Young four-door

- Sold/number built 1957-’59/16

- Construction steel chassis, aluminium body

- Engine iron-block, alloy-head, ohv 4887cc ‘F-head’ straight-six, twin SU carbs

- Max power not disclosed

- Max torque not disclosed

- Transmission four-speed automatic, RWD

- Suspension at front independent, by wishbones, coil springs, anti-roll bar rear live axle, semi-elliptic leaf springs; telescopic dampers f/r

- Steering power-assisted cam and roller

- Brakes drums, with gearbox-driven servo

- Length 17ft 8in (5385mm)

- Width 6ft 1in (1854mm)

- Height 5ft 1in (1549mm)

- Wheelbase 10ft 3in (3124mm)

- Weight 4500Ib (2041kg)

- 0-60mph 10.6 secs

- Top speed 115mph

- Mpg 14

- Price new £7913

- Price now £300,000*

*Price correct at date of original publication

READ MORE

The story of Bentley: from Blowers to Speed 8 and beyond

Attention to detail: Ferrari 328GTB restoration

How the other half lived: Bentley MkVI vs Armstrong Siddeley Sapphire 346

Buyer’s guide: Daimler Majestic

Martin Buckley

Senior Contributor, Classic & Sports Car