With its sharp throttle response the Triumph feels lively in its notchy-shifting lower gears, squatting down and growling hard towards 4000rpm, revs that will maintain 100mph in overdrive quite peacefully with surprisingly little road noise.

The Range Rover would be maxed out at that speed, even with the optional Fairey or GKN overdrive, but the security of its on-road handling has an edge over the faster Triumph.

Certainly the high build tends to exaggerate the body roll but, once you grow accustomed to this, the all-wheel drive means it hangs on tenaciously, with smoke coming off the front tyres if you are really trying on a slow, tight bend.

The power steering is not the last word in feel, but neither is it over-boosted. Unhappy memories of driving an early Rangie without PAS would make it non-negotiable for me.

The Range Rover has brakes that rarely cross your mind; likewise in the 2.5 PI.

Cornering ambitiously, the Triumph has much more conventional limits and is one of those cars that probably corners well (which it does) despite its feel-free power steering negating the benefits of its rack-and-pinion mechanism and a respectable three turns from lock to lock.

There’s a lot you can do to sort these big Triumphs but, as standard, it rolls quite a bit, betraying its ’60s origins.

You learn to trust in the safely understeering PI’s ability to hang on; it feels as though it would be good fun in the wet.

These oddly complementary British Leyland products were early-’70s ‘lifestyle’ cars that competed for the attentions of well-heeled buyers who required utility that was not utilitarian, status without ostentation.

Darling of the middle classes, the handsome Triumph Estate almost had the field to itself for five years and, in MkII PI form, had reached the peak of its development curve.

The Range Rover, in many ways the car that took over from the Triumph Estate as the horse trailer-pulling town-and-country machine of choice, was just getting started by that stage.

Not even its hopeful parents could have guessed at what was in store for it, and the rest of the British motor industry, in the five decades that have followed since it was introduced.

Images: James Mann

Thanks to The Triumph 2000, 2500, 2.5 Register; Bishop’s Heritage

Factfile

Range Rover

- Sold/no built 1970-’88/96,331 (to end of ’81)

- Construction box-section chassis, steel and aluminium body

- Engine all-alloy, ohv 3528cc V8, twin Zenith-Stromberg carburettors

- Max power 135bhp @ 4750rpm

- Max torque 205Ib ft @ 3000rpm

- Transmission four-speed manual, high and low range, 4WD

- Suspension: front Panhard rod rear A-bracket, self-levelling struts; live axle, coil springs, radius arms f/r

- Steering recirculating ball, optional power assistance

- Brakes discs

- Length 14ft 8in (4470mm)

- Width 5ft 9in (1778mm)

- Height 5ft 10in (1778mm)

- Wheelbase 8ft 3in (2540mm)

- Weight 3800Ib (1724kg)

- Mpg 14

- 0-60mph 13.9 secs

- Top speed 95mph

- Price new £1998

- Price now £12-30,000*

Triumph 2.5 PI Estate

- Sold/number built 1969-’75/4102 (MkII Estates)

- Construction steel monocoque

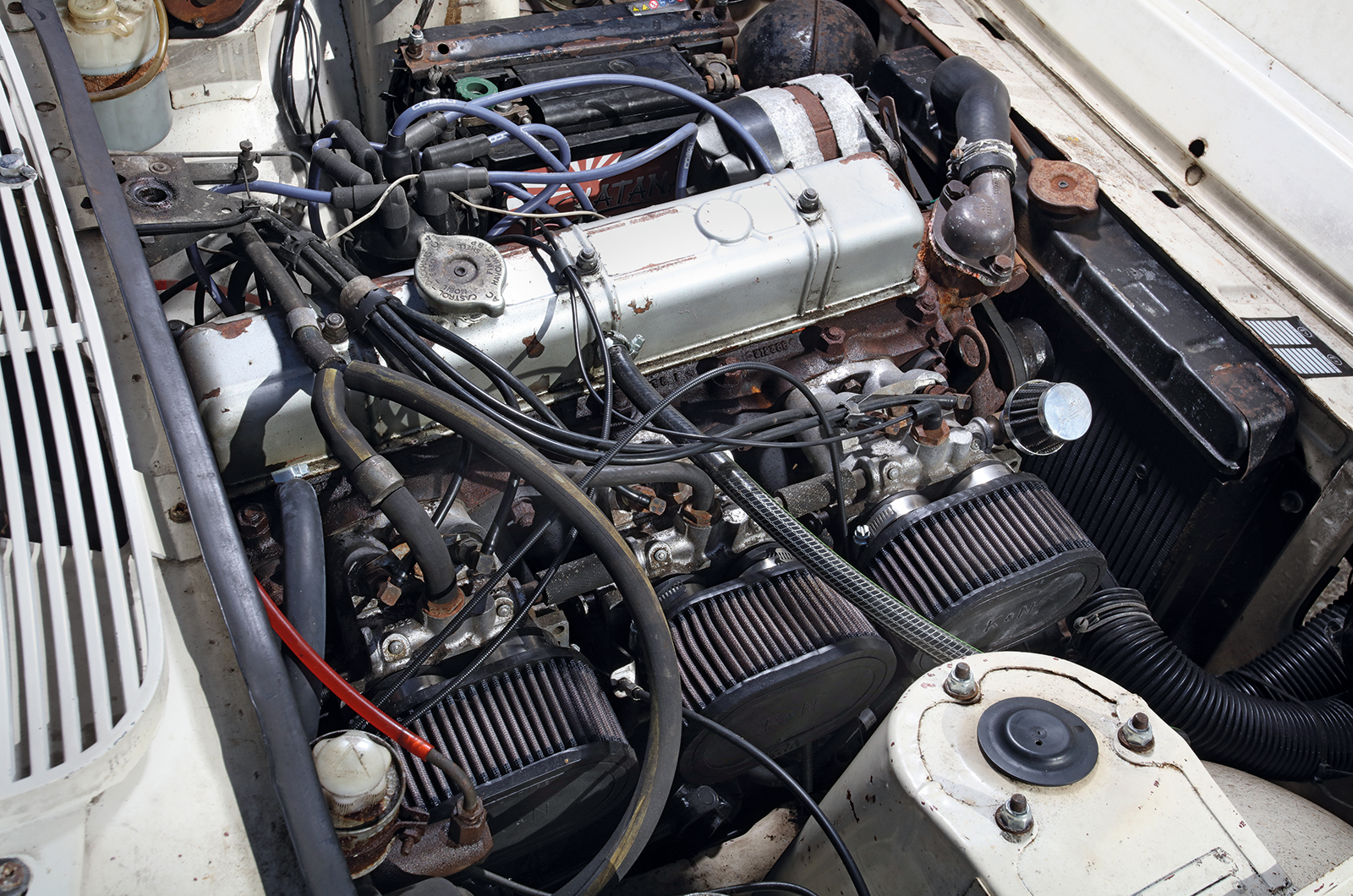

- Engine all-iron, ohv 2498cc straight-six, with Lucas mechanical fuel injection

- Max power 132bhp @ 5450rpm

- Max torque 153Ib ft @ 2000rpm

- Transmission four-speed manual, overdrive on third and fourth, RWD

- Suspension independent, at front by MacPherson struts rear semi-trailing arms, coil springs, telescopic dampers

- Steering power-assisted rack and pinion

- Brakes discs front, drums rear

- Length 15ft 2in (4629mm)

- Width 5ft 5in (1651mm)

- Height 4ft 8in (1422mm)

- Wheelbase 8ft 10in (2692mm)

- Weight 2701Ib (1225kg)

- Mpg 22

- 0-60mph 9.2 secs

- Top speed 110mph

- Price new £1869

- Price now £8-10,000*

*Prices correct at date of publication

READ MORE

Luxury on the farm: Range Rover vs Mercedes G-Wagen

Separated at birth: Saab 99 vs Triumph Dolomite

Why the Jaguar XJ is the world’s best saloon car

Martin Buckley

Senior Contributor, Classic & Sports Car