North Londoners of Italian extraction – Ruggeri runs a travel business, Bragoli a car-detailing outfit – they perfectly embody the enthusiasm these Suds generate.

“I had known about the 1977 ti for a couple of years,” says Ruggeri, “and begged the owner to let me buy it. He only caved when he needed a deposit for a modern Alfa, so I had it as a Christmas present to myself in 2012.

“I was so chuffed I kept it outside for a week so I could look at it through the curtains every 10 minutes.”

“What strikes you about all three is how modern and capable they feel”

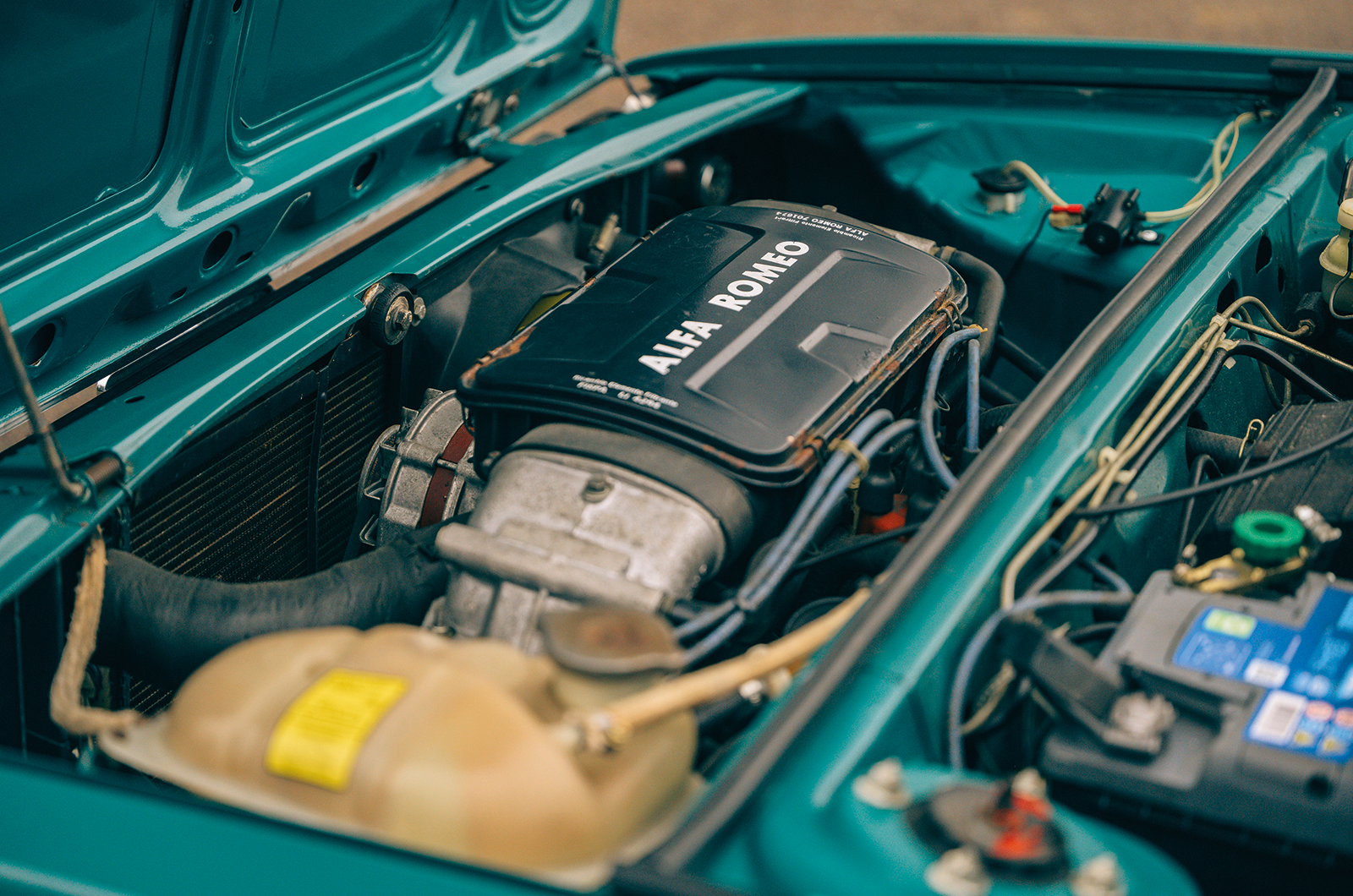

His green twin-carburettor Sprint Veloce came from a dealer in Kent in 2014. Also from the pen of Giugiaro, these lower-slung, chisel-edged coupés first appeared in 1976 and were five-speeders from the beginning, with a hatchback but without folding seats.

This 1980 example doesn’t get used as much because it is not quite so comfortable to drive as the ti; but we will come to that later.

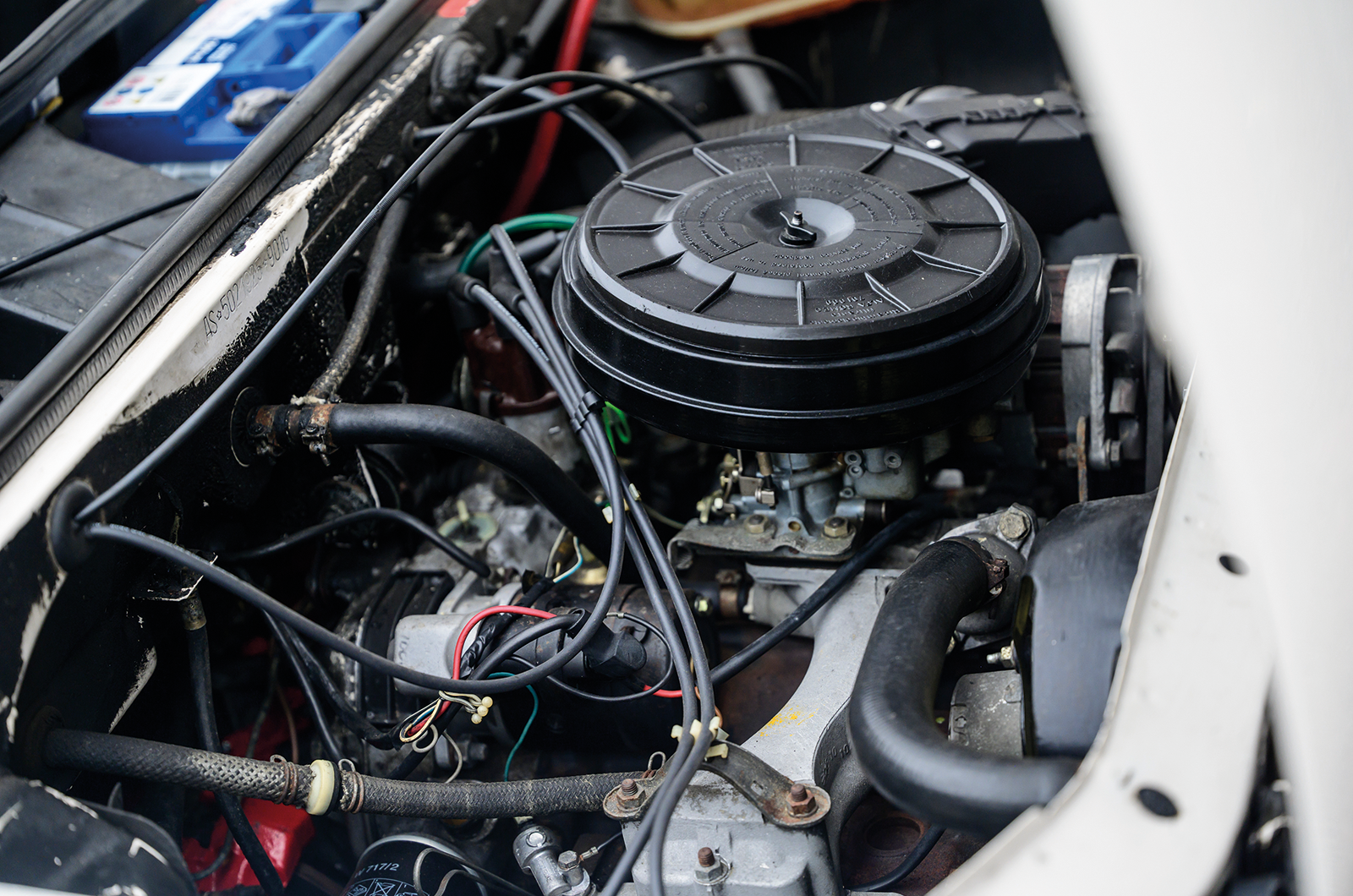

In the early Sud saloons you didn’t get carpets, a heated rear window, a brake servo or a rev counter as standard, but the ti and Sprint upped the game.

Owners enjoyed cloth trim, extra gauges (rather than warning lights) and sports road wheels to go with the tail and chin spoilers.

Clockwise from top: these are true driver’s cars; Campagnolo alloys for the Coupé; attractive four-stud steels on this ti

“That Alfatex interior is irreplaceable,” says Ruggeri, looking fondly at the near-immaculate cabin of his ti.

“Generally speaking, Suds are not so well served for parts as the 105s, although they are getting better – maybe because more cars are being restored now.”

You can’t talk about Alfasuds for long before the subject of the dreaded brown cancer comes up.

Prior to delivery they needed paint repairs and most Suds had new sills fitted at their first MoT unless, as with these cars, they were protected by Ziebart from new.

It was not an issue with the quality of the steel, reckons Ruggeri, but rather the poor working practices at Pomigliano d’Arco.

Raw shells would end up being stored outside or left to gather condensation while strikes and walk-outs were resolved. Towards the end of the 1970s things did improve, and it is a fact that the post-1980 Suds – Series 3s, picked out by their big bumpers – are better-built cars.

Vital Ziebart sealant on this example

Bragoli’s award-winning ti is one of the short-lived Series 2s, built only between May 1978 and January 1980, with a 75bhp engine from the first of the Sprint coupés.

He bought it in response to a rather brusque ‘take it or leave it’ website advert in 2016: “It had been sitting in a garage since 1991 – I’m only the fourth owner – and was rust-free, although we bare-metalled it because it was so original it was worth doing properly.”

Bragoli, 28, was brought up onItalian cars and his Sud shares garage space with a low-mileage original Fiat 500 and a Strada Abarth 130TC.

This white Series 2 ti is an award-winner

What strikes you about all three Suds is how modern and capable they feel. This really was a new chapter opening in terms of people’s expectations.

Today some would consider the steering on the heavy side at low speeds, but it isn’t really. Assistance has made us all soft.

And what counts, in any case, is the way the lack of understeer, body roll and tyre squeal gives them such a planted feel, with margins of grip you would never begin to explore on the road.

The Suds are so biddable and confident that to drive them quickly becomes a sort of relaxation. The steering never fights you, never loads up, and the brakes are strong, if a shade over-boosted.

The later green Sprint coupé combines a baby GTV6 look with its Sud styling of Series 1 (red, rear) and 2 (white, front)

The Sprint Veloce, with its twin carburettors and 1490cc, is the liveliest of the trio – as much in torque as outright pull through the gears.

But all three feel vivaciously eager. From a slightly throbbing tickover to a free-spinning 6000rpm and beyond, there is something refined yet unburstable about the way these little engines sing through the revs.

The tis have slightly offset pedals, which you soon get used to, but there is a slight sense that the steering wheel is sitting in your lap in the Sprint. It feels more cramped and you have to concentrate if you are not going to get your feet tied up in the closely grouped pedals.

“The coupé is a nightmare to drive,” agrees Bragoli, “in the saloon you feel instantly at home.”

The Sprint’s cabin is comparatively claustrophobic

I’m not usually sensitive to driving positions but it cannot be denied that the ti is a much nicer place to be, and not so austere and cheaply appointed as the contemporary reports suggest.

I like the way Alfa put all the controls on column stalks, even the heater blower, and the good all-round vision was part of Hruska’s brief.

Agility and cornering power do not come at the expense of comfort, either: the ride is supple enough to shrug off potholes and all but the most aggressive of traffic-calming measures.

The Series 2 ti has a throaty exhaust rasp and feels appreciably but not dramatically stronger through its five speeds, in a gearbox that plots a notably slick and precise course.

It has a strong synchromesh and works well with the Sud’s eager throttle response. This must have been one of the first really nice gearboxes in a front-drive car in those pre-Alfetta years, when an Alfa with a rubbish gearchange was unthinkable.

Its owner finds the green Sprint coupé less comfortable to drive

Sharing nothing with its rear-drive, twin-cam-engined Alfa Nord predecessors, there was a touch of genius about this little saloon from the start that no subsequent Alfa Romeo has managed to recapture.

The mystique fully lived up to the marque’s reputation as a maker of great drivers’ cars, perhaps even enhanced it.

A total production of 1.1 million makes these the biggest-selling Alfas of all, and projected sales were doublethat.

Yet the Sud has become a tragic shorthand for the epic rust problems and shoddy build quality that dogs perceptions of every Alfa Romeo to this day. And perhaps even Italian cars generally.

The Alfasud sold well and remains a popular classic car today

The sad part is that good Alfasuds, or even bad ones, are incredibly hard to find.

Fewer than 80 are currently accounted for on UK roads. Like white dog poo, you just don’t see them any more.

Yet there is something about these cars, beyond mere rarity, that still makes grown men such as Bragoli and Ruggeri weak at the knees.

Somehow the strife, political machinations and sense of missed opportunity that surround this flawed prodigy of a car only add to the romance.

Images: Olgun Kordal

Thanks to Keith Waite; Bragoli Cars

READ MORE

Flawed diamond: Alfa Romeo Montreal

Buyer’s guide: Alfa Romeo Alfasud

Future classic: Toyota GR Yaris

Martin Buckley

Senior Contributor, Classic & Sports Car